Precarious Employment to Stable Flexibility: What do Canadian Gig Workers want?

Brave New Work Blog SeriesRead Part One in this two-part series by Peter Loewen and Blake Lee-Whiting.

Introduction

Gig work is becoming increasingly prevalent in Canada as platform economy technological disruption sweeps north. Gig work can allow workers the flexibility required to pursue other responsibilities, such as family obligations or educational pursuits, but this type of work often becomes a substitute for more secure employment. In response to this inherent precarity, what protections and employment policies do gig workers favour?

This blog post briefly examines the nature of gig work in Canada by exploring who gig workers are, why they choose to pursue gig work, how they perceive their own social status and the policies they prefer. Our work suggests that:

- Gig workers favour government policy that will increase the amount of workplace protections for them, including paid breaks, the right to unionize and recourse for wrongful dismissal;

- Half of gig workers surveyed in Canada indicate they prefer gig work because of the flexibility it offers;

- Across the board, gig workers are overwhelmingly in favour of government action to stabilize gig work.

Precarious work

On May 11, 2020, Foodora, a food-delivery brand owned by German multinational online food-delivery giant Delivery Hero, closed its operations in Canada, citing “strong competition in the Canadian market… We’ve been unable to get to a position which would allow us to continue to operate without having to continually absorb losses.” Considering this decision occurred right as the COVID-19 pandemic’s first wave was sweeping Canada, thereby increasing demand for at-home food delivery, some critics, including the Canadian Union of Postal Workers, argued Foodora was instead circumventing successful attempts by its gig workers to unionize.

Regardless of why Foodora chose to leave Canada, the outcome to its contract workers was clear: hundreds lost employment during the pandemic with unclear access to government benefits, such as CERB, which require a record of employment. After a mass-unemployment event, government usually elects to take steps to mitigate the negative economic and societal ramifications of hundreds of suddenly unemployed people. The Rapid Re-employment Training Service operated by the Ontario government, for instance, automatically creates a “response team for layoffs affecting more than 50 people.” Yet, there has not been similar action taken by government to address gig-work unemployment events.

The gig economy presents unique challenges that may not be well addressed by existing government policy. Considering the multitude of response options available, what do gig workers want from government? Is there an opportunity for government to innovate new policy approaches specifically targeted towards gig workers?

To better understand the policy preferences of gig workers, we conducted a survey of 121 people in Canada who receive income from gig working. We recruited respondents via Amazon MTurk, a gig-working website owned by Amazon. Respondents were paid to fill out a 10-minute survey, hosted on the Qualtrics survey platform, on their experiences with gig working. The relatively small sample size, due in part to our targeted effort to sample gig workers, means we do not perform any weighting.

Our overarching research objective for this project was to better understand the types of policies that gig workers in Canada are most likely to support. After collecting standard demographic data and data on the type and frequency of gig work done by the participant, we conducted a conjoint experiment to determine which factors are important for defining who is a gig worker. We then asked respondents why they have chosen to do gig work. We measured perceived social status using an established self-perception tool. Finally, gig workers were asked their preferences for several gig-work-specific policies.

Who is a gig worker?

The gig workers surveyed skewed more male (58 percent), white ethnicity (56 percent), with Canadian citizenship (88 percent). Rather than rely on our small sample to provide descriptive personal characteristics for gig workers, we instead perceptions of who is a gig worker in Canada, according to gig workers themselves.

Firstly, there is no meaningful interaction with gender or perceived ethnic identity; gig workers are not defined by personal-level characteristics. Secondly, ; this may be due to a phenomenon by which gig workers who work more than 20 hours are no longer viewed as performing gig work, but rather a full-time job. Gig workers who rely on gig work for up to 60 percent of their income are increasingly likely to be identified as gig workers, again separating these workers from gig workers who receive all of their income from gig work. . When some, but not all, of their income comes from gig work, they are more likely to be classified as a gig worker. Both of these patterns are consistent with a view of gig work as an addition to other work.

Finally, the strongest predictor of gig work is the task being performed; graphic-design work, even when controlling for other characteristics, is not seen as gig work by other gig workers. The substance of gig work appears to matter as much as the format.

Why gig work?

Gig workers are motivated to pursue gig work by a number of factors. One respondent indicated “gig working is excellent for me in particular though, as I have a disability, and sometimes can work, and sometimes need an extended time off for illness.” We surveyed several common responses for why gig workers have previously indicated preferences for gig work.

- 50 percent indicated it was due to the job’s flexibility;

- 40 percent said the tasks are “easy/straight-forward;”

- 33 percent indicated it was “hard to get other work;”

- 25 percent said the “wages are good;”

- 20 percent indicated it was due to the enjoyability of the work, and;

- 5 percent were motivated by the ease with which you could begin working.

Some respondents indicated they were working because of “boredom due to the pandemic lockdowns,” or they “find it a fun way to earn a few extra bucks.” Others said they were merely gig working as a placeholder until they can find less precarious work:

“As a recent graduate from a master’s program, I have been trying to find a great entry professional job. In the meantime, I am doing gig working. Although I am participating in the gig economy currently, I am completely aware that my employers are using me and paying me unfairly. There is a huge disbalance between my productivity and importance to their tasks, and what I am being paid. I just wanted to note that, although I am participating in it, I strongly believe, in many scenarios, these are not beneficial agreements for the employee.”

While many gig workers are clearly motivated by the flexibility the work provides, it is clear from the written responses that gig work is a backup option, a placeholder until more secure work can be attained.

How do gig workers view their social status?

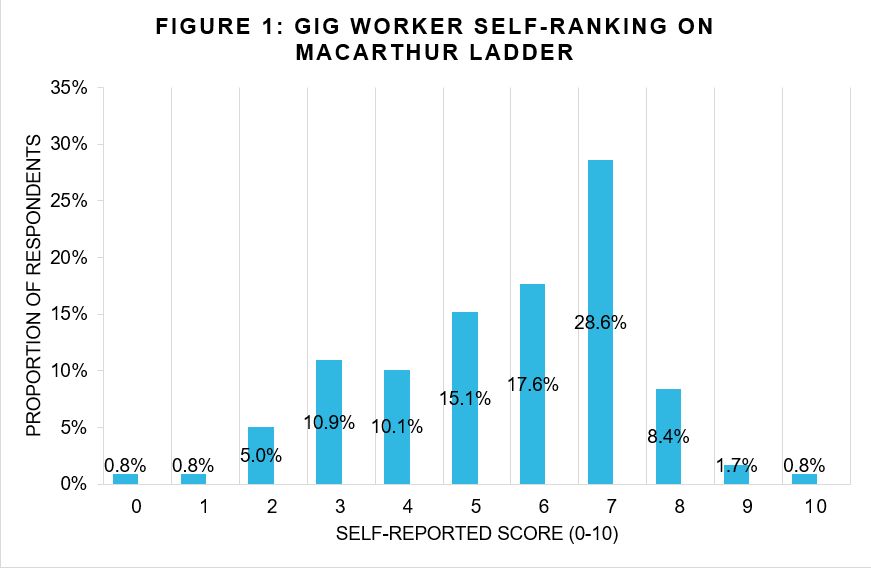

We used the MacArthur ladder approach to determine how gig workers in Canada perceive their own social status. We asked respondents:

Think of the scale below as representing where people stand in Canada. At 10 are the people who are the best off — those who have the most money, most education and most respected jobs. At 0 are the people who are the worst off — who have the least money, least education and the least respected or no jobs.

Where do you think you are on the scale?

Gig workers report relatively high scores, with less than 18 percent of respondents indicating a score of three or lower on the ladder. A large proportion of respondents, almost 40 percent, indicate a score of seven or higher. Just over 40 percent of respondents indicate a score between four and six. This middling effect among gig workers suggests some believe their own position is better than fellow gig workers, but perhaps worse off than those with less precarious employment. This finding is bolstered in some of the open-ended responses:

“I wonder how [many gig workers] are doing this due to an inability to afford shelter/food from their day jobs? My spouse and I earn a high income in our mid 20s but I feel like we have no chance to get ahead due to generational wealth propping up the housing market.”

Which policies do gig workers favour?

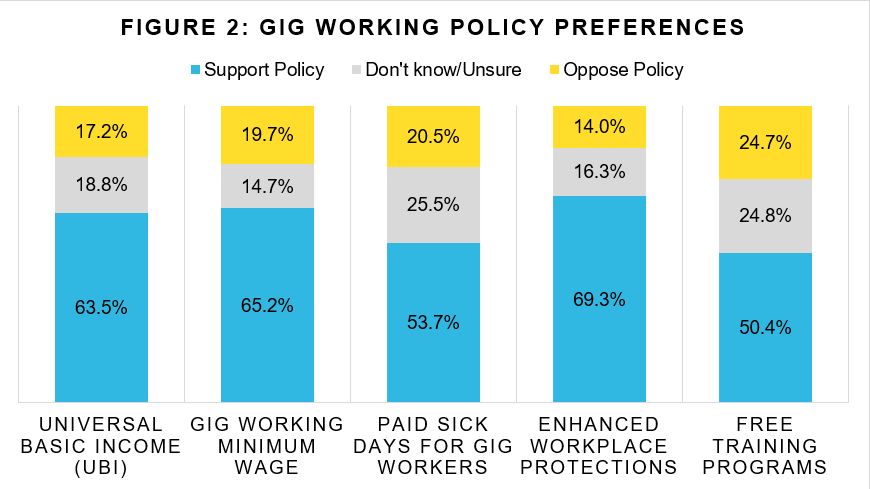

Given the great uncertainty expressed by gig workers, which policies do they favour? We surveyed a number of policies supported by the Foodora ‘Foodsters’ union during its negotiations. The popularity of these policies is displayed below in Figure 2.

Enhanced workplace protections, in which the government increases “the amount of workplace protections for gig workers, including paid breaks, the right to unionize and recourse for wrongful dismissal,” was the most popular proposal, at 69.3 percent overall approval. In comparison, free training programs, which would allow gig workers to gain skills needed to switch careers, and mandated paid sick days for gig workers were slightly less popular. Overall, with all policies above 50 percent popularity, gig workers are eager for policy change.

Although seemingly popular, some gig workers were concerned that instituting these policies could lead to negative repercussions long term for gig workers who do gig work more infrequently:

“I think gig work is what it sounds like. It should not be someone’s only source of income because it is so unpredictable and comes with no benefits. It should be additional income but, because people are desperate for work, they work full-time gig jobs. This isn’t necessarily the intention of the companies offering this work and making them pay breaks/benefits/minimums will ruin it for people doing it on the side of other employment.”

What is role of government?

Government has an opportunity to act meaningfully to address concerns associated with the precarious nature of gig working. As one respondent argues:

“I feel that regulations need to be in place for people who rely on it as a primary source of income. The amount of pay earned is too low in most cases for the time spent on tasks.”

Gig workers are eager for government policy that allows for “stable flexibility,” policies that remove uncertainty while retaining flexibility, including workplace protections, paid breaks, the right to unionize, and recourse of wrongful dismissal.

About the Authors

Peter Loewen is a Professor in the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy and the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto. He also serves as Associate Director for Global Engagement at the Munk School. He is interested in how politicians can make better decisions, in how citizens can make better choices, how governments can address the disruption of technology and harness its opportunities, and the politics of COVID-19.

He has published in leading journals of political science, economics, psychology, biology, and general science, as well as popular press work in the Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, Globe and Mail, National Post, and Ottawa Citizen. His research has been funded by SSHRC, the European Research Council, the Government of Ontario, and other organizations. He regularly engages in public debate and acts as a consultant to several public and private organizations.

Previously, he served as the Director of the School of Public Policy & Governance and the Centre for the Study of the United States at the Munk School of Global Affairs. He is a distinguished visitor at Tel Aviv University, and was previously a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. He has held visiting positions at Princeton University and the University of Melbourne.

Blake Lee-Whiting is a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto, and a Research Fellow in the Policy, Elections, and Representation Lab (PEARL) at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. His research focuses on Canadian politics, political staffers, and the disruptive effects of emerging technologies.