Immigrant entrepreneurs: Highly desired, hard to attract

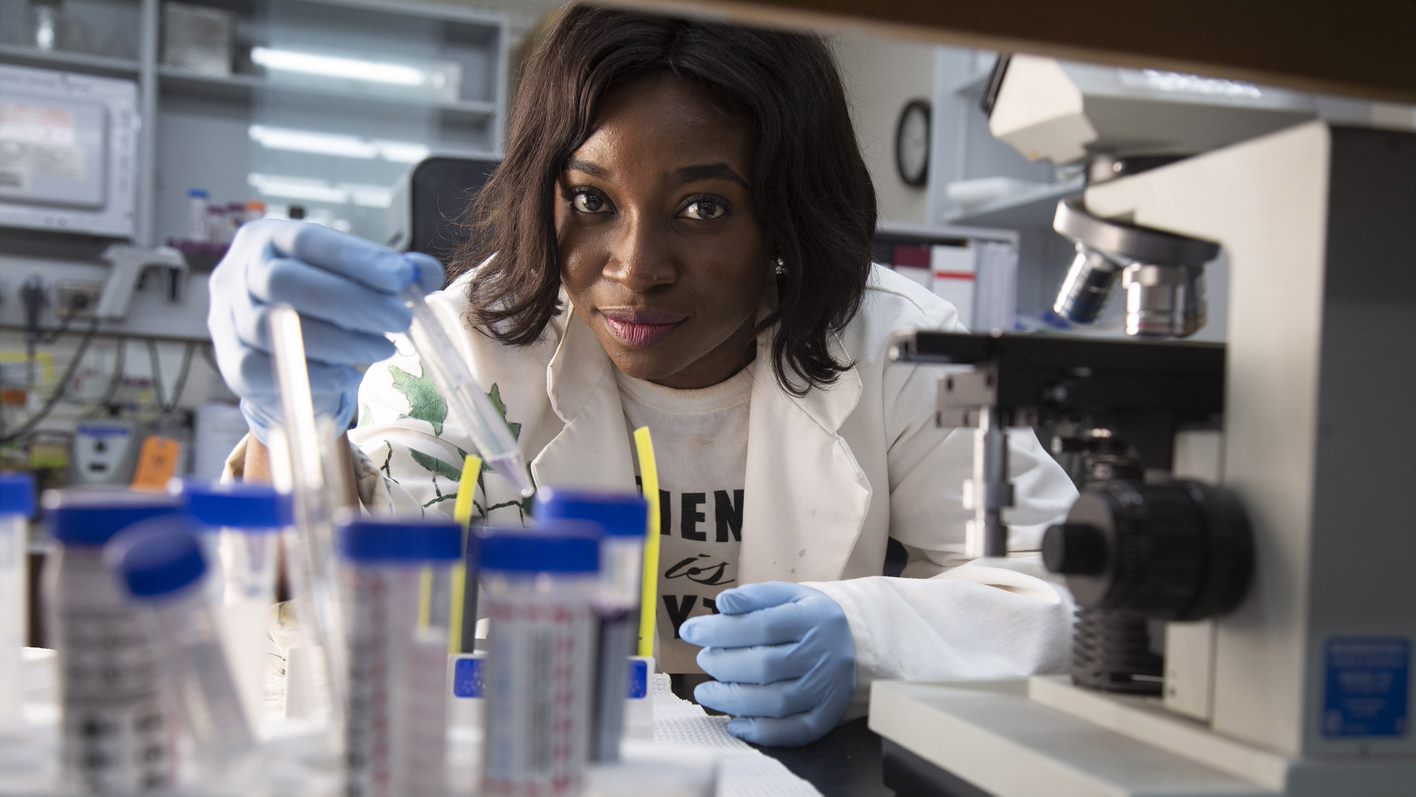

Cover Photo: Modeline Longjohn: A student at MUN

It is the gold standard for immigration—attracting newcomers who arrive with the money, desire, skills and temperament to start a new business that will employ local residents, generate tax revenue, increase economic activity and boost community well being.

