The Unclaimed Middle Ground Between Unrestrained Fiscal Spending and Unreasonable Restraint

by Frances DonaldThe COVID-19 recession has ushered in near-historic levels of government spending, in Canada and abroad. But as the economy has shown green shoots of recovery, the conversation has quickly — too quickly — pivoted in some quarters to the dangers of rapidly rising government debt.

Just as households and businesses have to pay regular interest payments on their borrowed debt, so, too, does the government.

When the government spends beyond its revenue, it must borrow from domestic or foreign investors by issuing bonds. Just as households and businesses have to pay regular interest payments on their borrowed debt, so, too, does the government.

And, also like households and businesses, it is the debt servicing costs — like mortgage payments — as opposed to the total level of debt that eats into spending. Economists generally fear that higher debt levels will eventually be subject to a sharp rise in debt servicing costs, limiting a government’s ability to spend and therefore restraining future growth.

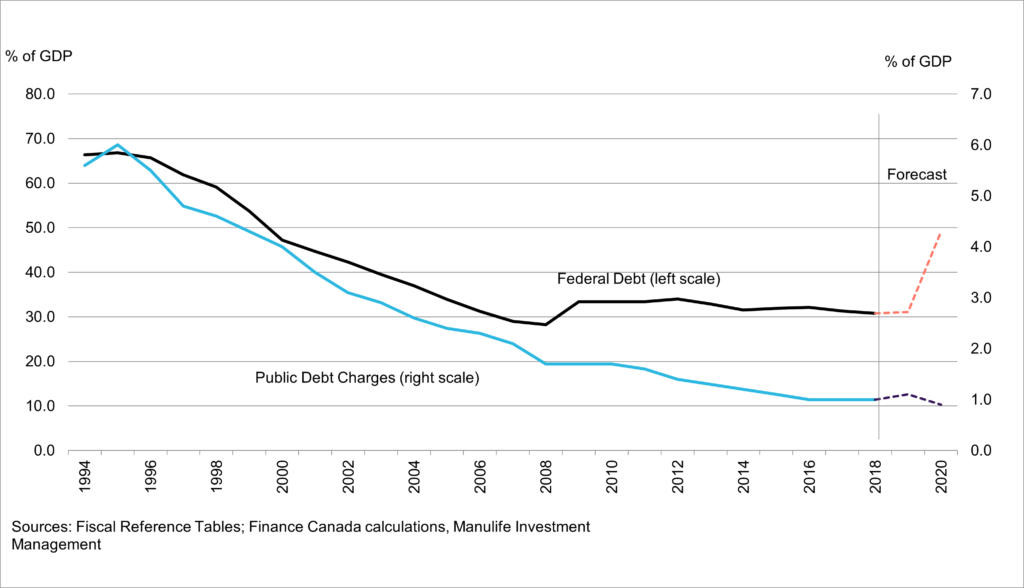

These concerns are not just theoretical in nature. Canada experienced the painful lessons of high government debt in the mid-1990s, when total federal net debt to GDP rose to 67% and debt servicing costs took up over 35% of revenues. This ushered in a period of fiscal austerity and painful spending pullbacks.

Fast-forward almost 20 years and Canada’s federal debt is now on trend to hit nearly 50% of GDP with additional spending certainly capable of pushing the figure much closer to its mid-1990s peak. And yet, thanks to a simultaneous drop in interest rates, the cost of debt has not risen at all. The Department of Finance expects public debt charges will actually decline from 1.1% to 0.9% of GDP even as the extent of debt rises.

So what’s the worry? Proponents of fiscal restraint make the point that interest rates will eventually rise and warn that Canada could end up back in its 1990s predicament, lose the confidence of foreign investors, see the cost of debt skyrocket, and be forced into a period of painful austerity involving either higher taxes, less spending, or both.

But 2020 and the decade that follows are more likely to usher in a new paradigm in government spending. Among its characteristics are the willingness of central banks to serve as lenders of first resort to governments, more than a decade-long record of low interest rates co-existing with modest inflation, the changing profile of inflation targeting and the fact that no matter how high debt may go, Canada is almost certain to look relatively attractive to international investors compared with even more highly indebted alternatives. This is not the 1990s. Even the vexing question of fiscal anchors is no longer as vexing as it may seem.

This time may actually be different as these factors substantially reduce the probability of Canada facing a debt crisis over the next 10 years. They don’t collectively amount to a permission slip to spend without regard for future risks, of which there are still many. But they imply that there’s a longer runway than usual for governments to (a) stem the ongoing crisis (b) consider longer-term, productivity-enhancing growth strategies, and c) resist the pressures to resort to austerity.

