More than Just a Rebuild: Creating a better future for Canada

How COVID-19 has shifted businesses’ priorities as they focus on recovery by Georgina Black and Anthony VielIntroduction

COVID-19 is first and foremost a human tragedy, causing widespread suffering and highlighting the deep inequalities in Canada and around the world. The scale of the resulting economic collapse is unprecedented: for the first time since the end of the Second World War, advanced, developing, and emerging economies around the world are all simultaneously experiencing dramatic recessions. In Canada, it has bludgeoned the private economy, forcing governments to take previously unheard-of measures. As Canada takes steps toward restarting the economy, the battle to simultaneously relax restrictions and contain the virus will be waged by governments saddled with high debt levels and constrained revenue.

With such uncertainty comes a desire to see the economy return to normal. But this cannot be our objective. The hard truth is that, before the crisis, the Canadian economy was already stuck in neutral, with stagnant growth, lagging productivity, and declining competitiveness. The crisis has also made it clear that strong economic growth alone is not the answer; the economic gains must also be distributed fairly across society to create opportunities for all Canadians to thrive. Society is not only demanding change to address the inequalities exacerbated by the pandemic, but also the longstanding systemic injustices against many groups in our country, including racialized populations, Indigenous people, and LGBTQ+ communities.

This change needs to be bold—not incremental. For too long Canada has espoused inclusive growth, but failed to make it materialize. We must act immediately and deliberately to avoid a return to normal. The moment demands higher ambition—recovery programs from economic shocks in the past, such as the Tommy Douglas-led development of Social Welfare in Canada, and the Marshall Plan worldwide, reshaped economies and societies, recognizing the need to drive more inclusive growth. Today, government and business must come together to create a better future characterized not only by a strong economy, but also a more resilient and equitable society.

This paper revisits Canada’s most pressing competitiveness challenges, examines how the COVID-19 crisis has changed the nature of the challenges before us, and presents five areas where business, government, and communities must take bold action to achieve a better future for Canada.

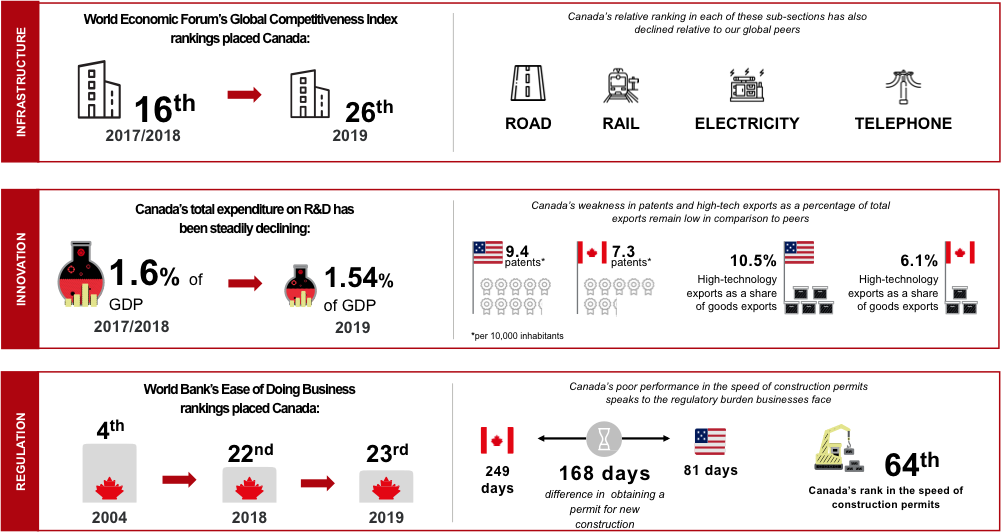

Canada’s sluggish economic growth and competitiveness challenges have been well studied over the years, including by Deloitte. In 2018, we developed our Competitiveness Scorecard to benchmark Canada’s global standing, which revealed that our nation’s decades-long trend of lagging productivity and declining competitiveness was dragging down our prosperity and living standards relative to our peers. Three of the biggest challenges we highlighted in the Scorecard (Figure 1) were:

Infrastructure: The 2017/18 edition of the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Competitiveness Index ranked our infrastructure 16th in the world with weaknesses in road, rail, and electricity/telephony infrastructure. Since then, our ranking has declined to 26th, with associated declines in each sub-ranking. Also, while digital infrastructure was not explicitly highlighted in the original competitiveness scorecard, the WEF ranked Canada 35th in the world in 2019.

