Revitalizing Canada’s Manufacturing Economy for a Post-COVID World

by Meg Gingrich and Mark RowlinsonThe COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the fragility of the international economic arrangements we rely on in times of crisis. In its most acute sense, this took the form of lack of access to essential medical and personal protective equipment in many countries, including Canada. Years of offshoring, outsourcing and just-in-time production left us, and others, ill-equipped to deal with the pandemic.

As a result, many of the world’s countries have turned inward, enacting policies mandating personal protective equipment meant for export must now be used for domestic purposes, cutting off Canada’s supplies of these essential goods. In Canada, the federal and provincial governments reacted swiftly, going as far as bringing supply chains under provincial control,[1] though the lack of long-term planning meant critical shortages remained.

Ultimately, the pandemic shows the importance of a strong domestic manufacturing sector to produce what Canada needs. It has also shone a light on the decline of Canadian manufacturing sector over the last number of decades.

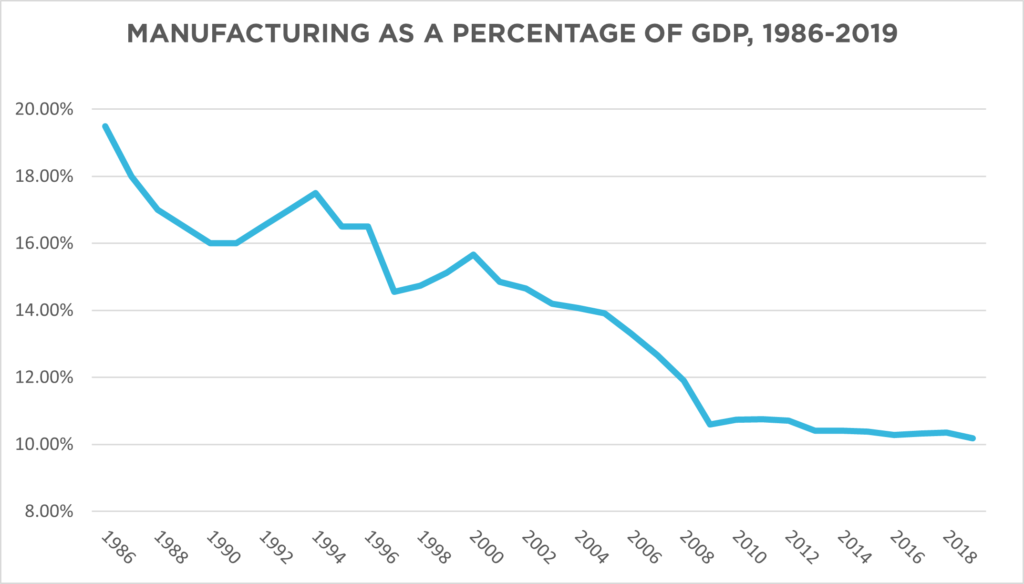

Over the past 20 years in Canada, GDP from industrial production has been essentially stagnant. Manufacturing accounts for roughly 10 percent of Canada’s GDP, down from about 16 percent in 2000,[2] and far lower than the high of 30 percent in the 1950s.[3] Indeed, it took the Canadian manufacturing sector close to six years to recover from the 2008-2009 financial crisis.[4] By contrast, Germany, a country with a domestic industrial strategy, has seen GDP from industrial production rise by more than 66 percent over the last 20 years, and its manufacturing sector rebounded from the 2008 crisis in fewer than three years[5].

Sources: Statistics Canada Table 36-10-0434-01 and The Canadian Manufacturing Sector, Adapting to Challenges; RBC Economics