Put differently, premature fiscal restraint that stymies either short-term or longer-term growth may not only be unnecessary but may ultimately be a greater risk to Canada’s economy than a rise in debt-servicing costs.

A new middle ground has opened up between unrestrained spending and unreasonable restraint, and it’s that middle ground that can provide Canada with the best of both worlds.

Federal Debt and Public Debt Charges

There are three primary ways that the debt servicing cost can rise for governments.

- Central banks can hike policy rates which increases the cost of borrowing for everybody, including the government.

- Should global investors become concerned that Canada is a riskier country for lending, they can demand higher interest rates or force a restructuring of Canadian debt, pushing up the costs of borrowing (and often weakening the currency at the same time).

- The total amount of debt can increase, effectively implying the government has taken out a larger loan and, even as the interest rates remains stable, the total costs of debt rise.

What the middle ground approach to fiscal spending recognizes is that the first two of these traditional concerns are far less likely to be problematic than in past cycles.

Central banks, including the Bank of Canada, are likely to keep rates low for substantially longer than in past cycles.

It took seven years following the 2009-09 financial crisis for global central banks to begin sustainably normalizing policy rates. But even after achieving a liftoff in rates, no major central bank was able to effectively normalize interest rates before the cycle neared its end. The Federal Reserve only attained a policy rate of 2.5%, less than half the peak policy rate of the prior cycle (5.25%), while the Bank of Canada reached 1.75%, far below the 2007 peak of 4.25% and a distant cry from the 8% policy rate of the mid-1990s.

There is a long list of reasons to believe that raising interest rates in Canada, and globally, will be just as, if not more, lengthy and challenging than in the period following the financial crisis. These include even higher levels of debt, deteriorating demographics, and a both cyclically and structurally weakened economy that will likely take years to return to pre-COVID-19 levels of activity.

In addition, central banks are likely to want to begin normalizing their balance sheets and other forms of unconventional policy before raising policy rates, just as the Federal Reserve did in 2015. That will be a tall task given that balance sheets are multiples larger than they were at their peak in 2009 and there are significantly more central banking tools at play than during that crisis, particularly in Canada.

Finally, central banks, including the Federal Reserve and likely soon the European Central Bank are migrating towards an ‘average’ inflation targeting framework in which they seek to overshoot the traditional 2% inflation target in an effort to ‘average’ 2% inflation over a more extended period of time. This implies that even traditional inflationary pressures will be a less likely catalyst for higher rates than in past cycles.

Central banks on hold for an extended period carries two important benefits. First, it implies that the rate being charged on government debt will likely remain extraordinarily low for several years. Second, it implies that growth rates are more likely to grow at a faster rate than interest rates. As David Dodge explained in his paper in this series: “If growth goes up at a faster rate than interest rates, then we should be fine. If interest rates go up faster than growth, then we are in trouble.” Indeed, central banks will most likely be positioned to support an environment in which growth is rising faster than interest rates.

The Bank of Canada is a captive buyer of Canadian government bonds.

One of the game changing policy developments of the COVID-19 recession has been the BoC’s launch of its first large-scale asset purchase program. This policy involves purchasing bonds issued by Ottawa (Government of Canada securities), among other securities, in an effort to provide liquidity to the markets and also to suppress interest rates across the yield curve.

The Bank has so far been successful at attaining both of these goals, but its effort carries an additional implication: between March and September, it bought 83% of the Government of Canada’s bond issuance. By mid-September, the Bank owned 30% of the Canadian government bond market, up from 14% before the crisis. By the end of 2021, it is expected to hold almost 60% of the market.

Fairly suddenly, the federal government is not in a position where it has to entice foreign investors to buy its bonds or fear their demand for higher rates. Instead, it has a captive, domestic buyer which is actively trying to reduce rates.

Yes, eventually, the Bank will choose to taper its bond buying program. But we are likely several years from that process. Moreover, the U.S. experience with an attempted reduction of its holdings of U.S. Treasuries suggests any normalization is likely to be slow and far from complete.

Foreign investors are not monitoring Canadian federal finances in isolation, but in terms of relative attractiveness to other major economies.

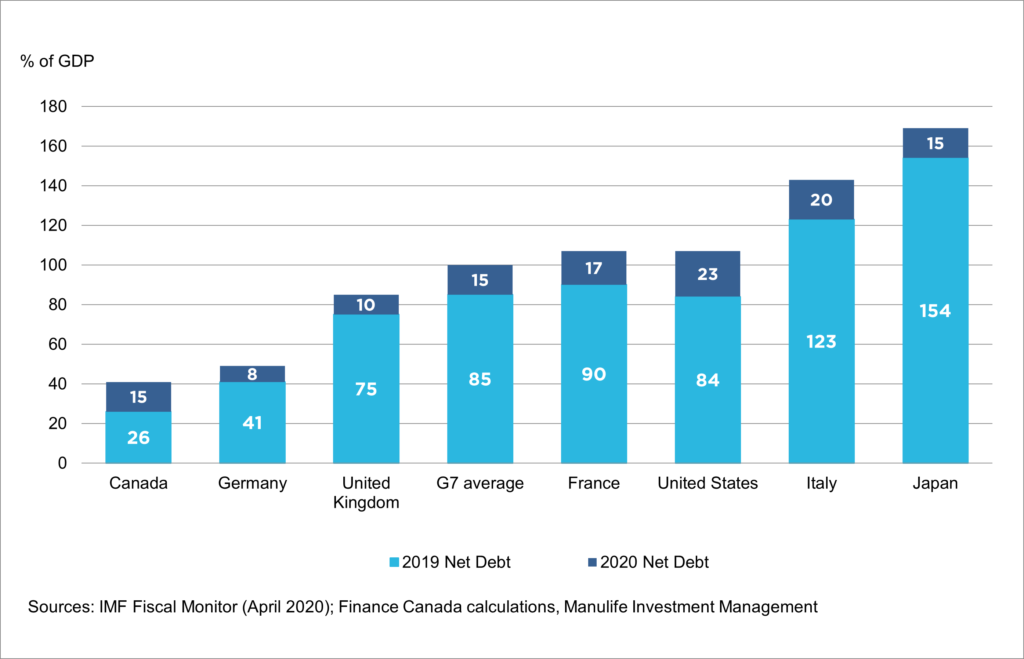

Critically, foreign investors do not monitor Canadian assets in absolute terms — the financial universe is a relative one. For investors to leave Canadian bonds, for example, Canada’s fiscal position would have to deteriorate relative to its global peers. Even though Canada has had one of the largest year-over-year changes in its fiscal position, it is likely to remain in a stronger relative condition to its G7 peers, rendering it still more relatively attractive in the government fixed income space. Indeed, the COVID crisis hit all global economies, prompting fiscal responses from all major economies — Canada has not acted in isolation and the near-historically large ramp up in spending is not unique to the Canadian experience.

Canada carries additional advantages that reduce the likelihood of mass investor flight: it is still offering a positive yield, whereas every other G7 economy, except the United States, has negative yielding debt. Most interestingly, Canada is currently only one of two S&P AAA-rated sovereign debts that is carrying a positive yield.

G7 General Government Net Debt, 2019 and 2020

The above factors suggest low and sustained debt servicing costs provide plenty of runway and, importantly, substantially more than past cycles. But that runway is not endless. Eventually, central banks will attempt a normalization of interest rate policy with both policy rates and their balance sheet, and Canada cannot pursue spending to the extent that its fiscal position dramatically deteriorates relative to its peers.

There is a middle ground between advocating for spending without restraint and demanding a near-term balanced budget. That middle ground involves three key focuses: long-term growth generation, fiscal responsibility and recovery encouragement.

1 Growth focus

First, in keeping with the idea that growth must rise faster than interest rates, the focus must be on productivity enhancing, growth-generating spending. Other papers in this series will make their arguments as to what those spending priorities should be. Certainly, any credible plan in the wake of the COVID learning experience must include improved day care, a restoration of immigration flows (which was a critical pre-pandemic growth driver) and long-needed attention to competitiveness and tax policies. Global investors will be attracted to policy choices they view as most effective on these fronts.

2 Rethinking fiscal anchors

Second, as many have argued, a fiscal anchor will eventually be needed, if only to appease concerned parties that the fiscal position is being prudently monitored. However, it’s time for Canada to think beyond the traditional fiscal anchor to one or more that incorporate previously mentioned shift in the interest rate outlook and the developing role of central banks as buyers of government securities. For example, some have suggested a commitment to reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio or spending caps, but these do not take the cost of debt into consideration, and are challenging to get right given extraordinary uncertainty about the length of this recession and thus, the size and scope of necessary spending and borrowing A commitment to keeping debt servicing costs to a set share of GDP is a better approach. However, it problematically links monetary policy to fiscal policy too explicitly. This can complicate the independent role of the Bank of Canada by upping the ante to the government of any interest rate hike, heightening potential political pressure or certainly increasing the fiscal and political consequences of any moves.

One idea that deserves additional consideration in the context of a deep recession that necessities spending in a low cost environment is the approach taken by the province of Quebec, explained by economist Marc Levesque here. Quebec’s fiscal commitment involves balancing its budget over the full economic cycle, implying large spending when the economy is weak and restraint and savings while the economy is strong. This approach is well suited to a recession whose length is difficult to measure and avoids arbitrarily limiting spending while it is still needed.

It does, however, ask that debt not be accumulated in good times, helping to maintain the perception of fiscal responsibility. The approach likely also has the benefit of maximizing fiscal multipliers, or, put differently, the efficiency of government spending. And, it works in tandem with monetary policy as opposed to being explicitly linked to decisions made at the Bank of Canada.

3 Immediate recovery as a priority

Finally, while it’s tempting to develop spending programs that focus on long-term changes in Canada’s growth outlook, the priority should be to dampen the immediate recession and encourage a swift recovery. We cannot be so focused on building back stronger that we forget our house is still on fire. Canada remains in the midst of its worst recession in modern history, with extremely elevated unemployment and widening income, racial, and gender disparities.

- Short-term spending programs geared towards the two to five-year horizon help smooth over some of the problems with increasing debt too aggressively, even in the context of low debt servicing costs.

- Markets have generally rewarded countries that front load spending to dampen the immediate effect of the crisis. Neither currency nor bond markets have been penalizing countries for paying for the pandemic. Indeed, the opposite has been true and the lack of fiscal action to support near-term growth in some countries has spurred risk-off events and widespread concern.

- Shorter-term spending agendas provide for more policy flexibility than long-term commitments and this carries particular value in an environment of extreme uncertainty.

- Shorter term spending is less likely to result in downgrades from credit agencies. Canada has maintained its AAA rating from key rating agencies such as S&P and Moody’s. Fitch downgraded Canada from AAA to AA+ because it feared Canada’s longer-term positions, not the short-term needs of the recession. As the S&P wrote: “We expect a deterioration in fiscal and debt metrics in Canada because of the size of the government’s unprecedented stimulus policy. However, Canada’s public finances were well-positioned entering the pandemic to enable a strong policy response to contain the negative impact without deteriorating sovereign creditworthiness, despite a substantial rise in the government’s debt burden.”

- Shorter-term spending can be associated with shorter-term issuance, that is, government of bonds issued in the five to seven-year space. In Canada, this is critical as provincial bonds are typically issued at the 10-year and 30-year maturity and competition from federal bonds could crowd out demand for provincial borrowing, hampering provincial spending.

COVID-19 has ushered in the worst economic crisis in modern history. It has changed the nature of work, our relationships with trade partners, perceptions around the importance of childcare and so much more. It has also changed the fundamental dynamics behind federal fiscal health. This must be acknowledged.

The problems of the past are not the problems of the future, and the frameworks we formerly used to understand the consequences of government debt must change. And while there will be those who continue to stress the importance of large-scale spending as well those who call for fiscal restraint, we should remember there is a middle ground. That middle ground may not grab as many headlines, but it’s likely to be the best approach for Canada’s future.

PARTNERS

Private Sector Partners: Manulife & Shopify

Consulting Partner: Deloitte

Federal Government Partner: Government of Canada

Provincial Government Partners:

British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario & Quebec

Research Partners: National Research Council Canada & Future Skills Centre

Foundation Partners: Metcalf Foundation

PPF would like to acknowledge that the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the project’s partners.

Disclosure

A widespread health crisis such as a global pandemic could cause substantial market volatility, exchange trading suspensions and closures, and affect portfolio performance. For example, the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has resulted in significant disruptions to global business activity. The impact of a health crisis and other epidemics and pandemics that may arise in the future, could affect the global economy in ways that cannot necessarily be foreseen at the present time. A health crisis may exacerbate other pre-existing political, social and economic risks. Any such impact could adversely affect the portfolio’s performance, resulting in losses to your investment. Investing involves risks, including the potential loss of principal. Financial markets are volatile and can fluctuate significantly in response to company, industry, political, regulatory, market, or economic developments. These risks are magnified for investments made in emerging markets. Currency risk is the risk that fluctuations in exchange rates may adversely affect the value of a portfolio’s investments.

Read More / Veuillez en lire plus