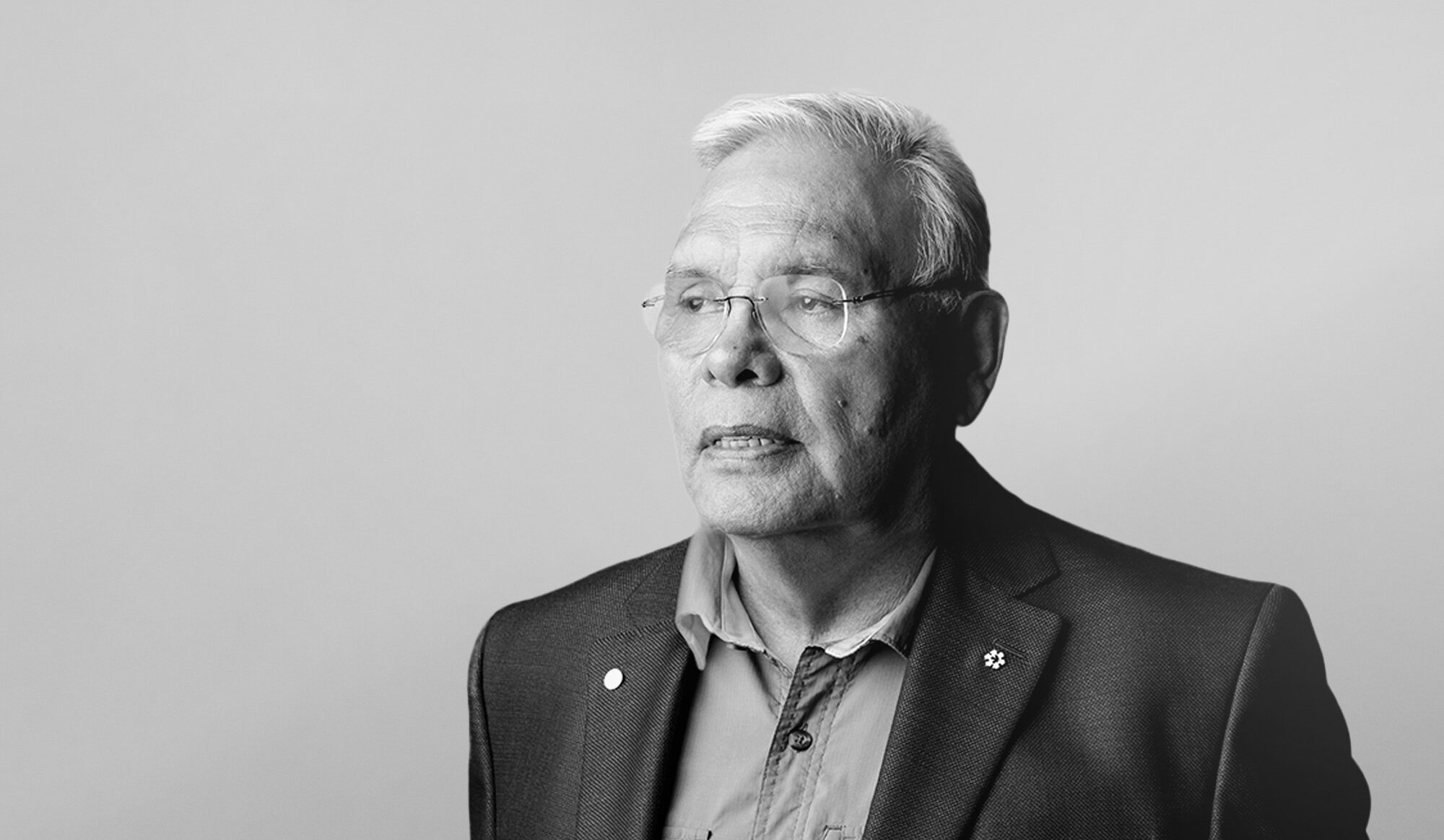

Chief Mi’sel Joe — Frank McKenna Awards 2024 honouree

“As a young man, I traveled across the country, and it was rough at times. But I learned many lessons. You have to earn respect, and you also have to be respectful.”