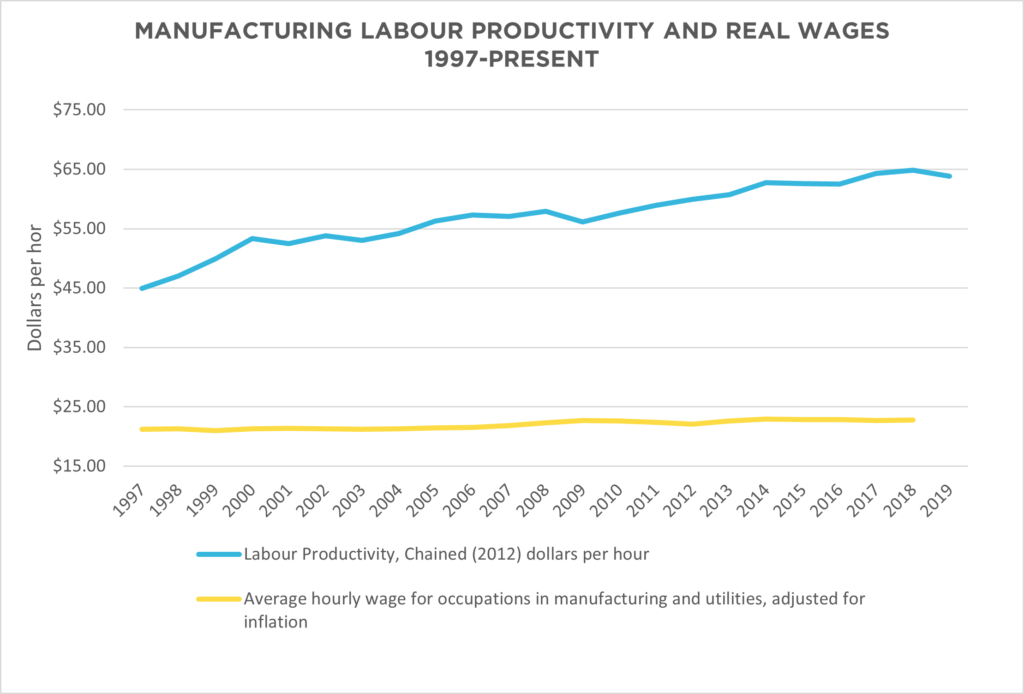

While labour productivity has increased[6], manufacturing’s share of the GDP, employment and wages have all stagnated or declined in some cases.[7]

Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0480-01 Labour productivity and related measures by business sector industry and by non-commercial activity consistent with the industry accounts and Table 14-10-0307-01, USW Research

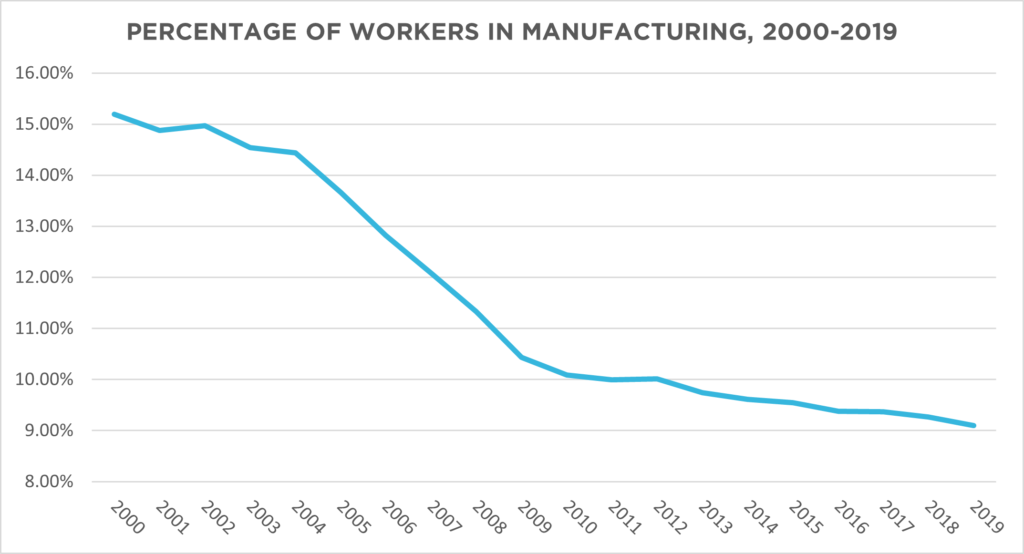

The decline in manufacturing has been a key contributor to the stagnation of wages in Canada, the decline in private-sector unionization, and Canada’s increasing reliance on the extraction and export of unprocessed natural resources. In 1980, almost 20 percent of all jobs in Canada were in the manufacturing sector. By last year, that had dropped to 9 percent.[8]

