Five big things we learned at the Brave New Work Conference

Conference summaryPPF’s inaugural Brave New Work Conference brought together more than 200 top thinkers, doers and deciders in Toronto on June 26 to discuss how business, labour, higher education, government and new disruptors can shape future-ready policy pathways.

Five major themes emerged:

- Despite low unemployment, people worry what the future of work will mean for them and society

- Education and employment support systems urgently require reform

- The lack of workplace diversity in the past is hampering the future of work

- Power imbalance in the workplace is a bigger factor than technological change

- We need all hands on deck to confront the challenges ahead

We’ve summarized the five takeaways here. You can get the full picture by watching any or all the speakers and sessions.

1. Despite low unemployment and labour market shortages, people worry what the future of work will mean for them and, even more so, their community and society at large.

New technology can drive opportunity and optimism, but it can also be disruptive, scary and uncomfortable when we perceive it to be affecting our work and quality of life. The conventional view—that changes in work and technology are happening rapidly— holds true. Indeed, a highlight of the conference was an in-depth look into the changes in the automotive industry that have led to real-life disruption nearby, as the General Motors plant in Oshawa, Ontario imminently moves away from vehicle assembly.

We also heard there is a significant and growing skills gap among mid-career professionals, who may be less adaptable to the new economy and who hold substantial financial responsibilities for their dependents. Research from TD Bank suggests future financial security is a worry for almost 80% of Canadians. In 2017, almost 40% of adult Canadians said they had experienced moderate to high levels of income volatility over the previous year.

The possibility of job losses from automation and the increasing use of artificial intelligence in the workplace is viewed negatively by many Canadians. New research commissioned by PPF from University of Toronto Professor Peter Loewen found that those people most anxious about job loss are more likely to hold populist and nativist beliefs. People also worry that the rise of artificial intelligence and automation in the workplace will reduce social mobility and increase current inequalities. The good news is that despite their attraction to populist and nativist arguments, what they really want are for elected officials to address their work anxieties by adopting non-radical policy choices. Their preferred solutions were incentives for employers to offer more training, support for more STEM education and help for older workers to adjust.

However, we also heard contrarian—and more positive—views of the future of jobs and workplace relations.

While changes in work and technology are occurring, Jim Stanford told us, there will continue to be jobs for people in the future, recognizing that people have a unique skill set which cannot be replaced by machines.

John Hagel told us that the key for people in the future of work will be to use uniquely human skills and abilities to our advantage; automation and artificial intelligence cannot address unseen problems and opportunities in the workplace or create new ways of dealing with old problems.

We heard from Jim Stanford and Wendy Cukier that, contrary to popular reports, the uptake of labour-saving technology in the workplace is not accelerating because businesses, so far, are not investing in new technologies at the rate previously imagined (though this could prove to have been a technology adoption curve effect). The populist view that most jobs are at risk from automation and artificial intelligence might be true, but we may have been wrong about the timing of the impact. Fears about automation do not match the observed economy-wide reality.

The unpredictability of the future of work meant that the policy suggestions were broad and diverse. Policy solutions discussed at the conference included:

- We need to better understand, quantify and measure the changes to the workforce as a result of implementing new technologies and adopting automation and artificial technologies in the workplace. Without this, policy solutions will be hard to scale and implement successfully.

- Governments have a role in planning for the future of work and reducing anxiety in the population, ensuring that individuals’ expectations of the job loss effects of automation and AI are aligned with their actual exposure to job disruption.

- Both short- and long-term views are needed. While policy solutions that recognize automation and AI’s short-term disruptions are important, solutions must also address the longer-term effects on social and economic structures

2. Education and employment support systems urgently require reform to address growing demand for mid-career skills, upgrading and job shifting.