But figuring out which newcomers will be successful entrepreneurs is not easy. The policy field of immigrant entrepreneur programs is littered with well-meaning failures: programs that sparked a raft of bogus businesses; programs that attracted immigrants who had money but few other qualifications; programs where the benefits flowed to well-connected local businesses or government agencies; programs that were so strict that they turned away legitimate entrepreneurs; programs that discouraged innovation.

It is a worldwide quest. Policymakers from France to Australia and more than a dozen other countries have struggled with how to create the right mix of incentives and requirements to find those winning newcomers. Atlantic Canadian provinces were some of the very first in the game.

“The places that do best already have strong pro factors,” says Stephane Tajick, a Montreal consultant who monitors business immigration programs around the world. “They are places where people actually want to start a business: Hong Kong, Singapore, Dubai, Switzerland.”

Advice from Atlantic Canada’s immigrant entrepreneurs: Click the photos to read their stories

Why the quest for entrepreneurs?

A suite of new research, using several measures, shows that businesses started by immigrants outperform businesses started by Canadians.

Immigrants have a higher rate of business creation than Canadian-born citizens. And the longer they stay in Canada, the higher their likelihood of starting a business. One 2016 Statistics Canada study found that 11% of immigrants who arrived in Canada in 2004 generated the majority of their income from self employment six years later. The self-employment rate of the comparison group was 7.5%. That study found that over the long term, immigrants were more likely to start private corporations and small businesses than Canadian-born entrepreneurs.

Another recent study by Statistics Canada found that immigrant-owned businesses create more jobs than Canadian-owned businesses. That study also found that immigrant businesses were more likely to grow quickly. Another Statistics Canada study released in May shows that immigrant businesses are much more likely to engage in international trade with their home region than their Canadian counterparts.

New businesses are not the only economic benefit of entrepreneurial immigrants. Newcomers, it is hoped, will take over from the thousands of baby boomer business owners who want to sell their stores, factories and service outlets so they can retire.

The problem is particularly acute in Atlantic Canada. A 2017 study by Industry Canada found that Atlantic Canada’s business leaders are the oldest in the country, with 69% of all the primary decision makers over the age of 50. The same study found that 27% of all businesses in Atlantic Canada expect to close or be sold within five years—the highest rate in Canada.

Francis McGuire, president of the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, is one of many regional leaders pushing immigration as an economic necessity. He has been traveling the region, warning business leaders, community groups and politicians that the crisis of business succession may only be solved by bringing newcomers to keep the lights on as Canadians retire.

Beyond the solid economic reasons to attract immigrants who start or buy businesses, there are also social and political reasons.

Some research shows that anti-immigrant sentiment in Canada is directly tied to fear that immigrants will compete for jobs. Research presented by Saint Mary’s University professor Ather Akbari at the National Metropolis Conference this spring shows that the more people feel financially insecure, the more they resist increased immigration to Canada.

A poll conducted by Leger Marketing found that 45% of Atlantic Canadians who are “very worried” about their personal finances think there are too many immigrants in Canada. Only 24% of Atlantic Canadians who are “not worried at all” about their finances think there are too many immigrants in Canada.

What’s been tried?

It’s obvious why governments want to recruit immigrant entrepreneurs, but it turns out that attracting and keeping them is surprisingly hard to do.

The Maritime provinces were among the first in Canada to try recruiting entrepreneurs with a specific immigration program designed just for them. It is rare that a complex policy works well from the beginning. These didn’t. Some believe that those early failures made policymakers overly cautious and led to programs that are too restrictive to be useful.

The first entrepreneurship programs in Atlantic Canada required that immigrants invest in local businesses, in the theory that they would benefit from the mentorship of local business leaders. In practice, some immigrants saw the investment as simply the price to get in the country, and some businesses saw it as a way to augment their income.

In 2008, the Nova Scotia auditor general issued a scathing report on the system that prompted the provincial government to refund fees and shut it down. The federal government shut down a similar program in PEI in 2008 and provincial whistleblowers later alleged widespread corruption in that program.