Source: Statistics CanadaTable 14-10-0023-01 Labour force characteristics by industry, annual

In short, the era of globalization and liberalized trade regimes has not been kind to Canadian manufacturing. While it is true that the pandemic has presented a challenge to a global economic order that is too often reliant on cheap labour and the prioritization of cheap goods and short-term gain, Canada cannot ignore the fact that it is still party to dozens of international trade and investment treaties and our manufacturing sector is still heavily reliant on export markets. Manufactured goods represent almost 70 percent of Canada’s total merchandise exports.[9]

Canada needs to be able to create and sustain a resilient manufacturing economy that will also be more competitive in a globalized economy. Successful manufacturing economies, such as Germany’s, have supported advanced manufacturing that creates good jobs and cannot be offshored to low-wage countries. Following this model requires rethinking the role that the state and workers can play in the revitalization of manufacturing.

This must start with the joint consideration of creating good jobs, while minimizing environmental impact. Policy decisions must be made with those considerations at the forefront. To go a step further, manufacturing strategies should also include explicit equity goals. The pandemic only exaggerated deep inequalities in the labour market along racial, gender and other lines.[10] The rise in service-sector jobs has not closed gender and racial wage gaps. Canada needs concerted training and apprenticeship policies that incorporate equity (including hiring and pay equity) and recognition of labour rights in procurement contracts and in investment decisions at various levels of government. Additionally, the country must invest in communities hit hard by de-industrialization and mine closures.

Overall, governments, working with the private sector and trade unions, must work to identify strategic and socially important sectors of the economy. The state should play a central role in co-ordinating, planning, regulating and allocating resources to important sectors, ranging from clean tech to childcare. Specific to manufacturing, federal and provincial governments must play key roles in determining, at the sectoral level, where to invest.