“What kind of Indian are you?” asked a young man in a rooming house when Chief Mi’sel Joe arrived in Halifax at the age of 16, looking for work and to explore life beyond his community in Conne River, NL.

“I’m a live one,” he replied.

“I thought we killed all of you guys.”

“Well, you didn’t get them all. I’m here.”

That exchange was the beginning of Chief Joe’s informal education in how to assert himself and promote the story and needs of his people, turning him into a beloved leader — the longest serving Mi’kmaw chief in Atlantic Canada — who stood up to government and church officials as he developed his community into a thriving success story.

He had left his home with $10 in his pocket because he felt there was little choice. There was no running water, no sewers, no electricity, no opportunity in Conne River. Across Canada, he worked in many jobs: ranch hand, truck driver, fisherman, underground miner, railway worker.

Ten years later, in 1974, he returned to Miawpukek First Nation, homesick for the sea. His uncle, who was Chief at the time, encouraged his nephew to get involved. He started training heavy equipment operators, pipe layers and pipe fitters, carpenters, plasterers and painters. “We wanted to build a community and have our people do it.”

Tragedy struck in 1982 when his uncle died in a car accident. “Very foolishly, I put up my hand” for nomination as Chief. “I didn’t have a lot of experience in terms of leadership,” he says. But he had determination — and a family legacy to uphold. Both his grandfather and his uncle held office as Saquamaw, or chief. Morris Lewis, the first appointed Chief in Newfoundland by the Grand Chief in Mi’kmaq territory, was his great, great uncle.

Soon after his election as Chief, he was embroiled in a confrontation with the Newfoundland government that would define his leadership. For 13 months, the community had gone without federal funding as his uncle was unwilling to accept the province’s proposal to take $60,000 for an administrative fee and to send in an “Indian agent” to oversee financial matters.

“I said, ‘I’m going to St. John’s and I’m going to try to get our money back.’ It was like poking your hand into a rattle snake’s cage and hoping that you don’t get bitten.” After some false promises, Chief Joe and others staged a protest. “We were told to be a good Indian and go home.” With others from his community, he decided to go on a hunger fast while still in St. John’s. Nine days later, the government capitulated.

Chief Joe, who has been recognized with a Honorary Doctor of Laws from Memorial University as well as an appointment to the Order of Canada, speaks about the injustices that Indigenous people have suffered with calm assertion and no trace of anger or resentment. “Sir John A MacDonald’s whole idea of creating the Indian Act was to destroy Aboriginal people,” he says matter-of-factly. He worked to reform his community’s education system, making sure “that the Church never got their dirty paws on our school,” he is quoted as saying in a previous interview. Now, they have an immersion program in their language and Mi’kmaq studies for high school students.

Through the years, Miawpukek First Nation, which has a population on the reserve of approximately 900, has built housing, a community centre, a clinic, a school and multiple businesses, including a craft store, gar bar, a senior citizen building and partnerships in the fishing industry. There have been mishaps. In the late 1990s, they invested in a fish business that went bankrupt, losing $3 million. Indian Affairs wanted to get involved but Chief Joe refused. “We got in trouble, and we need to know how to fix it ourselves.” Which they did.

Six weeks after retiring as Chief earlier this year – he retains the title “until he goes on his spirit walk” explains his assistant – he was asked to help World Energy GH2 with Project Nujio’qonik, a wind-powered hydrogen plant in Bay St. George. As strategic advisor, he will support Indigenous, government and community relations.

“As a young man, I traveled across the country, and it was rough at times. I had to fight my way in. But I learned many, many lessons from that. You don’t get very far by insulting people, by pounding on a desk. You have to earn respect, and you also have to be respectful.”

Read about the other Frank McKenna Awards 2024 honourees, Dr. Anya Waite and Laura Lee Langley.

PPF’s Frank McKenna Awards 2024 celebrate leaders whose ingenuity and initiative are helping to drive change in Atlantic Canada. This year’s event will take place on Oct. 10 at Pier 21 in Halifax. Register now.