Atlantic provinces weren’t the only ones that struggled to get it right. The federal government shut down its own immigrant investor program in 2012 amid allegations of fraud.

The second wave of immigrant entrepreneur programs required immigrants to put money in escrow that they would only get back after running a business for a year. Most provinces abandoned that system after discovering that wealthy immigrants were willing to give up the escrow as the price of doing business, or that they created sham businesses that did not really boost the economy or local jobs. PEI closed its program in September following new allegations of fraud.

Research confirms that the attempt to create new businesses through specialized immigration streams hasn’t really worked. A Statistics Canada study found that immigrant entrepreneurs and Canadian entrepreneurs closed their businesses at about the same rate, but that newcomers who came to Canada through a specific business immigration program exited their businesses at a much higher rate than immigrants who came to Canada through family sponsorship or as skilled workers. Many blame PEI’s failed entrepreneurship program for the fact it has the lowest retention rate of any province in the country.

Canada isn’t the only jurisdiction that has struggled with how to attract and retain entrepreneurs.

Tajick says Australia had a program that was supposed to foster innovation through immigrant entrepreneurs but the country ended up with a bunch of souvenir shops, restaurants and fashion boutiques instead.

“Entrepreneurs will go where they can take the least amount of risk they can,” he says.

Where are we now?

Most Canadian provinces have moved to a two-step process for immigrant entrepreneurs. First the applicant presents a business plan to the province. If the plan is approved, they must launch the business and run it for a year before they receive a provincial nomination for immigration. It takes almost two years after getting the nomination to receive permanent resident status, so at least three years from the time they first apply.

In March 2019, the Conference Board of Canada published a report around improving Canadian business immigration. Their research points out that across the seven running immigrant entrepreneur programs in Atlantic Canada, the majority require that applicants have a minimum net worth of $600,000 and have the intention of owning at least 33.3% of their business.

The new system prevents immigrants from buying their way into Canada by simply depositing money in a government escrow account, but both Tajick and Nova Scotia immigration lawyer Liz Wozniak say the new programs aren’t suited for true entrepreneurs.

Tajick says the business plans are created by consultants and are designed to meet the requirements of the immigration system, not the real needs of the Canadian marketplace.

“Business plans are manufactured for (applicants),” says Tajik. “Someone in Canada creates it. It’s only for the purpose of getting approved for immigration and the applicant may not even really understand what is in it.”

Wozniak says most clients have better, faster ways to become permanent residents. She only uses the Nova Scotia entrepreneur stream for clients who are either too old to garner enough points under other systems, or whose language skills are too low to otherwise qualify.

Wozniak sometimes refers to the custom-built programs designed to lure ambitious business immigrants to Nova Scotia as “anti-entrepreneur” programs because they are so cumbersome and slow.

Not a single entrepreneur has been nominated by Nova Scotia for immigration since its new entrepreneurship program was launched in 2016, although 15 applicants have been approved to start the process and will be eligible for nomination if they operate their business for at least one year. A parallel program for recently graduated international students has generated five nominations, but the first student nominated is still waiting for the federal government to process the application she submitted in 2017. It appears that no one has actually achieved permanent resident status through the current programs in Nova Scotia.

One of the biggest problems with the two-step process is that there is no guarantee the immigrant will succeed. Depending on the program, they must invest at least $100,000 and move to Canada for a year, but they will be turned away if their business doesn’t succeed. With most of the two-step programs, candidates can’t change the business to meet changing market needs. In one case, an applicant was turned down by the federal government even though he had a nomination from PEI and met all medical and security requirements. In that case, a visa officer decided the applicant’s language skills weren’t high enough—even though his tests met the standard required by law. The case is being challenged in federal court.

The Atlantic provinces are still tinkering, trying to get it right.

Nova Scotia recently changed the rules for its entrepreneurship programs. Now immigrants will be able to apply for permanent residency using a business they have already started. Until this spring, they had to have their business plan approved by provincial officials before the company was even registered.