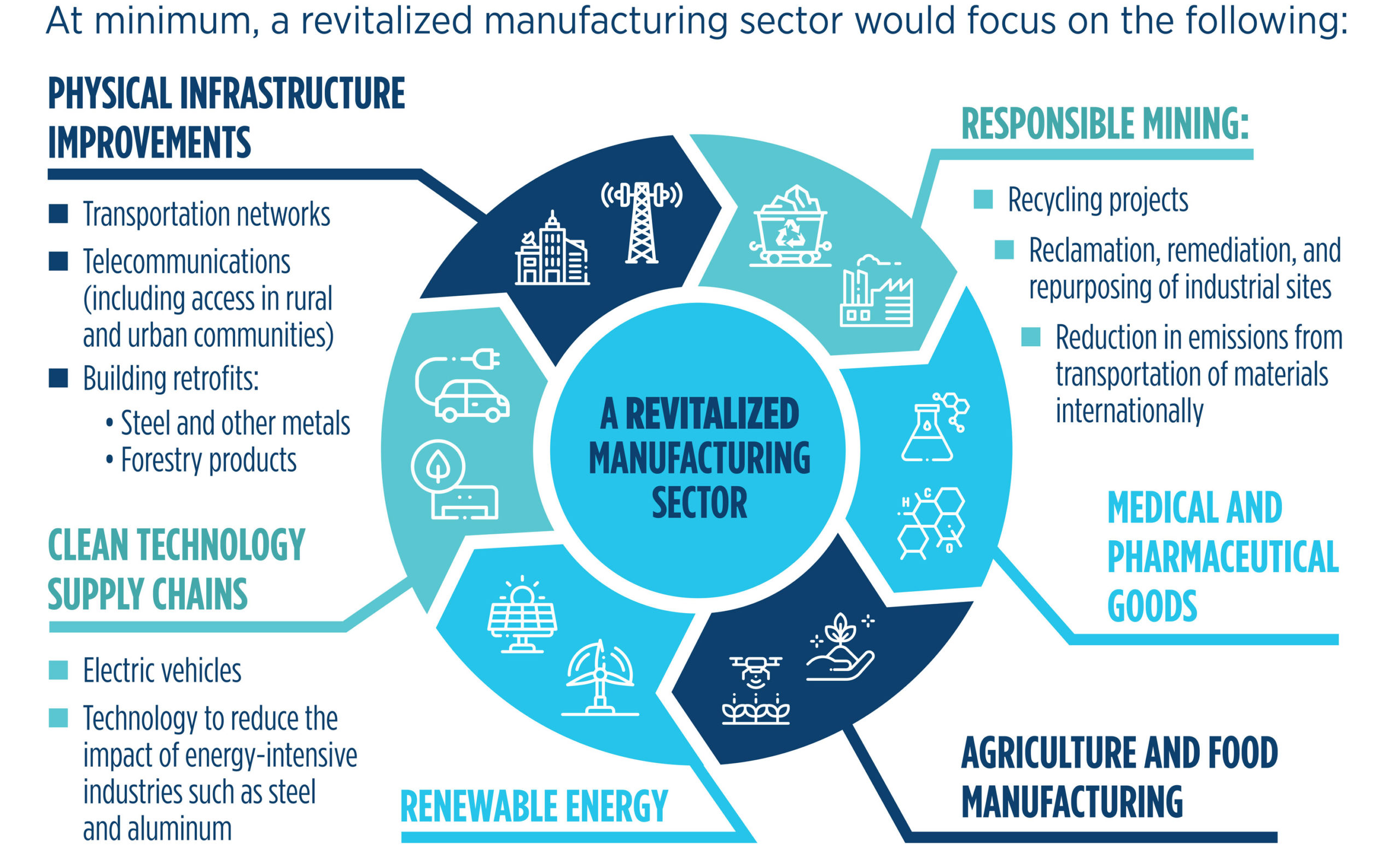

What types of economically and socially useful strategic industries should a manufacturing strategy involve?

From steel to clean energy to telecommunications, the old to the new, and from mined material to final product, Canada has the ability to co-ordinate its supply chains to produce the goods necessary for a clean, advanced economy.

Even many so-called intangible assets still have tangible components, from telecommunications infrastructure to mined material for digital devices.[11] Canada does not produce everything it needs, however it does have access to significant natural resources, many of which it exports for crucial value-added manufacturing. It is estimated that the total economic impact of Canada’s manufacturing sector is about four times the direct impact and that for every direct manufacturing job created, four additional jobs are created.[12]

The federal and provincial governments play key roles in ensuring the oversight and co-ordination of key industries and supply chains. This includes analysis of supply chains, including whether or not Canada can actually produce the raw materials needed for a final product. If so, are there areas in which the country has the opportunity for value-added manufacturing that it isn’t taking advantage of? Such has been the case with raw logs in British Columbia, where instead of creating good manufacturing jobs, large timber companies ship raw material abroad for processing. The negative labour and environmental consequences could be improved with proper planning, co-ordination and an explicit manufacturing policy.

In developing a national manufacturing strategy, the federal government should define made-in-Canada while considering the entire supply chain. Additionally, any broad manufacturing strategy should include life-cycle analyses and environmental impact assessments of mining, production and energy use. It is integral to assess the emissions impact of the transportation of products as well. For example, the Canadian Steel Producers Association estimates that using domestic steel reduces emissions from transportation by about one-third.

One of the fears of strengthening environmental standards — and of the possible increased cost of using Canadian-made goods — is that they will simply be undercut by cheaper imported products, rendering higher standards useless.

A comprehensive manufacturing strategy must include mechanisms such as border carbon adjustments (BCA) to prevent undercutting of strengthened environmental standards. A BCA would apply to goods produced in countries that have no form of carbon pricing, in particular on trade-exposed products with high emissions such as steel and aluminum. This would help to reflect the true cost of imported goods.

Where it really is not feasible to re-shore a supply chain (for example, there is no prospect for domestic production or Canada simply does not have the raw materials), then supply chain diversification is an option, instead of reshoring. Rather than relying on one country or one global supplier, Canada needs to ensure access to critical goods from multiple sources.

A manufacturing strategy must also require analysis of community impact, including the jobs and multiplier effects of reshoring supply chains and of public investments.

