Pandemic Learning: Paid Micro-Training Opportunities for Post-Pandemic Recovery

Brave New Work Blog SeriesBy Peter Loewen and Blake Lee-Whiting

A cornerstone of the federal government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been providing substantial income support to Canadians. This support kept families afloat, bolstered consumer confidence, and enabled many Canadians to stay at home to avoid infection. This approach has been a success. But what if, as part of a recovery package, government expanded this approach to include paid training programs? What if, for example, it had asked them to engage in reskilling or upskilling through short online courses in exchange for additional payments? We argue in this post that there would have been substantial support for this.

As the Canadian government considers post-pandemic recovery benefits, there is an opportunity to upgrade the skills of Canadian residents while providing post-pandemic economic relief. Canadian residents are eager to upgrade their job skills but, especially given the pandemic, those people for whom training would most improve their job aspects are financially hindered from pursuing additional job training. Governments can either ignore the immense talent pool of Canadians most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic or respond by providing innovative new job training policies, reflective of the policymaking lessons learned during the pandemic.

This blog post examines the popularity of a post-pandemic paid micro-training program to help Canadian residents who were most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic improve their skillset while providing financial benefits. To study this approach, we ask if there is demand in Canada for paid micro-training programs among Canadians who have been negatively financially impacted by COVID-19. Our results suggest that:

- Canadians who have been negatively impacted by the pandemic are eager to receive government-assisted skills training;

- The majority of Canadians are eager to take paid life skills courses;

- Course time and remuneration is more important to Canadians than course topic when it comes to micro-training.

Pandemic-Era Policymaking

On March 25, 2020, one day before the Canadian federal government implemented the Quarantine Act in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the COVID-19 Emergency Response Act received royal assent. Among several policies intended to counteract the negative economic impacts of the pandemic was the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), which provided a $2,000 per month taxable benefit to residents of Canada that earned at least $5,000 in the 2019 tax year but had to stop working involuntarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The early days of the pandemic was a unique moment of “cross partisan consensus on important questions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as its seriousness and the necessity of social distancing.” Across the political spectrum, there was a general sense that major measures were needed to reduce the severity of the pandemic. The response by government was a new policymaking approach, wherein broad actions were taken quickly to maximize impact. PPF Fellow Jennifer Robson argues that “relative to pre-COVID-19 income support policy, [there] was a move to pay benefits on the basis of attestations by applicants rather than holding benefits until documentary evidence could be submitted, verified, and approved to support the claim.”

As Canada seeks to emerge from the pandemic, the federal government could consider expanding this “trust-but-verify” approach to policymaking during the recovery phase of the pandemic to maximize support while minimizing barriers to receiving benefits. One such way continue this approach is to implement a unique skills training program in which Canadians are rewarded financially for upgrading their job and life skills. This program could be targeted towards Canadians most affected by the pandemic, or merely to those who are interested in receiving a small benefit for completing an online course offered by the government.

To test the popularity of such a program, our lab (PEARL at the University of Toronto) surveyed 1,291 Canadians, including Canadians in every province, in May and June of 2021 using data provided by Abacus Data via Fulcrum, and hosted on the Qualtrics platform. Survey respondents reflect the age, gender, and regional of Canadians, acting as a mostly representative sample of the population. Further weighting of the data does not substantially change the results.

Our goal was to see what kind of reskilling people would be willing to take on, with a focus on those who received government income support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, after collecting standard demographic data, respondents were asked if they had received federal aid during the pandemic and, if so, what amount of aid and from which programs. We administered the substantive questions described in our results section and administered a conjoint experiment. Finally, respondents were asked if they had lost a job or any income because of the pandemic.

Results

We provided respondents with the following hypothetical scenario:

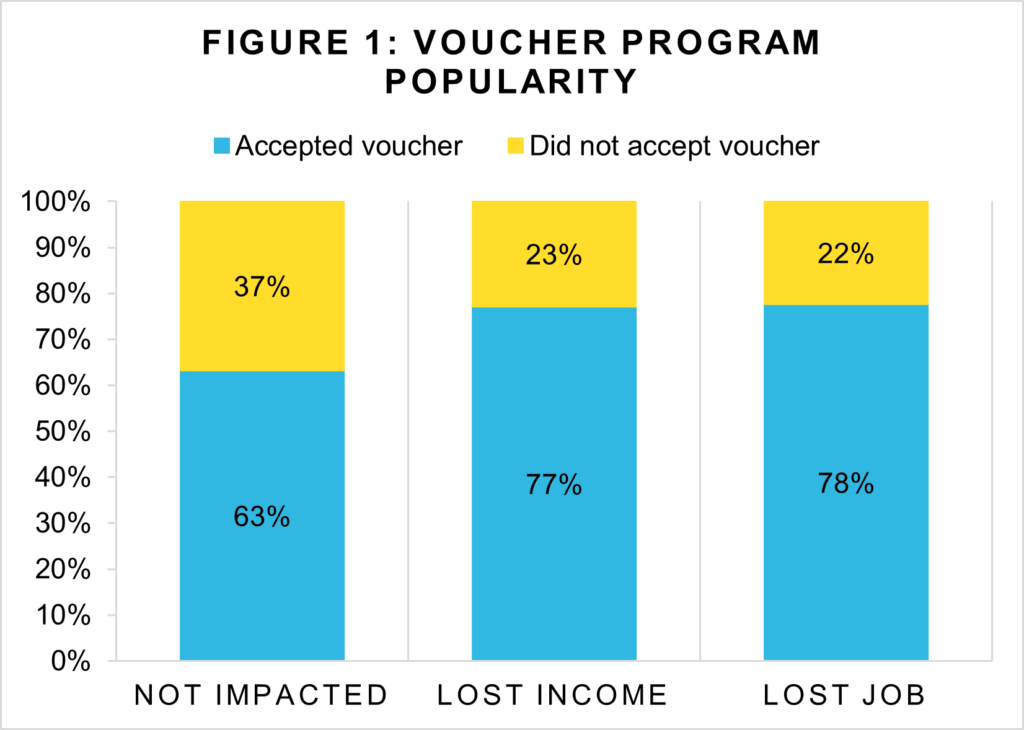

Imagine that the Canadian federal government decides to offer you a voucher for a free course of your choice at any designated educational institution (accredited colleges or universities) so long as the institution accepts your application to take the course. Would you use this voucher program?

Across all groups, the voucher program is relatively popular; 67% of all respondents indicated that they would accept the program. For those who have either lost a job or income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the voucher program is even more popular. As Figure 1 demonstrates, 78% of respondents who lost their job and 77% of respondents who lost income said they would accept the course voucher, compared to 63% of respondents who report not being financially impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadians who have been negatively impacted by the pandemic are eager for skills training.

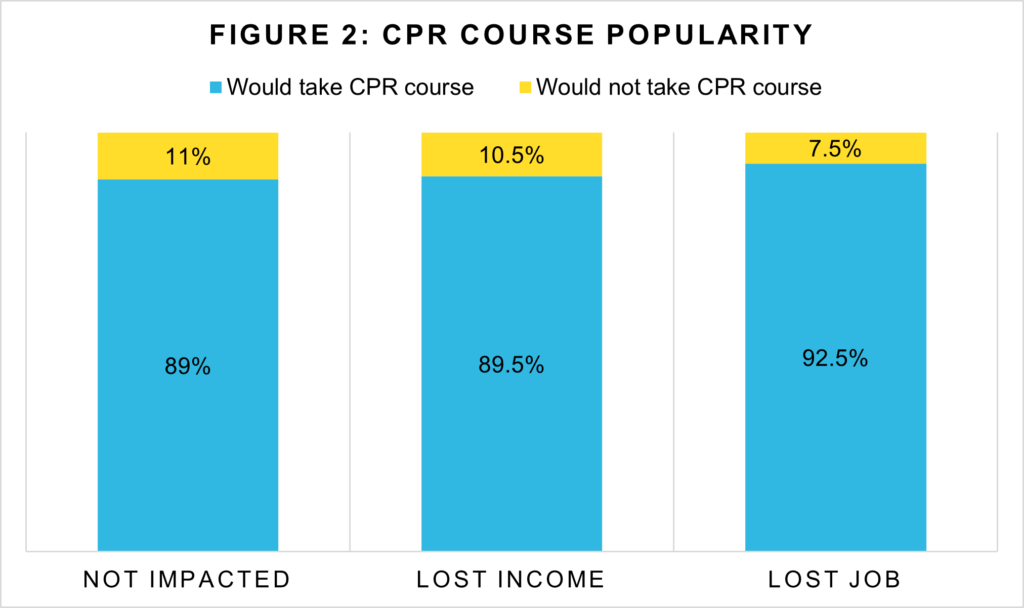

What about more general skills training? To gauge this, we use cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) as a benchmark. Unlike university or college courses which offer more generalized learning opportunities with more diffuse benefits, CPR has targeted health benefits for Canadian society that are immediately apparent; while some professions, particularly those in the health science fields, require CPR training, the premise here is that the Canadian government has an opportunity to provide an important life skill to Canadians as part of a COVID-19 recovery plan.

We gave Canadians the following prompt:

Imagine that the Canadian federal government decides to offer you $100 to take a 2-hour online course on how to properly administer CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation). Would you take this course?

This course offering is immensely popular among Canadians: 89% of respondents who report not being economically impacted by the pandemic indicated that they would take the CPR course. This course offering is more popular still among Canadians who have been negatively impacted by the pandemic; Figure 2 shows that as the impact of COVID-19 increases, the popularity of the program increases slightly.[1]

While we examined two more general program designs, a course voucher for a university or college class and a paid CPR course, we also conducted a conjoint experiment to examine potential program designs. We presented respondents with several different program designs, varying topic, the time commitment of the program and the eventual payout. The conjoint preamble read as follows:

Imagine the following hypothetical scenario: The Canadian federal government has decided to create a program where you are rewarded for taking an online course on (“basic life support skills, such as how to do CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation], taught by a medical health professional”; “nutrition and at-home exercise techniques taught by an expert”; “how to file taxes in Canada as well as some financial literacy information taught by a professional accountant”, “Indigenous history and culture taught by an Indigenous scholar”). Completing the course and passing a short (15-30 mins) test will result in you being paid (“$50”, “$100”, “$200”). The course will take you roughly (“2″,”5″,”10”) hours to complete. The course is taught online using pre-recorded videos and content, so that you can learn and participate at your own speed. Would you sign up to take this course?

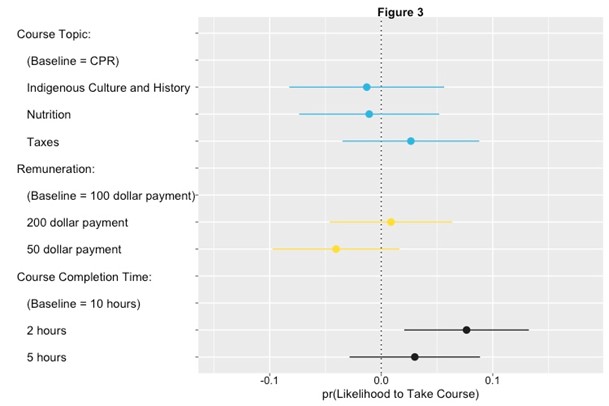

Figure 3 presents our results, estimated across all respondents. Each dot on the figure shows the increase in likelihood of people choosing a program given a characteristic. The horizontal lines are estimated confidence intervals. The dotted line indicates the mean baseline willingness to take the course; a circle to the left of the line indicates that characteristic decreases the likelihood of taking the course, while a circle to the right of the horizontal line suggests the factor increases likelihood above the average.

Our results are important. While respondents are more interested in shorter courses, the amount they are paid for each course does not much matter. Indeed, on the course length variable, respondents are 8 percentage points more likely to take a course that takes two hours to complete than a course that takes 10 hours. We do not find meaningful differences across the four topics, which indicates the government could offer a variety of courses, perhaps targeting them according to known and anticipated labour market needs.

Implications

The Canadian pandemic benefits plan has prioritized providing emergency aid to as many Canadians as possible. As Canada seeks to recover from the pandemic, Canadians who have been negatively impacted by the pandemic are eager to receive government-assisted skills training; many Canadians are likewise eager to receive paid life skills courses. This program design, in which Canadians are paid to upgrade their skills, could help to backstop the economy during the recovery period. Additionally, it could spur universities to create more online micro-content, help more Canadians develop the practice of lifelong learning, and shore up critical knowledge gaps in Canada’s workforce.

[1] Note here though that there are major ceiling effects, so any potential increase will naturally be limited.

Thank you to our partners

Thank you to our lead sponsor

Thank you to our partners

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|