Nova Scotia also changed the path that allows entrepreneurial students to become permanent residents after graduation. The original program required that international graduates own 100% of their qualifying business, cutting them off from the financing and mentorship of experienced Canadian business people. The new rule only requires that the recent graduate own 30% of the business.

After shutting down its main immigrant entrepreneurship program last year, PEI moved to a two-step system and required that applicants be sponsored by a community agency. It is too early to determine how well that program is working.

Newfoundland and Labrador launched its entrepreneur programs—one for regular immigrants and one for recent graduates of Memorial University or College of the North Atlantic—late last year. Those are two-step programs similar to Nova Scotia’s system. They are too new to have generated any applicants.

New Brunswick is the only province left in Canada that still allows immigrant entrepreneurs to deposit money in escrow as a condition of getting a nomination for permanent residency, and then to earn the money back after they start a business in the province.

The future

Just because entrepreneurship immigration programs haven’t lived up to their promise doesn’t mean that immigrant entrepreneurship has stalled—far from it. The wealth of data on immigrant business success shows that. But most of that entrepreneurial activity is coming from immigrants who arrived in the region as refugees, students, skilled workers or family.

Wadih Fares and Tareq Hadhad are two of the best known and most successful immigrants in the region. Fares came to Nova Scotia from Lebanon a generation ago and is now one of Nova Scotia’s biggest developers. Hadhad came to Nova Scotia in 2015 as a Syrian refugee and founded, with his family, the now-famous Peace by Chocolate factory in Antigonish. Joe Teo came to Canada from Malaysia to study business at Memorial University. Carina Lin gave up a lucrative career in China to make candy in New Brunswick.

PPF consulting researcher Kelly Toughill’s latest analysis piece discuses three sets of research that back the claim that support across Atlantic Canada is strong and growing. The desire for more immigrants is there and provinces are starting to recognize that formal immigration streams aren’t the only way to support immigrant entrepreneurs. The Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia has staff dedicated to helping newcomers launch or buy businesses. Memorial University has launched an intense training program for students who want to become entrepreneurs. The program is open to all graduate students, but most of the seats are taken up by students from around the world.

Modeline Longjohn is one of them.

Longjohn is completing a PhD in immunology at Memorial University but has a background in community health in her home country of Nigeria, where she wrote radio dramas about women and cancer. She is thinking about medical school but is dedicated to cancer research. She is also dedicated to helping people get quality healthy information through a specialized phone app she wants to develop.

“I am someone who has a lot of ideas,” says Longjohn. “I want to use my app to integrate different kinds of information, and I want to have enough skills to commercialize it. I have learned so much in this program, how to grow your business, protect intellectual property, budget, do finance, get funding, structure partnerships.”

She is clear that starting a business in Canada is part of her future.

“I wish more women would do the crazy ambitious things that will change the world and change our lives. That’s what I want.”

Many are working on some of the practical problems of encouraging immigrant entrepreneurship. Newcomers may not have access to financing because they don’t have a credit history in Canada. Others may not be able to use traditional loans because religious restrictions prevent them from paying interest. Incubators and start-up labs like Volta in Halifax and NouLab in New Brunswick have welcomed newcomers or set up programs specific to their needs.

Tajik urges Canada and the provinces to focus on why they want immigrant entrepreneurs, and then tailor on-the-ground services to match that goal.

“An entrepreneurship program should have a specific goal,” he says. “Solving the succession problem could be one. There is trillions of dollars in succession coming up. We have an aging population with trouble finding buyers. Suddenly what was worth half a million or a million dollars just vanishes.

“If that’s your goal, then look at problems that emerge: how do you do the link between buyers and sellers? How do we arrange financing for foreign buyers or new immigrants? A lot of challenges need to be answered.”

Tajik also urges policy makers not to forget that luring immigrant entrepreneurs is a competitive market. Canada is vying with scores of other countries for the same people. In many cases, it is agents that guide where those immigrants decide where to go. Other countries are offering a bounty to agents that steer immigrants their way. Canada offers quality of life but a complicated, uncertain and lengthy process. And unlike some jurisdictions, there is no guarantee that even if you follow all the rules, you will get to stay in the end.