While there may be concern that concentration of industry will occur as a result of supply chain reshoring, the country must also consider current ownership structures where there is significant concentration, little to no Canadian ownership and owners who hoard wealth at the expense of investment and maintaining strong workers’ rights.

Ultimately, the nationality of owners is less important than ensuring Canada has mechanisms and policies in place that result in a good quality of life for workers. This includes strengthened bargaining power resulting in a more even distribution of wealth between owners and workers.

With the creation of good jobs at the forefront of a manufacturing strategy, it follows that Canada must ensure it has a properly trained workforce.

Government and employers have a responsibility to provide workers with training, apprenticeships, upskilling and reskilling. Federal and provincial government programs and agencies, including EI and ESDC programs, must be expanded to provide opportunities for training in strategic sectors, tied, where possible, to jobs guarantees.

Employers need to invest in the skills of their workforce, rather than shirking responsibility while complaining about a so-called skills gap. Unions can play a strong role in identifying where skills exist, including among retirees, and where gaps remain.

Union involvement is also critical when analyzing the real or potential impacts of automation. Automation and technological development is not inherently good or bad, but if the effects on employment, communities and environment are not considered, the potentially positive effects of automation can be lost. Technological advances must be tied to job protections for workers.

It is also essential to incorporate equity goals into training and apprenticeship programs, in procurement contracts and in funding and investment decisions. Strong workers’ rights, including strengthened organizing and bargaining rights are also a key component of this strategy. Public spending on clean technology and on infrastructure projects, for example, must support higher labour standards across the supply chain.

The current government has committed $180 billion in infrastructure spending from 2016 until 2028. In order to ensure that this funding is sufficient and effective in creating domestic jobs and in minimizing environmental impact, key changes are needed:

- Funding should be tied to a national manufacturing strategy;

- Canadian content must be defined; and

- Community benefit clauses with strong social and environmental criteria must be required.

Another consideration is a public infrastructure bank that would lend to governments at all levels, from municipalities to the federal government. A public bank could provide low-interest loans for public infrastructure projects of all types — social and physical. The recently created Canada Infrastructure Bank relies on significant private financing, which can increase costs, potentially doubling financing costs.[13]

Federal investments can also help sectors adhere to strong environmental standards. Identifying secure domestic markets for goods would help prevent a race to the bottom in terms of environmental and labour standards within Canada. High standards are frequently touted as trade barriers between the provinces: In an economy that centres on worker well-being and minimal environmental harm — with state support to achieve these goals — these so-called barriers may no longer be seen as such.

Upcoming provincial and federal budgets must not focus on austerity measures, rather governments must make strategic infrastructure investments that will create good, well-paid jobs and support short- and long-term economic development.

Private-sector investment is also an important component of a manufacturing strategy. However, the private sector has not been making the capital investments necessary to move towards a greener economy nor to bolster the skills of Canada’s workforce. Instead, it has been hoarding money. As effective corporate tax rates have fallen, investments in machinery have also fallen, from about seven percent in 1998 to 3.8 percent in 2018[14] and the money has instead stayed in private hands.

The problem is not that the money is not there, rather it is that it is not being used. Canada’s lost opportunities to invest in workers’ training and clean technology.

Tax reform, including modestly higher corporate taxes and cracking down on tax havens, would help ensure the ability to raise the funds needed for investments.[15] Federal and provincial governments cannot continue to heed the corporate-led argument that the lowest taxes will lead to the highest investment, yielding the best results for workers and the environment.

The federal government also plays an important role in investment in research and development, as well as co-ordination and marketing and it could also be a buyer. This is particularly important for pharmaceutical research and development for the public good. Investments can also play a strong role in the development and dissemination of clean technology and more energy-efficient technology for manufacturing and mining. Investments are also essential for strengthening telecommunications infrastructure and expanding access. Developing secure interprovincial transportation networks is also key to ensuring delivery and use of products across supply chains.

When it comes to ensuring markets for goods produced in Canada, one of the most promising means of augmenting demand for domestically manufactured products is to tie in sustainability goals into procurement policies. Targeting investments in sectors with “high potential for economic stimulation, job creation and environmental transformation,”[16] government purchasing and procurement contracts must be one of the first mechanisms used towards the goal of revitalizing Canadian manufacturing.

While procurement policies that contain explicit local employment or material provisions may come under attack through the WTO, under the General Procurement Agreement, or the CETA, sustainability measures are much less likely to be challenged.[17]

Canada must include clear environmental and social commitments, including community benefits in procurement for federal, provincial and municipal contracts.

Another strategy, recognizing our interdependence with U.S. markets, is to further develop North American markets using Buy Clean[18] procurement policies in both countries. Despite the lack of procurement policies in the CUSMA, Canada should work with U.S. allies to ensure a binational strategy for North American manufacturing.

A revitalized manufacturing sector can play a key role in Canada’s post-pandemic recovery. However, Canada cannot rely on the old mechanisms, such as offshoring or ever-expanding export markets, for the goods it does produce. This requires a change in thinking about the role of the state and of workers in revitalizing Canadian manufacturing and, ultimately, directed policies that promote good jobs, to benefit communities across the country, while reducing environmental impact.

Already, nations around the globe are rethinking the place of manufacturing in their domestic economic strategies to ensure access to essential goods and bolster decent employment. If Canada does not use this opportunity to rethink the role of manufacturing in our economy, it risks being left behind in a changing international economic order.

REFERENCES

- Blake, Cassels and Graydon, LLP. April 21, 2020. Canadian Procurement Policy and COVID-19: Comparing Approaches. ↑

- Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0434-01 Gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, by industry, monthly. ↑

- RBC Economics. February 2017. The Decline of Manufacturing’s Share of Total Canadian Output – A Source of Concern? ↑

- https://tradingeconomics.com/canada/gdp-from-manufacturing ↑

- https://tradingeconomics.com/germany/gdp-from-manufacturing ↑

- Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0480-01 Labour productivity and related measures by business sector industry and by non-commercial activity consistent with the industry accounts ↑

- Morissette, Rene. Jan. 15, 2020. The impact of manufacturing decline on local labour markets in Canada. Statistics Canada found that a decline in manufacturing employment led to an overall decline in men’s real weekly wages in areas hardest hit by manufacturing decline. Women’s wages were not as heavily affected by manufacturing decline. Women’s average earnings remain lower than men’s regardless of sector. ↑

- Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0023-01 Labour force characteristics by industry, annual. ↑

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada ↑

- Statistics Canada. August 2020. Labour Force Survey.0 ↑

- Hund, Kristen et al. World Bank. 2020. Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition. ↑

- Canadian Exporters and Manufacturers. Manufacturing, Growth, Innovation and Prosperity for Canada. ↑

- Sanger, Toby. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. . Creating a Canadian Infrastructure Bank in the Public Interest. ↑

- Sanger, Toby. Canadians for Tax Fairness. Jan. 7, 2020. Decades of tax cuts have given corporate Canada plenty to celebrate. ↑

- For additional information on tax reform and cracking down on tax havens, see: Sanger, Toby. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Nov. 1, 2019. Time to step up for tax justice: Important reforms to end tax-dodging and tax havens are on the horizon. Why isn’t Canada doing more? ↑

- OECD Report for the G7 Environment Ministers. June 2017. Employment Implications of Green Growth: Linking jobs, growth and green policies. ↑

- For additional information on the possibilities from green procurement, see: Cassier, Lisbeth. International Institute for Sustainable Development. 9. Canada’s International Trade Obligations: Barrier or opportunity for sustainable public procurement? Unpacking Canada’s WTO GPA and CETA commitments in relation to sustainable procurement. ↑

- Bluegreen Alliance. . Bluegreen Alliance sets out an American strategy for manufacturing revitalization. ↑

PARTNERS

Private Sector Partners: Manulife & Shopify

Consulting Partner: Deloitte

Federal Government Partner: Government of Canada

Provincial Government Partners:

British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario & Quebec

Research Partners: National Research Council Canada & Future Skills Centre

Foundation Partners: Metcalf Foundation

PPF would like to acknowledge that the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the project’s partners.