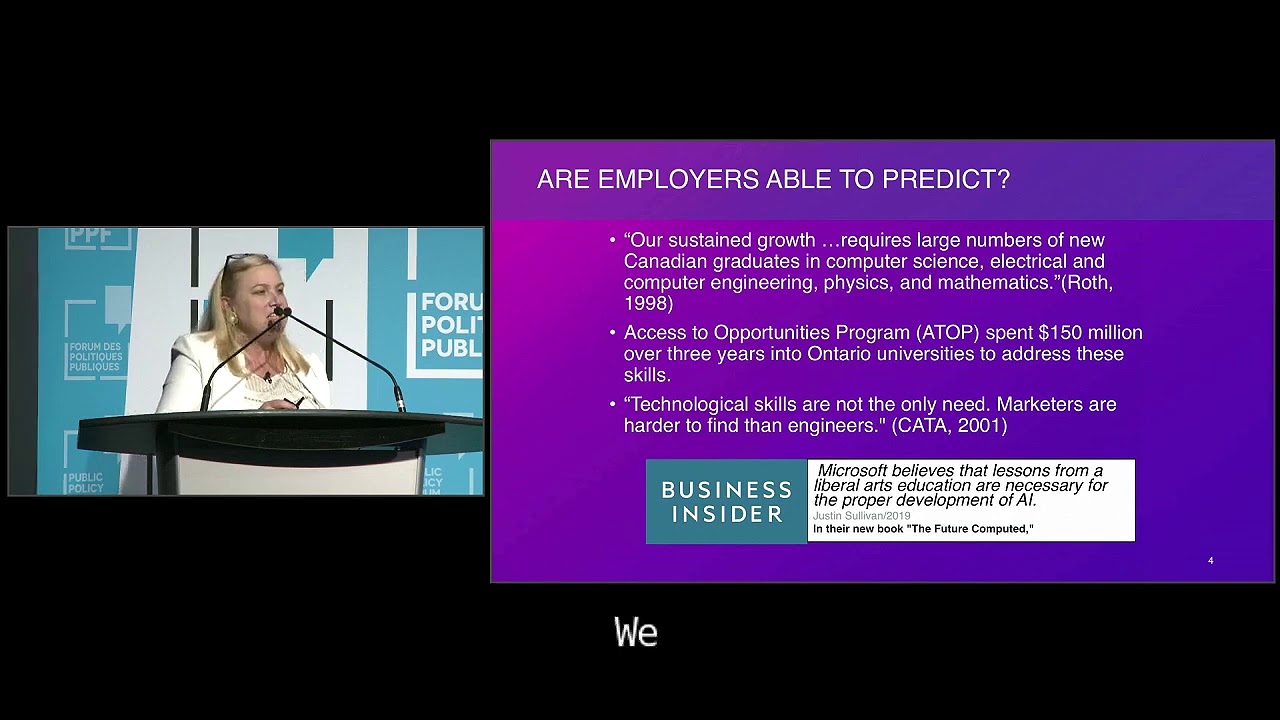

Education and higher learning institutions were naturally at the centre of conversations during the conference. Some speakers, such as John Hagel and Tom Roemer, argued that our education system lacks sufficient flexibility, often as a result of regulation. The trades were highlighted as an example of the flexibility of education being contradicted by the requirements of accreditation bodies. To ensure a common standard of graduates across a course, each training institute brings training down to a common level and potentially a minimal level of investment.

Canada has previously catered well to learners in structured educational institutes, with provincial employment centres helping those out of work get training, build skills or find a job. In employment services, Gladys Okine told us that Canada has well-organized set of services in employment, but they are not always innovative.

There is a gap and opportunity in Canada to cater for the individuals who are already working but are at risk of disruption as a result of automation and artificial intelligence. We need a system to provide career guidance, high-quality labour market information and training to Canadians in “the messy middle” before they are disrupted, unemployed or need to change careers.

Policy options discussed at the conference included:

- Employment guidance is a benefit for those from all walks of life, not just when it is desperately needed. Innovative “stackable” approaches to learning, which could be employer-paid and flexible enough for people to come in and out of training as they need, might be necessary in the future.

- We must fundamentally reform the educational curriculum starting at pre-school to focus on capabilities rather than just core skills.

- Successful collaboration between institutions and employers is one way to structure “the messy middle”. Uber told us they had successfully partnered with higher education institutions to provide workers with an opportunity to learn and develop. In Oshawa, the General Motors plant closure resulted in an innovative collaboration across the community, General Motors, local business and Durham College to transition, coach, and get workers ready for new careers outside the assembly plant.

- The Anishinabek Nation told us about their own higher education learning institute which develops people to meet social needs like nursing and childcare. Here, education is holistic, it is not just professional training. In Ontario, the Indigenous Institutes Act 2017 allows Indigenous institutes to be more agile. There is a lot of flexibility to design training within this learning institute, which can match the needs of employers and the future of work.