Innovation: Canada’s total expenditure on research and development as a percentage of GDP has only continued to decline since the scorecard’s release, with our 2019 spend down to 1.54 percent, well below our peers in other developed countries. Canada’s weakness in patents and high-tech exports as a percentage of total exports also failed to materially improve.

Regulation: In 2019, Canada ranked 23rd (down from a high of fourth in 2004) in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Ranking. Our poor performance in the speed of construction permits (64th) and obtaining a permanent electricity connection (124th) highlights the regulatory burden businesses face.

Our weak competitive position going into the pandemic makes our recovery from it more difficult. Canada’s weakness in infrastructure holds back both trade and investment. Our lack of innovation means that our businesses don’t have the cutting-edge technology or skills needed to compete with their global peers. Our regulations mean that businesses will find it that much harder to grow. These challenges were slowing our economic growth prior to the crisis and will continue to do so post-crisis. For example, pre-pandemic, we estimated that the Canadian economy would grow at 1.6 percent annually over the next decade[1]—already significantly lower than annual average growth of 2.2 percent in the preceding decade.[2]

Not only has our economy has been stuck in the slow lane, we’ve also been failing to grow in a more sustainable and inclusive way. For example, as of 2017, Canadians produced the tenth highest CO2 emissions in the world, and the third highest per capita. Deloitte’s 2017 report on diversity and inclusion also highlighted how women, recent immigrants, and people with disabilities are still underrepresented in the workplace. And there are many other issues our nation has failed to address regarding environmental sustainability, equity in our societies, and our global standing.

COVID-19 has led to a deep and significant shock to Canada’s economy, which will have profound effects. Some of these include:

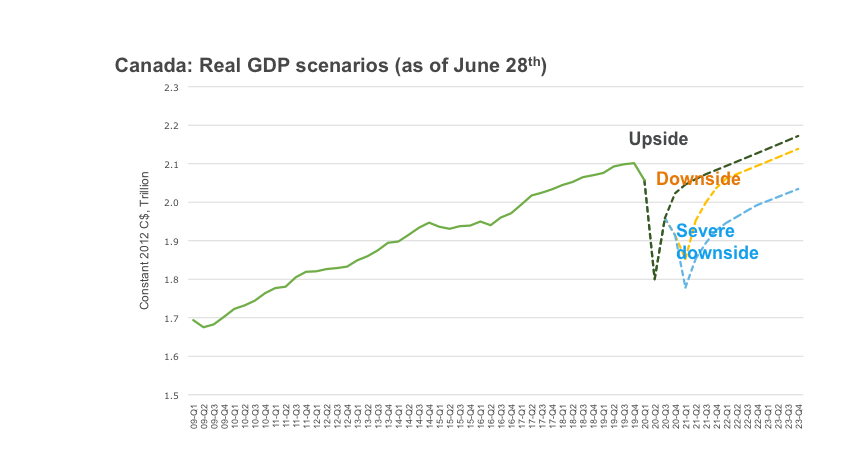

- Economic growth: Canadian real GDP will shrink for the first time on a yearly basis since 2009, and will likely represent the sharpest single-year GDP decline since the end of the Second World War.

- Unemployment: We will face elevated unemployment for a considerable time—with the unemployment rate not expected to return to pre-pandemic level until after 2022.

- Small business: Many smaller businesses will not survive. According to a survey by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, 32 percent of small business owners are unsure if they will ever be able to reopen.

Canada’s path to recovery is uncertain, shaped by the continued health impacts of the virus and its effect on the resumption of full economic activity. Based on how the Canadian economy is currently tracking, Deloitte’s forecast suggests the economy will not recover to pre‑pandemic levels until Q1 2022 in real terms (Figure 2), and our unemployment rate will take even longer to bounce back. There is also downside risk to these projections, based on health-driven factors such as subsequent waves of virus outbreaks, which we account for with our alternative downside economic scenarios.

Figure 2: Canadian real GDP and projected GDP

The effects of the crisis have been felt unevenly across Canadian society. From a health perspective, the elderly and racialized communities have faced the brunt of the most serious consequences of the pandemic, and public health systems are struggling to collect and analyze data to protect populations that are more vulnerable. From an economic perspective, the collapse of the service sector in particular has disproportionately affected certain segments of workers, including:

- Women: Employment for women declined 16.9 percent between February and April, compared to 14.6 percent for men.

- Youth: In June, Statistics Canada reported that youth unemployment[3] had reached 28.9 percent, the highest rate among any age group.

- Part-time workers: Compared with February, part-time work was down 27.6 percent in May, while full-time employment was down 11.1 percent.

The recession has also not affected the entire country in the same way—certain industries, sectors, and regions have been hit much harder than others. As our economy begins to recover, certain industries and sectors have much higher potential to grow quickly, whereas others risk being left behind. This means that without significant shifts to our economic activity, Canada’s path to economic recovery will not be able to rely on the past engines of our economy—such as the extractive, manufacturing, and retail and recreation industries—to drive our future growth. Absent concerted effort and support to reinvent these industries, we will need to chart a new path to prosperity driven by potential high-growth industries, such as health, life sciences, telecoms and data, and areas related to e-commerce such as transportation and warehousing.

Some regions of the country also face a much tougher road to recovery, as pre-existing factors (in particular, the decline of oil prices) have amplified the economic shock of the pandemic. In April this year, oil traded at negative prices for the first time in history. While the price of oil has recovered from its lows, it remains below pre-pandemic levels and oil-producing provinces—particularly Alberta and Newfoundland and Labrador—have suffered from both the fallout of the pandemic and the global oil shock.

The COVID-19 crisis has amplified Canada’s long-standing growth and competitiveness challenges. It also adds significant complexity to how we balance policies to support our economic recovery and growth, while addressing the social inequalities magnified by the crisis. As we emerge from the crisis, can we transform our economy and society? And if so, how and where do we begin?

To help answer these questions, we reached out to Canadian business leaders from across the country through surveys, interviews, and roundtables for their views. The pandemic has magnified the structural weaknesses in Canada’s economy, and it will also leave some lasting legacies. Some of these, such as the accelerated adoption of digital technologies, will serve to improve Canadian productivity and competitiveness. Other legacies, such as our increased debt load, may compound our competitiveness challenges by limiting the tools available to government to stimulate the economy. The insights from the business community help decipher the trends and legacies that matter to future growth and prioritize the areas to focus on during the rebuilding process. Five areas stand out as requiring bold action to secure a successful future:

Betting on tomorrow’s industries

Canada is an economy in transition, and we need a plan. We are a resource-rich economy which must use the resources available to us to create a smart transition to new industries and a 21st century economy. There are many industries with the potential to drive future growth for Canada. Now is the time to place bold bets, targeting those industries that can create jobs, stimulate trade, spark innovation and entrepreneurship, and position Canada competitively in the world. Governments, business, and communities should come together to focus investments on industries that have the potential to drive the economy forward. This requires trade-offs, calculated bets, and alignment of infrastructure investments to harness the promise of certain industries to drive growth.

The debate over resource extraction is particularly significant as it concerns an industry that has for many years been at the very heart of wealth and prosperity generation for Canada. We must confront two truths: first, that we are a resource-rich economy and must continue to capitalize on this in order to build prosperity; and second, that our future must be sustainable, and we must find a way to reduce reliance on carbon-intensive energy sources. It is a false dichotomy to pit these two truths against one another. Canada can continue to capitalize on existing resources, while also making strategic bets on the technologies that will underpin our sustainable future. We have an opportunity to be a global leader in cutting-edge technologies like hydrogen fuel, carbon capture, and carbon fibre—technologies which build on existing industries and expertise, while also contributing to emissions reduction at home and abroad. But our old sustainability playbook will not work if we truly want to lead on these technologies—that will require business and government to collaborate on initiatives that create a competitive advantage for Canadian firms.

Infrastructure to be future ready

Investment in infrastructure must be a priority for governments and business if we are to lay the foundation for Canada to thrive long term. Our transit, ports, electricity, and telephony infrastructure all continue to hold back our country’s competitiveness. Taking inspiration from our history, governments should look to infrastructure as a way to stimulate the economy, build resilience to environmental and economic shocks, and enable a new period of growth. The creation of a national Infrastructure Bank was a good first step. Governments at all levels must now refocus on treating infrastructure as a national priority and one of the key enablers of growth, with particular focus on new funding models and partnerships that account for fiscal constraints while ensuring equitable access. Infrastructure must not become a casualty of governments seeking fiscal rebalancing in our post-COVID environment.

It is also time for a national strategy for digital infrastructure, both hard infrastructure and enablers, to lay the foundation for Canada to thrive. Digital infrastructure is akin to the railroad and electricity networks that enabled previous industrial revolutions. A national ambition to be a digital country requires investment in digital infrastructure (broadband, 5G), getting on with digital identity, regulatory and privacy reforms, and digital literacy training, all with a commitment to ensure equitable access for businesses and people. There are important questions to be addressed related to the role of business, governments, and citizens and how to pay for all of this to ensure commitments to equitable access are met.

Preparing a future-ready workforce

As Canada rebuilds after the pandemic, and as industries undergo significant transformation, we will need to adopt a modern workforce strategy that enables Canadians to thrive in transition. A modern workforce strategy includes a dynamic employment insurance and skills training system that helps employers and people adjust and prepare for a rapidly changing labour market—and includes gig, foreign, and temporary workers. We must break down traditional conceptions of the education lifecycle that end at post-secondary and instead do more to encourage lifelong learning and on-the-job training, including through new business and government collaborations. A reimagined employment and skills system will prepare Canada to be more competitive as business and government work together to improve productivity.

Ensuring everyone can participate

The challenges of COVID-19 have been particularly acute for certain groups in society. There remains a risk that children and youth will be permanently set back if childcare, schools, colleges, and universities remain closed, and job prospects for graduates remain bleak. Evidence from other crises points to academic and employment setbacks experienced in youth having lasting effects that follow individuals throughout their working lives. There are also increasing concerns that working parents will struggle if childcare and schools remain closed or access unpredictable, impacting their ability to work and their income stability. Data shows this is likely to affect women the most, as they remain the primary caregiver in many households. Data emerging during COVID-19 also indicates that racialized and Indigenous populations are being disproportionately impacted, from both health and employment perspectives. As governments focus on reshaping the economy, targeted and integrated policies to ensure more youth, women, Indigenous and racialized populations are supported to participate in the economy will not only serve to do the right thing, but will also be crucial to improving Canada’s productivity.

A revitalized approach to healthcare

Underpinning a prosperous country and society is a robust health and social care system. COVID-19 has exposed the frailties of Canada’s fractured health systems, which were designed for a different century. It challenged the country’s resilience and demonstrated that testing, personal protective equipment, and vaccines are essential ingredients of a strong public health system. Perhaps most challenging, COVID-19 shone a light on the uncomfortable realities of health and social care for seniors, racialized, and Indigenous populations, and vulnerable members of society.

The pandemic taught us that countries perform significantly better in a crisis if they invest in advance in the science, data, and technology that enables smarter policy and decision-making, and accountability. Canada has an opportunity to implement these lessons learned in our health and social care systems to improve outcomes for all. Government should commit to a strong pan-Canadian public health system by making investments to better predict, prepare, and respond to future crises, protecting the public. A modernized and coordinated public health system will provide governments with real-time access to information, enabling precise policy interventions that safeguard health and minimize impacts to the economy. A well-orchestrated strategy that emphasizes the health and social care outcomes of seniors, racialized, and Indigenous populations would have the added benefits of accelerating adoption of virtual care, bending the health cost curve and creating the conditions for more people to fully participate in the economy and society.

The scale of the economic and social disruption that the pandemic has brought has highlighted the essential role of businesses—and communities—in crisis response. From individuals to non-profits, to Canada’s largest businesses have worked hand-in-hand with governments to deliver aid and meet urgent pandemic-related needs. In some areas, such as connecting bank accounts to the Canada Revenue Agency to enable quick delivery of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, that collaboration has worked extremely well. In others, the pandemic has exposed weaknesses in governments’ ability to quickly communicate and adapt to user needs. But what has been consistent is a willingness from government to listen to outside voices in developing and changing their response to the pandemic.

Our country has also witnessed an unprecedented degree of coordination, cooperation, and collaboration across our different levels of government. This trend should continue, with each level of government working on their part of a shared single strategy for our country—so that we all rally around the areas and industries where all Canadians can win. When coupled with the increased speed to impact for government—i.e. what once took years now takes months or weeks to solve—government could not just evolve, but undergo a complete revolution, in terms of its effectiveness in dealing with our most challenging issues.

That dialogue and willingness to work towards a common goal must continue. The complexity caused by the pandemic makes setting clear priorities and a path forward for each of the five areas of challenge we have identified difficult. That task cannot fall upon the shoulders of government alone. It will require a national conversation that grapples with the trade-offs inherent to making choices about which actions to prioritize over others. Canadian business and community groups must play a key role in that conversation, in order to create buy in and also because they will need to collaborate far more closely than was the norm pre-crisis if we are to overcome these challenges. This becomes even more pressing when governments across the country shift their priorities from crisis response to recovery: many of the biggest-ticket items that are necessary for future growth will simply be unaffordable and ineffective should individual governments attempt to tackle them alone.

The priority areas highlighted are drawn from preliminary conversations we have had with the Canadian business community. More work is required to unpack the issues and develop recommendations on what business, government, and communities can do to address them. The aim of this paper is to spark debate and support dialogue. For our part, we will continue to gather insights from business leaders and future leaders on how we can transform Canada’s economy and society to enable a prosperous society for all, the results of which will be shared in a subsequent paper.

COVID-19 has shone a light on our need and ability to act decisively as a nation. Some organizations have quickly changed their operations to meet the emerging needs of our society, and some have gone even further to make permanent changes to how they operate. The need to respond rapidly to the pandemic has accelerated the process of making decisions that normally would take much longer. Governments across the country—which have long struggled to match the rhetoric of agility with action—have also shown the courage to take swift, decisive, and bold action.

If we are to set Canada on a better path to prosperity, we need to capture this momentum and infuse this decisiveness and agility into Canadian businesses, governments, and society at large. In the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first 100 days—during which he passed a record number of bills and created most of the New Deal institutions that would eventually rejuvenate the US economy—offers a historical example that both government and business should seek to emulate, especially when faced with unemployment and economic decline that approaches the depths of the Great Depression.

As governments and businesses across Canada shift to rebuilding our economy and society, we have an unprecedented opportunity to redefine the type of country that we want to live in and prepare for a prosperous future. We have long known that we must reshape the Canadian economy and society to be more innovative and resilient—that we should aim higher than the growth rate our country is currently on, and hold ourselves up to our global allies in striving for higher growth and increased productivity. But today, perhaps more than at any other moment in our history as a country, society demands this growth be equitable, contribute to rising standards of living for all, and foster a healthier relationship with our planet.

- Deloitte analysis, 2020-2029, pre-pandemic. ↑

- 2010-2019. ↑

- Defined by Statistics Canada as ages 15 to 24, inclusive. ↑

Partners

Private Sector Partners: Manulife & Shopify

Consulting Partner: Deloitte

Federal Government Partner: Government of Canada

Provincial Government Partners:

British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario & Quebec

Research Partners: National Research Council Canada & Future Skills Centre

Foundation Partners: Metcalf Foundation

PPF would like to acknowledge that the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the project’s partners.