3. A lack of diversity in the history of work is re-asserting itself in the future of work.

A common theme of the conference was the lack of diversity of voices among those creating, designing and planning the future of work in the fields of technology and computer science. Rachel Wernick told us that our analysis of the future of work is still structured around hidden gender and ethnicity defaults, hindering how we assess the future of work. Paid work, gig-work, and warehouse automation examples in future of work research are focused on the male experience, neglecting the broader diversity of experiences in unpaid work, direct or online selling, or in retail.

There is still a lack of diversity of voices at the table. Women are underrepresented in technology and computer science, where the technologies of the future are being designed. Underrepresentation of women and people from diverse backgrounds in roles where technology is developed, and in the corporate pipeline, means these voices will be underrepresented in the future of work.

The risk of job disruption through automation tends to disproportionately impact workers who are already marginalized and face challenges participating in the workforce. Research shows automation of jobs affects lower income work, those with longer commutes, and those with language barriers. Pre-existing barriers can also make it challenging for workers to participate in retraining programs, increasing the already large disparity in outcomes.

Some of the policy solutions suggested under this theme were relevant not only for the future of work, but for broader public policy:

- We need to always be conscious of uncovering the hidden default in policymaking. We cannot continue to perpetuate the inequalities and lack of inclusiveness that exist in the economy that we have today.

- Ensuring the diversity of those who create and plan the use of future technologies is vitally important in creating an equitable future of work.

4. Work isn’t going away. Power imbalances in the workplace is an equal or an even bigger determinant than technological change and need to be at the forefront of the future of work policy debate.

One of the key policy debates at the conference was how to manage and regulate power in the workplace. The changing nature of the relationship between employers and workers is a constant theme in the future of work debate.

For the worker, employment provides security and benefits. But the weakened bargaining power of workers means fewer benefits and fewer pensions. Automation in the workplace is not necessarily a bad thing as long as those who are displaced have something else productive to do with their skills and abilities. But in a standard profit-driven employment relationship, a worker’s skills and abilities may not be redeployed, making work insecure.

The skills shortage debate can also be viewed through the lens of a changing power dynamic. While there are current labour shortages, such as in truck driving, Canada has a more skilled and educated workforce than it ever has had before. We should question the employer-driven narrative of the skills shortage; are employers offering the rights terms and wages for the jobs they offer?

Conversations about the future of work need to focus on the power imbalances and structures in place. How will the future of work be organized, compensated and set up to protect employees? Stronger, rules-based labour market policies are needed to ensure productivity gains are shared across labour and capital. What limits can we place on insecure, precarious work so people can still have decent work and earn good wages? The modernization of labour laws has a part to play in this discussion.

Immediate policy solutions offered to address power in the structure of work focused around the social safety net and ensuring benefits and pensions continue to be equitable:

- We need to modernize the social safety net to focus on the employee, rather than on the employer. Portable benefits are often mooted as one solution, but other worker-centric options are possible. There are ways in which the traditional protections and standards of the labour market could be adapted and modernized to fit a more flexible and free-ranging labour market.

- We should protect the quality of jobs and support stronger labour conditions to force employers to increase the compensation and the skills opportunities they provide to their workers.

- Regulatory structures and active policies should support wages and lift them over time, empowering workers to give them information and the capacity to bargain over technological change.

- Skills and retraining have been a key area of discussion in the future of work, but we should also focus on making people’s lives better, not on just ensuring they have a job.

5. We need all hands on deck.

While the future of work is a hot topic, we also need to be thinking about today’s issues in the workforce. Current endemic labour shortages in healthcare, truck driving and other core industries also need policy solutions.

Armine Yalnizyan told us that, in the next 20 years, we are going to need all hands on deck as the Canadian population ages and retires, and as technology plays a larger role in workplaces. Employers can’t leave this to governments and governments can’t leave it to employers. And both must be engaged with educators. Nor can unions be left out. Individuals need good information with which to guide their careers. Investing in improving students’ capacity to learn will not be a wasted effort. We cannot exclude the 10-15% of Canadians, who are not traditionally getting the education they need, from fully participating in the future of work. Falling through the cracks of the education or social welfare system can no longer happen.

The conference highlighted many positive public policy collaboration efforts across the public, private, and not-for-profit sectors. Such collaboration is essential to prepare Canadians for the future of work. No one is set up to do this alone.

Thank you to our lead sponsor:

Thank you to supporting partners: