Two Mountains To Climb: Canada’s Twin Deficits and How to Scale Them

by David DodgeThe 2020 COVID-19 crisis has produced a unique economic emergency layered on top of a decade-long build-up of pre-existing weaknesses. One cannot be addressed in isolation from the other.

The 21st century began well for Canada. Our fiscal turnaround had proven durable as our debt-to-GDP ratio moved steadily downward. We were running a current account surplus with the world on the backs of strong demand and good prices for our exports and net inflows of foreign direct investment. We were building our net worth as a nation and setting the stage for future growth through the creation of new economic capacity. As a result, jobs and income were on the rise, along with opportunity.

But the situation began deteriorating in the second decade of the new century. The current account, a broad measure of our trading and investing relationship with other nations, turned negative and remains there. Non-energy exports never recovered after the Great Financial Recession and the tide turned against investment in Canada following the 2015 oil price collapse. In the long run, the real income of Canadians and the public programs they cherish depend on the value of the goods and services (GDP) Canadian workers and businesses produce. We maximize their impact by exporting those in which we are most cost efficient and importing those where we are less efficient.

Long before COVID-19, however, the signals were straightforward and stark: Canada’s industries were losing ground in global competitiveness and attractiveness to foreign investors. Even Canadian businesses and individuals were finding more appealing places to invest. We were no longer building our future at home, but rather collecting rents in the present on investments from the past, like coupon clippers living off past prosperity.

Today, policymakers are being called upon to address these pre-COVID economic and policy weaknesses alongside brand new pressures introduced by the crisis—the explosion in public debt, heightened demands for social security and health care and, leaving aside long-term climate pressures for the moment, the further erosion of the price for our largest export category by far, crude oil and bitumen.

It is more incumbent than ever for governments to know where they are headed overall, and to communicate effectively with citizens, markets, global trading partners and investors about how we intend to get there. If Canada is to fully recover from the COVID crisis, we need to articulate and promote a medium and long-term plan to restore ourselves as a favoured destination for investment and to use that investment to enable forward-looking industries and entrepreneurs to make and sell what the rest of the world wants to buy from us. This is the way to enhance the standard of living for Canadians.

The messages of this paper are very simple:

- You can’t eat what you don’t produce, and the value of what we are producing as a country is not covering what we are consuming. We can continue along that way for a while, but it is not a sustainable proposition.

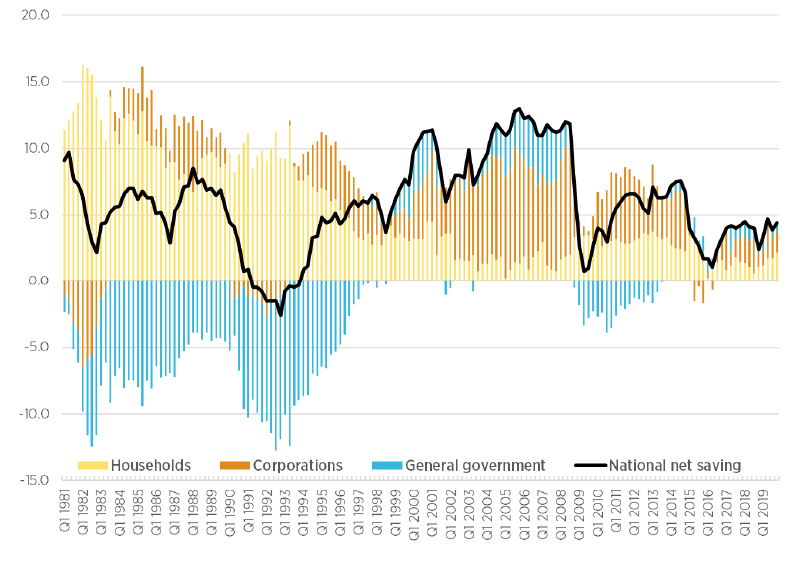

- You need to invest today to produce more and better in the future. Over much of the past decade, we have been investing less in our future while consuming more in our present, as evidenced by our lower net national savings rate (Figure 1). The COVID crisis exacerbates those trends.

Figure 1: Net Saving as % of National Disposable Income | 1981Q1 to 2019Q4

Source: Statistics Canada, table 36-10-0111-01.

- You want to produce where your value is greatest. We need to add greater value to what we produce and, to the extent we are moving away from our biggest export, oil, we need to find competitive replacements that are attractive to buyers abroad and secure access to those markets.

- You need greater productivity increases to compensate for an aging population. As our population ages, the growth of our labour force slows—and so doesn’t provide our historic natural growth of output. In order to preserve our living standards and quality of life, we need to maintain high immigration levels and ensure faster productivity gains.

Ultimately, this paper is optimistic in seeing in the COVID crisis the shock we have needed to muster the attention and will to address our weakening economic base. Over the past decade, the Canadian economy has been like the proverbial frog in the pot of water, never really feeling the gradually rising heat and therefore failing to react proportionately. The COVID crisis represents a sudden rise in temperature.

It is not too late for Canadian policymakers to get this right and bend the future more definitively in the favour of Canada and Canadians. This paper sets out some thoughts on how this can be done.

Most attention to the economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis has been devoted, not inappropriately, to Canada’s burgeoning fiscal deficits and the labour market insecurity of Canadians. While one may quibble with this measure or that, a robust government response to an unprecedented crisis was absolutely necessary—and so we will have to determine how to distribute the burdens of this debt over time and among different segments of the population.

There is a second deficit that also merits serious public attention. Canada’s current account provides a reliable reflection of the medium-term strengths and weaknesses in the economy. The current account represents the sum of Canada’s economic interactions with the rest of the world—imports and exports of goods and services, payments to foreign holders of the country’s investments against payments received from investments abroad and transfers such as foreign aid or remittances. The current account can be in deficit for a time without problem. During an economic expansion, for instance, Canadian purchases of capital and consumer goods from abroad may rise.

But a chronic current account deficit that never corrects, particularly in times of global economic uncertainty, eats away at the confidence of foreign lenders and investors, sometimes resulting in sudden plunges in the value of national currencies and the rise, in response, of domestic interest rates—something Canada experienced in the mid-1990s and can ill afford today.

Throughout most of the 20th century, Canada was a “capital short” economy. We were able to grow our output from capital-intensive industries by being an attractive destination for foreign investment. Growing our exports of goods allowed us to service these foreign capital inflows and thus to maintain access to global capital markets on favourable terms. Canadians were well served by this balance in our economic relations with the world.

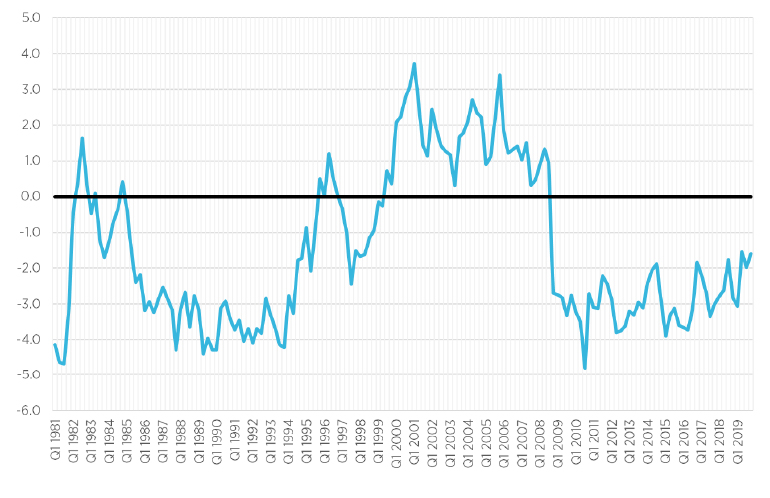

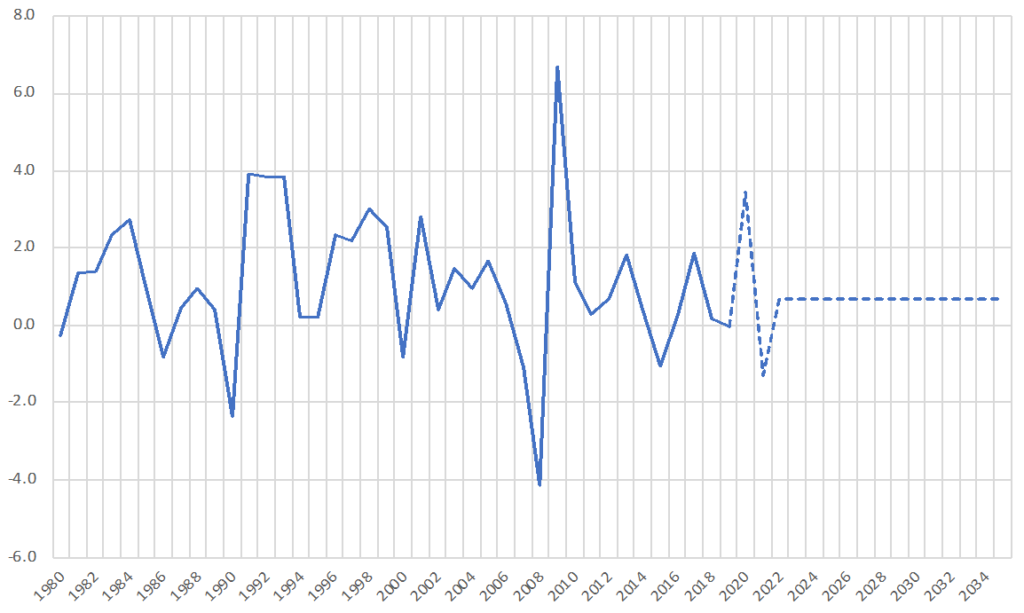

In the years before the 2008 financial crisis (see Figure 2). Canadian goods exports exceeded imported goods by a healthy 3-5% of GDP, of which the first three percentage points were attributable to net energy exports. The latter were enough to offset net imports of services and consumer goods as well as a net outflow of interest payments on government and corporate debt, a positive trend line that lasted through the early years of the 21st century. (See Appendix A).

Figure 2: Canadian Current Account Surplus (+) / Deficit (-) as % of GDP

Source: Statistics Canada, tables 36-10-0121-01 and 36-10-0104-01.

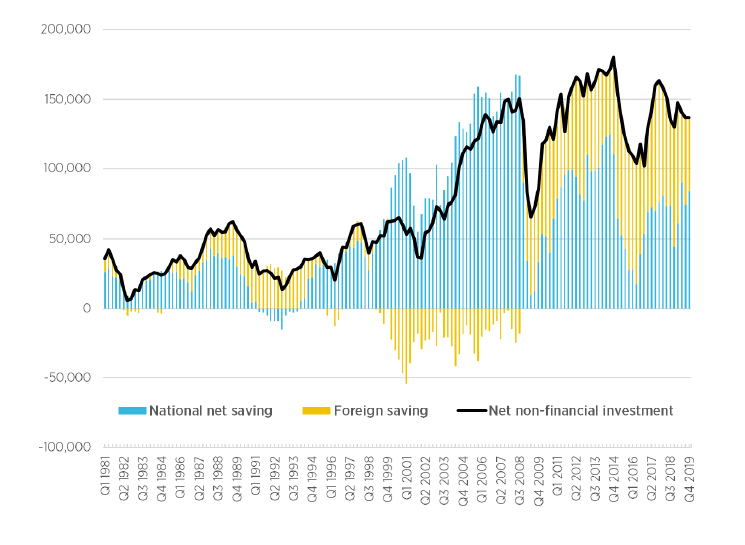

Going into the COVID crisis, however, Canada’s current account had deteriorated significantly. We have been recording annual current account deficits with the rest of the world of between 2% and 3% of GDP, an approximately $50-$60 billion shortfall every year. Even though Canada fared relatively well in the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09, net exports of non-energy goods, including motor vehicles and parts, declined sharply in the aftermath from about 2% of GDP to minus 4%. The deficit in services also worsened as did the flow of direct investment into Canada, especially into the oil and gas sector. By the time the pandemic hit, Canada had recorded 11 consecutive years of current account deficits as we borrowed from foreign savers to make up for the shortfall of domestic savings to finance capital investment. [see Figure 3] The current account deficits can also be seen as the inevitable product of Canadians and their governments choosing to borrow to maintain a high level of private and public consumption rather than finding ways to generate national income through added production.

Figure 3: Saving and Investment in Canada ($m)

Source: Statistics Canada, table 36-10-0111-01.

Oil was one of the few export sectors that held up well, despite little access to offshore markets and a lack of bargaining power with U.S. refineries, which extracted a discount below the world price.

In 2019, our energy sector nonetheless contributed a net $76.6 billion to the current account, largely covering net consumer imports ($55 billion) autos ($22 billion) and travel services ($11 billion). Of the energy contribution, some 80% came from crude oil and bitumen. Adding natural gas brought the share above 90%. Coal was third, electricity fourth. Fossil fuels and other resources held the economy aloft, particularly through the 2008-09 recession, a reality that for now remains intact and therefore that we must accept even as we transition away from them. Too abrupt a move will generate painful shocks to the overall economy.

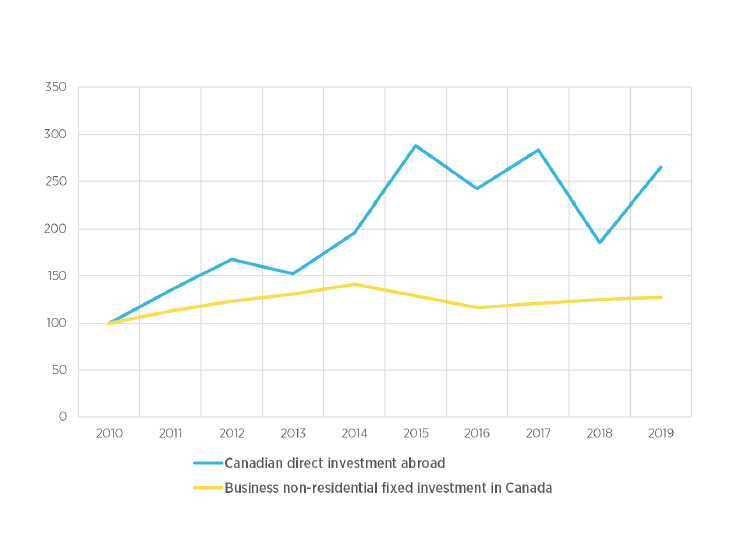

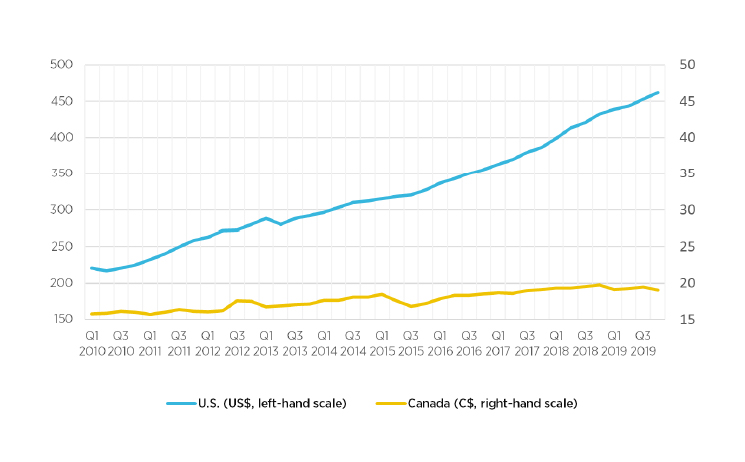

Direct foreign investment in the oil and gas sector has also fallen off. Even domestic Canadian firms are increasingly choosing to build businesses elsewhere in the world. [see Figure 4] By the end of 2019, Canadian direct investment assets abroad at market value outweighed foreign direct investment into Canada by $804 billion, almost all of that built up since 2012.

Figure 4: Canadian Investment in Canada and Abroad | 2010 = 100

Source: Statistics Canada, tables 36-10-047-01 and 36-10-0104-01.

In the wake of COVID-19, households and businesses—not just governments—will have much more debt to service in 2022 than they had in 2019—with little extra productive capacity—meaning little growth in incomes—to enable them to do so. Despite low interest rates, the cost of servicing debt securities held by non-Canadians amounted to $47.3 billion in 2019. With Canada’s stock of public debt set to grow at the federal level by perhaps $500 billion this year (and almost $100 billion for provinces) and oil destined to bring in less revenue, the current account deficit will be under yet further pressure.

It is important to note that not all our borrowing is being sourced domestically, as it is sometimes supposed. Foreign investors acquired an all-time record of $54 billion in Canadian debt securities in April alone. They followed that up with another $32.4 billion in May, the second highest total since monthly data began being compiled in 1988, followed by net sales of $7.8 billion in June.

Should these purchasers of our debt at some point grow nervous about our economic prospects, history shows they could demand the additional protection of foreign-denominated loans or higher interest payments. This would place downward pressure on the Canadian dollar, raise the cost of imports across the board for Canadian consumers, including the purchases of production-enhancing capital equipment for businesses.

Significant current account deficits and the trend in net outflows of domestic investment cannot continue indefinitely without extracting a cost. The rest of the world will not go on investing in Canada unless risk-adjusted returns here are as high or higher as they are elsewhere. Nor will foreigners continue to absorb Canadian corporate and government debt—especially debt issued in Canadian dollars—if the weakening of federal, provincial, and corporate balance sheets persists. If Canadian governments continue to borrow from the world to finance consumption, they will eventually encounter increased resistance from lenders. We are already seeing a debate breaking out in the form of conflicting credit ratings for Canadian debt. This may be followed at some sudden future moment by demands for interest rate premiums, decreased ability to borrow in Canadian dollars and the exclusion of weaker corporate and provincial creditors from the market.

Unless governments adopt credible plans to rein in borrowing (either through expenditure cuts, tax increases or a persuasive growth plan), lenders could eventually force a restructuring of our debts, as we saw in Asia and Russia in 1997-98, and in peripheral Europe in 2014-15 and are witnessing again today in Argentina.

We will return to the permutations in the third section of the paper. Suffice to say, Canada is not yet anywhere close to keeping that company, and is in relatively better fiscal shape than many of its peers. But the weaker current account position after 2006 reflects, in part, long-standing competitiveness challenges for Canadian industry that will need to be aggressively addressed in the post-COVID world while also having to contend with weaker global demand.

At a time when the COVID crisis will be requiring the generation of additional wealth in order to cover the burden of new public debt, we can hardly afford to surrender any level of investment in productive capacity. We need to address these hazards by restructuring our economy and, through domestic policy choices, expanding our capability to supply the kinds of goods and services the world seeks and is prepared to purchase from us.

Nothing about the current account crunch should detract from the critical importance of also bringing our fiscal balance back under control. The necessity to regain a sustainable fiscal position is rooted in issues of both economic welfare and social fairness. Rising debt and its service costs will, over time, crowd out spending on more economically and socially productive uses. Between the 1994 and 1995 federal budgets, debt service costs soared by more than $5 billion, about half from rising interest rates and half from an increased stock of debt. That was worth one CBC, one Via Rail and all of Ottawa’s post-secondary expenditures and veterans’ allowances. If we are not careful, something similar could happen again.

Perpetuating the financing of current consumption over future investment also raises issues of inter-generational equity by imposing the debt burden on younger Canadians. And it risks ultimately leading to higher interest rates, a huge potential load for highly indebted governments, corporations and households. Canadian policymakers will have to come to grips with how they are going to distribute these burdens over time and over different segments of the population. In other words, who pays the price, how big a price and when.

The even more important issue right now is how we use our borrowing. The challenges of distributing the debt burden will be far more manageable if there is less burden. And that will require directing spending to create greater productivity and growth to generate higher revenues to governments (as well as households and businesses), thus keeping the debt-to-GDP ratio in check.

At the end of 2019, I projected that Canadian growth would continue to deteriorate from its relatively good 2018 performance. In providing a jolt of short-term stimulus, the 2017-18 Trump tax cut gave our exports a lift as well. But the effects were fading by last year. I forecast that, at best, productivity gains would amount to 1% per annum. Real output would only have increased 1.7-1.8% per annum in 2020 through 2022 and potential growth would have declined slightly thereafter as a result of declining employment/population ratios. I was pessimistic about the ability of Canadian corporations and governments to introduce productivity enhancing digitization measures, especially in the service sector. Progress on steadily bringing down federal debt-to-GDP ratio had effectively stopped by 2019, because federal government borrowing for consumption purposes had begun to increase, but even more importantly because the rate of growth of GDP had slowed again.

Such was the situation when COVID struck. The expectation of a 1.8% growth benchmark in 2020 was sobering enough before the crisis. Now, once a sustained recovery takes hold, it would simply be too little and would have to counter the headwinds of a destabilized economy, export markets that are less open, interruptions to our immigration pipeline, supply chains in need of redesign and, of course, the spike in public debt. Coaxing more growth out of the economy has gone from a major policy challenge to an absolute necessity.

So what is to be done?

We need to capitalize on the opportunities presented by our domestic adaptation to COVID and by COVID-induced changes in global demand to reset our strategies for boosting the value-added sectors of our domestic production and by raising productivity. This will require Canada to move swiftly and with determination to enhance digitization of our domestic production processes for both goods and services. And we need to move equally swiftly to dramatically increase investment in human, physical and intellectual capital that will facilitate the rapid transformation of production processes as well as the composition of the goods and services we produce.

There are five key priorities we must get right in order to raise the annual growth rate of potential GDP to well above the 1.8% trajectory pre-COVID. It will involve a combined effort of governments, businesses and households:

- Enhance digitization of production of goods and especially services.

- Extend the life of a cleaner resource sector and facilitate a higher value-added composition.

- Maximize participation and adaptation of labour force.

- Enhance effectiveness and efficiency of public services.

- And, of course, restore confidence in fiscal stability, which will form the third and final part of this paper.

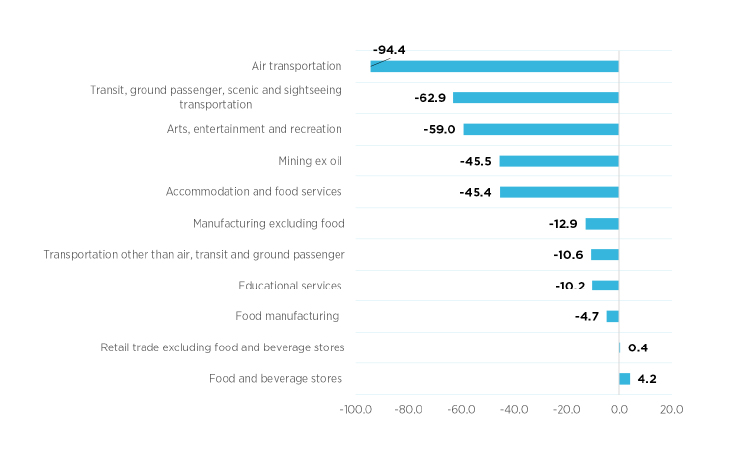

Productivity growth in Canada trailed far behind that in the United States (and several other OECD countries) through the first half of this century; it has nearly matched a weakened U.S. standard since the Great Financial Crisis. Having experienced the power of digital advances in almost every aspect of our economic and social lives, the COVID crisis reminds us of the absolute imperative to invest in becoming a digital leader. Although it is hard to measure just where Canada stands in terms of investment in digitally related technologies, we can see that Canada lags the U.S. in terms of spending on the critical component of software. Between 2010 and 2019, real business investment in software increased four times faster in the U.S. than Canada. (See Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5: Drop in Canadian Real GDP by June 2020 Relative to February (%) | Selected Industries

Source: Statistics Canada, table 36-10-0434-01.

Figure 6: Real Business Investment in Software | 2012 Chained $, B.

Sources: Statistics Canada, table 36-10-0108-01 and US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Just as great effort was expended well into the 1940s to ensure all Canadians had access to electricity, so it is necessary to do the same today with high-speed Internet. We must make the leap forward into a 5G world and ensure everyone gets the chance to come along for the ride. Canadian producers have been slow to seize the opportunities provided by the applications of such digital-enabled technologies as artificial intelligence and big data. We have been sluggish in the collection, generation and storage of data. Despite the leading role of AI research in Canada, our firms and institutions have been generally behind the Americans applying these new techniques.

Our telecom providers need to expand the quality and geographic range of high-speed broadband services. Companies, especially small businesses, need to catch up with those in other nations in providing online delivery of goods and services. Financial institutions also need to surge ahead on real-time services. The impact of COVID has demonstrated all too clearly how puny relative to potential has been our effort to deliver services virtually and how Canadian consumers and businesses have failed to insist on delivery of these services virtually and on time.

Finally, and very importantly, it is imperative to address the fact Canadian businesses have trailed far behind their U.S. counterparts in registering patents and generating revenue from the establishment of IP, especially in capturing the results of research efforts. By failing to invest in commanding their own IP (often for products and processes they have worked hard to develop), Canadian businesses have effectively been willing to forego significant streams of potential income from a new intangibles economy in which intellectual assets are surpassing physical ones as generators of wealth.

As a result, Canada ran a net current account deficit in the fees and royalties paid for the use of intellectual property of almost $9 billion a year between 2015 and 2018. In a post-COVID world, where Canada’s returns from the exploitation of our natural capital (physical resources) is likely to progressively diminish over time, it is imperative we concentrate in building the intellectual capital from which we can earn replacement income. Just as Canada has lagged behind other countries in commercializing our research efforts, now we have fallen behind in generating IP rents from our R&D expenditures.

Our experience in coping with COVID over the last six months has provided vivid illustration to Canadian households, businesses and governments of the great importance of improving our capability of providing and accessing online and virtual services; securing access to data and to the tools to use that data; creating and exploiting IP (especially medical IP); and investing in the expansion of broadband services. This experience has also illustrated to us all—employers, employees, students and the self-employed—the importance of upgrading our digital skills in order to muster the individual and collective capacity to produce and compete effectively in the 2020s.

The gains to be extracted by individuals, small businesses, public services and just about everyone else from a full-throated digital conversion are well illustrated by the fact Shopify, our most successful start-up since Research in Motion, surpassed the Royal Bank of Canada in market capitalization early in the pandemic. (And such services don’t cross physical borders in trucks or boxcars, like canola and aluminum, making them less subject to overt protectionism.) The digital economy is everywhere, and therefore the conditions need to be created to reap the rewards by intensifying the digitalization of all our industries—old and new, tech and not.

Canada has relied heavily on the export of natural resources—especially oil—to cover the cost of importing goods and services. From 2010 to 2015, oil and gas contributed disproportionately to lifting us out of the economic trough of the Great Financial Crisis; oilsands investment and added production allowed Canada to escape relatively unscathed and bounce back quickly. Even in 2019, oil alone generated net export earnings (after covering the costs of imported foreign oil for the eastern parts of the country) of $62 billion, our largest single category and enough to largely cover the net import costs of consumer goods and travel services. This will pose a major challenge given that global demand for oil is on a long-term downward trajectory and the price of crude is likely to remain well below 2010-2015 levels.

To generate continued export earnings, Canada’s energy industry will need to invest in equipment and technology that reduce both costs and carbon emissions, as well as ensuring we have sufficient capacity to transport product to multiple markets. Governments will need to pursue policies that facilitate such private investment (or at least not frustrate it).

If the sector fails to generate strong export earnings and to attract foreign direct investment, this will create downward pressure on the Canadian dollar, translating into higher prices for all other goods and services Canadians buy. The lifespan of oil needs to be stretched out—while adjusting for the negative effects of emissions—until we have developed replacements for the lost export revenues. Opponents of a strong oil and gas export sector fail to recognize that these earnings are needed to pay for the greening of our energy supplies. At the same time, it is essential in modernizing the oil and gas industry to find ways to monetize the investments made in devising improved technology—both by exporting our technical services and, very importantly, by creating the rights to the intellectual property we are creating here in Canada.

We must also move up the value chain. Canada can capture more of the economic value of oil and gas production through increased investment in technologically advanced transformation of hydrocarbons into petrochemicals, hydrogen, and other derivative products. The objective is to build on our current advantage of both natural and human resources to perpetuate and grow the value of global sales derived from these resources, transitioning away from emitting carbon while turning a fading industry into a renewed powerhouse. This is a sector that cannot be abandoned but must be transformed and must be given appropriate fiscal incentives to finance its clean conversion.

Innovative investment effort is also required to expand the value that can be derived from our other natural resources. Over the years, our mining sector has demonstrated its ability to generate revenues from the export of technical and developmental expertise even as volumes have declined. Geological and mining expertise as well as a well-developed marketplace for raising capital have generated service-based export earnings. Knowledge built on domestic production forms the backbone of this mining services economy. This is a strength that can continue to be augmented through the application of AI and new tools for data analysis. At the same, time, these new tools can be applied to the environmental assessment processes to increase efficiency and reduce the time lags involved. Mining provides a shining example of how Canadian skills developed in a low-tech industry can generate income and exports far greater than the simple export of the basic commodity.

Finally, global disruptions due to COVID have also amply demonstrated the value of a secure and reliable supply of food and the capital and labour inputs required to sustain that supply. The virus has revealed some of the shortcomings in the growing, processing, and distribution of food and food products as well as the skilled labour requirements of this industry. Climate change will require the application of innovative technology to maintain and enhance yields, to manage water and soil issues, and to develop improved products. And in agriculture, just as in oil and gas, increased emphasis needs to be placed on capturing the value of research efforts though product and process patents. We already have a successful track record: the government-industry development of canola was a great triumph of applied science, and the adoption of pulse crops has made Canada a world leading exporter

Agriculture is a high-tech business. Gains in productivity and value added will be secured when all players in the industry—including governments—view it this way and act accordingly. Government supports, services and regulators need to be focused on facilitating growth in the value of output and not just on stabilizing farm incomes, however important such stabilization might be.

This brings us back to a final overarching point about ways to enhance added value and productivity in all parts of the natural resource sector: the importance of clear, predictable, consistent and generally applicable regulation across regions and among orders of government. Resource development is generally both very capital intensive and subject to risk of wide fluctuations in commodity prices. To achieve the high levels of investment required in resource industries, investors must accept the natural risk of global price fluctuations. Calculating and embracing risk is what investors do. But what they find difficult is the added uncertainty posed by the conflicting interests of federal, provincial, First Nations and municipal governing authorities, which create regulations that are too often unpredictable, ambiguous and erratic—and then subject to lengthy processes and frequently hazy interpretation by courts. Canadian government and their regulatory emanations (especially environmental ones) have managed in this century to compound the natural risk of investing in capital projects to extract, process, and transport commodities (both renewable and non-renewable).

Tragically, this is happening at the very moment Indigenous businesses are increasing their ownership stakes in resource developments and exports. It is a terrible time in all ways to be driving away investment.

Nor has this unfavourable change in our brand come about because our regulations are tough—i.e. by design aimed at assuring the highest quality of production, and environmental protection and labour standards. Canada’s investor beware problem flows from the volatile regulatory and legal regimes with respect to environmental approvals, provincial obstacles to interprovincial trade and local zoning regulations. The negative impact of our uncertain regulatory process is a factor that is totally within our power to fix. The post-COVID economic pressures raise the penalty of failing to do so.

Achievement of a decent level of growth in Canadian per-capita incomes in the years ahead depends crucially on an increase in the number of hours worked relative to the size of our population—and even more importantly on the quality of output from each of those hours.

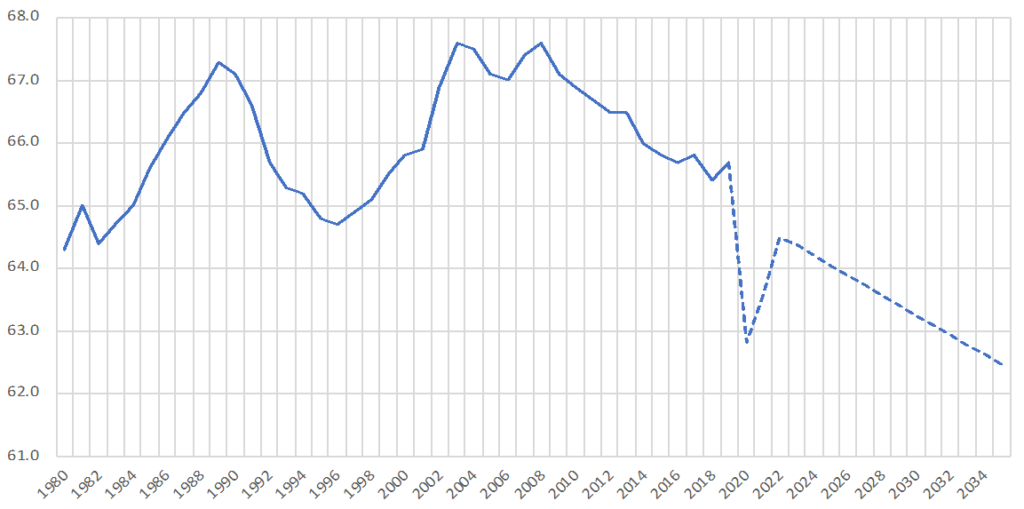

Like a steady drip, Canada’s labour force participation rate has been falling, virtually unnoticed, by 0.2% a year for the better part of a decade. The positive effects of immigration and improvements to participation by most age groups (but especially 60+ workers) has only partially offset the effects of an aging population. The inescapable objective of policy at such a time is to ensure not only that those who want to participate can find a job, but most importantly that they have access to the tools (equipment) to be fully productive and are provided the opportunity (education and training) to gain the knowledge and skills to produce the highest value of output. (For long-range projections of aggregate labour force participation rates and labour productivity growth, see Appendices B and C. For the latter, the projection is based on an assumed persistence of the recent trend of low growth.)

From the perspective of maintaining labour supply, raising the participation of two key groups stands out: older workers (those between ages 60 and 74) and workers with caring responsibilities (for children, the elderly, the disabled). They, therefore, should be the prime focus of policy.

For older workers, the key is to remove the disincentives contained in our OAS, CPP and tax system in the form of the very high effective rates of taxation on labour income, and to provide opportunities for transition to other types of employment, especially in caring occupations. For those with children, access to childcare is crucial. For those with other family caring responsibilities, additional leave has been demonstrated to be an essential element in fostering participation.

One of the simplest lessons from the COVID experience is how working from home, when virtual work is feasible, can in many instances increase productivity and reduce unproductive commuting time. While no one size will fit all, measures to facilitate virtual work, ie. choice, can effectively expand the supply of productive labour hours. Along with reforms to increase participation of older workers, migrants, and those with caregiving responsibilities, virtual work can help offset the natural decline in the growth of labour hours due to population aging.

Even more important than rebuilding the quantity of available labour is ensuring the skill mix of workers adjusts rapidly to meet the evolving requirements of a changing economy. This involves an increased focus in our education system to expand the base of STEM knowledge as well as the human skills that facilitate adaptation and learning throughout a working lifetime. It entails focus by employers and individual workers on continuing acquisition of new and upgraded skills. It requires reconstructing our employment insurance system to support and encourage skill acquisition during and before periods of unemployment. And, finally, it involves a focus on providing support for older workers to transition to less physically demanding occupations and to acquire the skills necessary to meet the increased demands for services for our aging population. By focusing on these critical areas, government policy can reduce unemployment though better matching of skills, improve the quality of labour hours supplied and help raise productivity. The payoff: more participation by a better prepared and more inclusive labour market will raise wages, reduce income inequalities and lead to a more globally competitive Canadian economy.

Naturally enough in an era of technological change, even with investment in these policies to improve the quantity, quality, and flexibility of labour, one can expect shocks in the job market will continue to occur, resulting in unforeseen periods of unemployment.

COVID has forcefully demonstrated that our current system of unemployment insurance is ill-adapted to provide temporary support to the growing proportion of workers who are self-employed or who do not enjoy a long-term continuing permanent relationship with a single employer. CERB was invented out of thin air to address this shortcoming, but is structurally ill-suited as a permanent feature to support workers during economic downturns. It recreates a version of the so-called welfare wall it took decades to dismantle.

A key challenge for the federal government in the post-COVID period is to rebuild the EI system to include self-employed and contingent workers who can then pay premiums and gain access to the benefit and training provisions of the system. We should retain the underlying philosophy of our flexible North American system, which recognizes that labour market churn involving periods of unemployment facilitates adaptation, growth, and improved productivity as opposed to European systems of layoff prevention (prohibition of dismissals combined with wage subsidies), which ultimately impose a serious adverse toll on hiring—especially by small and medium enterprises.

Finally, we need to enhance how government services maximize their contribution to stronger economic growth and better governance. Governments account for 25% of Canadian GDP (pre-COVID) and are directly responsible for the provision of many critical services (health, education, transport, justice and regulation). Provided in a cost-efficient way these will enhance the global competitiveness of the Canadian economy.

Historically, the public sector has been slower to adjust to technological change than the private sector. The pattern has persisted during the digital revolution. But the COVID crisis has forced change on public institutions, which have generally responded positively. Building on this momentum affords a major opportunity to institute more effective services and fairer access to them, and to save money.

Herewith is a summary of the services that could most benefit from an effort to bring them into the digital age.

- Health Care: Our experience during COVID has underlined the profoundly inadequate provincial systems of health record-keeping and management of data for service delivery, public health and research purposes. A major investment in improving health data, and exploiting that data through AI-based analysis, is the single best initiative to deliver both better care and reduced costs. By moving health care into the digital era and maximizing the virtual delivery of services to individuals, not only is the quality of care—especially primary care and preventive services—improved, but access to specialized care can be extended to all, including in rural and remote communities.

The proceeds from productivity improvements can be redeployed to address one of the ugly truths exposed by the pandemic—our inattention as a society to the care of the frail elderly. Through greater attention to digitalization, we can fix this gaping hole while keeping constant the health care share of GDP. - Education: No sector has been slower in adapting to the digital age than education. Adaptation requires investment of time and effort on the part of instructors in learning how best to deliver material and engage students virtually. It also requires system change to maximize the potential of online learning for children in school, for university students and for adults during their working lives.

- Justice: Our courts remain mired in 19th century procedure, which not only increases the costs of legal proceedings but often denies people (and businesses) access to justice. Increased use of virtual proceedings, digital records, and better data management can all contribute to improved justice and to improved enforcement by police and regulatory authorities.

- Regulation: There are two other key elements to enhancing the contribution of government services to economic growth: An improved and a consistent regulatory framework that allows business to invest with confidence and better public investment in infrastructure that facilitates the movement of goods, people and electrons within Canada and across our borders. Businesses can and should deal with market risk in making investments. But they can best deal with those risks if the legal and regulatory framework is clear, reasonably straightforward to comply with, and provides a high degree of certainty of continuity for the future. Unfortunately in Canada over the last few decades, federal, provincial and local regulation has become less clear, more complex, especially where jurisdictions overlap, and significantly more erratic and unpredictable. Not only has the cost of compliance risen over the last few decades for both small and big business alike, but erratic changes in the rules over the lifetime of planning an investment project have left investors increasingly reluctant to look at Canada as a good place to invest. Business can deal with clear rules to achieve social and economic goals—higher minimum wages or a carbon tax—but a platform of ever-shifting, detailed and often conflicting labour or environmental rules raise the risk of doing business in Canada without achieving the social and economic objectives those rules are ostensibly designed to promote. Rebuilding Canada after COVID requires that governments at all levels commit to rebuilding the “Canada Brand” through increased clarity and stability of the legal and regulatory process.

- Infrastructure: The 2015 promise of increased investment in infrastructure supported by the Canada Investment Bank has not been realized to date. In part because planning of major infrastructure is understandably difficult and requires a high degree of cooperation among different provincial and local government agencies, multiple private sector interests and federal agencies including the CIB. Post-COVID, we need to move forward with major projects to facilitate the movement of our goods across Canada and beyond our borders. We need to move people (and goods) efficiently in our urban areas, although the patterns of movement may now be somewhat different. Most importantly, we need to connect all households and businesses to high-speed Internet—especially those located outside major urban cores. Rebuilding infrastructure will require governments and private providers to tap capital markets for considerable financial support. This debt, even at currently low 30-year rates, will need to be serviced and, hence, projects will have to generate their own revenue either through direct user charges (tolls, farebox, utility bills) or dedicated taxes. Recognizing that some support from general taxation for expanded infrastructure is appropriate to recognize the “externalities” flowing from the expansion. However, without a commitment by governments to the principle that users should pay, the CIB will not be able to generate the private investment needed to bring Canada’s infrastructure up to the standard provided by the many countries that are able to attract private investment in their public infrastructure.

Governments moved swiftly in March to address the COVID-19 economic shock through unprecedented increases in direct spending, loans and temporary tax deferrals. Canada’s reaction began tentatively, but quickly grew to become among the largest fiscal responses among G7 economies.

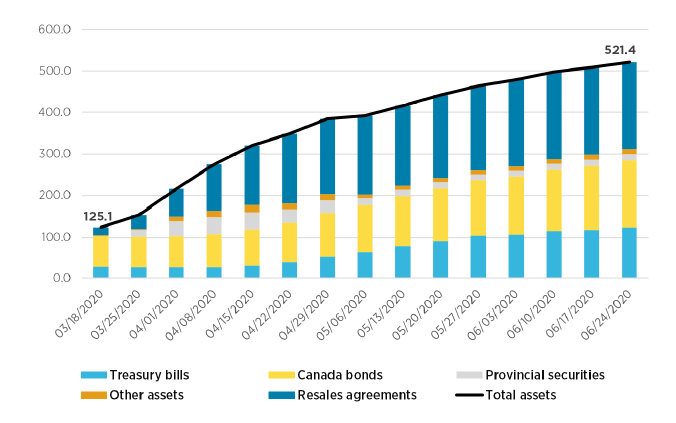

Globally, central banks moved equally decisively, providing liquidity support for business, and, even more importantly, massive asset purchases to push interest rates to historic lows. The Bank of Canada took extraordinary measures in pumping cash into the system to facilitate government and business borrowing, far in excess of what it did in 2008-2009. The bank’s balance sheet expanded from $125 billion in mid-March to $521 billion by the end of June, although the rate of expansion slowed over the summer (see Figure 7). With these dramatic actions, the bank has enabled governments to borrow exceptional amounts.

Figure 7: Evolution of Bank of Canada Assets Since March 18, 2020 (Billions of dollars)

Source: Bank of Canada.

All this has resulted in a sharp jump in the projected federal debt/GDP ratio from 31% to 49% in a single year. And further borrowing will inevitably be required in 2021-22 (and 2022-23) as the aftershocks of the crisis persist—at least until a vaccine can be introduced and distributed. The federal debt/GDP ratio could approach the modern peak level of the mid-1990s.

As for the provinces, generally their debt ratios rose sharply in 2009 and for the most part have never been brought back under control. Coming into the crisis, provincial debt/GDP numbers from Manitoba and everywhere east were higher than Ottawa’s (see Table 1). As a result of the crisis, provincial borrowing to pay for increased health and education spending and offset revenue declines will likely tally another $100 billion, of which the Bank of Canada can be expected to absorb more than $25 billion. Some provinces are sufficiently vulnerable that they may need a federal bailout. Together, the federal and provincial governments are on track to borrow close to $600 billion this year and reach a combined debt/GDP ratio of approximately 90%. This will put Canada slightly above the projected OECD average of 85%, but still below the G7 average of 105%.

Table 1: Net Debt to GDP Ratio: 2018-19

| % | |

| B.C | 14.4 |

| Alberta | 8 |

| Saskatchewan | 14.7 |

| Manitoba | 34.4 |

| Ontario | 39.5 |

| Quebec | 39.3 |

| New Brunswick | 37.8 |

| Nova Scotia | 33.8 |

| PEI | 30.4 |

| N&L | 46.3 |

| All Provinces | 30.1 |

| Federal | 34.7 |

Source: Department of Finance, Fiscal Reference Tables 2019 and Statistics Canada table 36-10-0104-01.

Even in the early stages of a recovery—and with a second wave lurking—a debate is breaking out as to whether we are accumulating public debt too fast. The answer is, simply, it depends. Some people take comfort in the rapid improvement of the debt to GDP ratio after the Second World War. But that was an era in which central authorities exercised extensive control over capital movements and interest rates, enabling them to impose so-called financial suppression—essentially conscripting household savings into the debt management effort at very low rates.

In the 1980s and 1990s, we experienced the consequences of high deficits and debt as confidence in Canada eroded. The dollar took a beating in the so-called Northern Peso crisis and interest rates kept rising—swelling debt servicing costs, and therefore the deficit, even further. This vicious circle was only tamed through drastic government spending cuts.

Today’s spike in the deficit and overall public debt is a fact of life not to argue over but to manage for better or worse. The key question: Will a continuing build-up of debt threaten the confidence in the government’s fiscal capacity and access to capital markets as it did in the 1990s, or are things materially different because interest rates are so much lower? The answer is likely that today’s circumstance is in fact different, and likely to remain so over the next couple of years. In the medium-to-long run, however, the underlying problems associated with high debt levels are likely to re-emerge, as per the 1990s.

It comes down to the vital G – R equation (Growth minus Interest Rates). Simply put, if growth goes up at a faster rate than interest rates, then we should be fine. If interest rates go up faster than growth, then we are in trouble. Herein lies the “it depends” answer to how much debt is, under the circumstances, too much.

Fundamentally, the impact of past borrowing shows up as the burden of interest costs borne by current taxpayers. If the interest rate that government must pay to roll over existing debt is well below long-term average, as it is at the moment, then the burden on current taxpayers is low and creditors will worry less about a government’s fiscal sustainability. Conversely, if interest rates are high and rising (as they were in the early 1990s), the load on taxpayers goes up, along with the anxieties of creditors. Growth is the other variable. If the growth of government revenues (G) is expected to be high relative to the interest (R) government must pay when it rolls over past borrowing, then the interest payments will over time constitute a declining proportion of the budget and therefore generate fewer constraints on a government’s capacity to introduce new program spending or reduce taxes.

In short, if G (growth) is greater than R (interest rates), the burden of servicing debt falls over time while when R is greater than G, the burden of past borrowing becomes increasingly intolerable for current taxpayers. So the answer to the question of whether the question of fiscal sustainability is different today than it was in the 1990s depends on the expected relationship between G and R not just this year and next, but much more importantly in the years ahead (see Table 2 for historical averages).

Table 2: Financial Market Statistics

| Nominal GDP growth | Average bond yield | Nominal | |

| G | R | G-R | |

|

% |

|||

| 1979-1986 | 10.2 | 11.9 | -1.8 |

| 1987-1997 | 5.1 | 8.4 | -3.3 |

| 1998-2007 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 1.0 |

| 2008-2019 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 1.3 |

Sources: Statistics Canada tables 36-10-0104-01 and 10-10-0122-01.

Let’s first deal with G. The rate of growth of government revenues depends on the rate of growth of GDP. It is uncertain how fast both global and Canadian real GDP will expand over the decade ahead. On the basis of experience so far this century, it is not unwarranted to project global real GDP growth of 3.5% per year annually over the decade. Against that global backdrop, and depending on the quality of Canadian economic policies, it is also not unreasonable to project Canadian growth of somewhere between 0.7% per year (the projected growth of labour hours with no productivity gain) and 2.2% per year (assuming the highest productivity gain of 1.5% that we have achieved in the recent past). On average over the decade ahead, 1.75% annual real growth constitutes a realistic projection for Canada, assuming good economic policy. Further assuming the Bank of Canada continues to be successful in keeping inflation to 2%, government revenues at roughly current tax rates could grow at 3-4% per year over the next decade.

Meanwhile, the interest rate, R, the Government of Canada must pay to roll over past debt will depend on central bank policies to achieve inflation targets. If global and domestic excess supply conditions were to continue, then it would not be unreasonable to think that the current historically low R (0.5% on a 10-year Canada bond) might persist. On the other hand, once the recovery is firmly established, it is realistic to anticipate that R might return to 2019 levels (2.3% on 10-year Canada bond) although not all the way back to its 2007 level (4.5%).

These wide ranges of projected levels of G and R reflect the radical uncertainty about the economic future of the post-COVID world. If worries about continued excess supply versus demand over the next decade turn out to be correct, then both real growth and inflation will be very low, meaning nominal growth below 3%. In this scenario, central banks, including the Bank of Canada, have indicated that monetary policy would remain accommodative and interest rates maintained at or near the current zero lower bound. In this miserable low growth world, G – R would be expected to be in the order of a relatively safe 1 to 3 over the decade.

If, however, growth returns to its previous track as COVID fears dissipate and global trade strengthens, then inflation will tend toward or above the 2% target. In this case, monetary policy would be far less accommodative and interest rates might approach 2007 levels. So in this more favourable growth world, R might be expected to be at or above G, as was the case in the fiscally challenging 1980s and 1990s. (See Appendix A).

Where does all this take us?

It seems reasonable to base a fiscal planning scenario on the assumption that, over the course of the 2020s, both growth and interest rates would resemble that of the last decade, restoring G-R to the vicinity of 1.3% per annum on average. With a federal debt/GDP ratio of approximately 50% in 2021, the ongoing costs of servicing the debt accumulated by the end of this fiscal year ($1.2 trillion) would eat up about 7% of ongoing federal revenues. This is only modestly higher than the recent low point in 2017.

But the story does not end there. Should the debt-to-GDP ratio in 2024 climb—as expected—close to the 1990s level of 60%+ (and assuming a growth bounceback and continuing low interest rates), the share of revenues dedicated to debt service would over time stabilize at 10 cents on every dollar the federal government collects. On the one hand, that’s more than what it was in 2017 (7%). On the other hand, this burden on future taxpayers is in line with international standards and far shy of the unmanageable 35% share of revenue that debt servicing reached in the mid-1990s.

That said, one has to build prudence into the fiscal planning because neither growth nor interest rates are knowable, especially looking out a decade. The situation I had to deal with as deputy minister of finance in the 1990s was one of good growth, stable inflation but unexpectedly high interest rates. This meant the burden of borrowing costs as a share of ever-growing government revenues kept rising, and therefore required program expenses to be seriously slashed and painfully high unemployment insurance premiums left intact.

Our grasp of what comes next was tenuous before COVID-19 and is now even more so. Growth (G) could be weaker and interest rates (R) higher, pushing the share of revenues required to service debt well above 10% and squeezing out better spending, as it did just 25 years ago. It cannot be overstated that control of debt service costs is essential to maintaining social and economic programs and keeping the tax burden on the middle class at reasonable levels.

And so I would recommend:

- The government taper its deficit spending and borrowing needs in deliberate steps over the next two to three years, with the objective of bringing deficits down to 1% of GDP ($20 billion).

- The government move from using debt-to-GDP as its sole fiscal anchor to adopting one based on debt servicing costs.

- The government therefore tie future borrowing, expenditure and revenue plans to the rock of sustainable debt service costs not to exceed 10% of annual government revenues.

Ultimately, at this stage in our fiscal path, a debt servicing/revenue formula based on prudent growth and interest rate assumptions provides a better anchor for fiscal sustainability than the debt/GDP ratio alone.

There is a stipulation on fiscal management, however, which brings us back to the paper’s opening section on the critical importance of the current account. For G to remain greater than R over the medium and long term, government borrowing must be primarily used to finance investments that will augment the growth of domestic production and the global competitiveness of Canadian industry.

When investors—foreign and domestic—see the tangible evidence of Canada’s commitment to future growth (even in a carbon-constrained world), both our fiscal and current account balances will be more readily judged sustainable. Any risk premium that borrowers might otherwise demand will be eliminated, reinforcing the strength of the Canadian dollar and a lower R.

But if government finances are overly directed to maintaining today’s consumption over tomorrow’s return on investment, then G will be diminished, the risk premium on R will rise and, disastrously, R will exceed G. The resulting higher debt charges will place an intolerable and unsustainable burden on future taxpayers and limit the capacity of future governments to support Canadians in times of weakness.

In summary, what we need this fall is an economic plan from the Government of Canada that does three things:

- Provides for borrowing to begin a downward track starting in 2021 and 2022

- Uses that borrowing to augment investment in human, physical and intellectual capital with a mind to improving our productive capacity and export potential and, therefore, growth.

- Reduces the deficit/GDP ratio to no more than 2% in next two years and 1% thereafter, with a fiscal anchor established that interest payments on the debt will not exceed 10% of federal budget revenues.

What is clear is we cannot continue to borrow from foreigners in order to maintain our standard of living. It was questionable before COVID-19 and is untenable after. A permanently rising current account deficit is not sustainable. Inevitably, at some unforeseen moment, it will bite us in the back.

In the final analysis, rising domestic incomes require increased value-added production at home that can also be exported abroad. Governments can only redistribute income that is actually produced by Canadians. What governments must do is establish the regulatory infrastructure and fiscal framework that facilitate this production. Providing for the security of Canadians in times of crisis, particularly for the most disadvantaged, is a given for all orders of Canadian governments. Creating the conditions to increase productive capacities to help workers and businesses recover and rebuild is the true value-add we need from our governments.

Appendix A

| Current A/C | Goods Balances | Service Balances | Net investment income | Current A/C | ||||||||||||

| Total | Total | Energy | Elec-tronic. | MV & parts | Con-sumer Gds | Other | Total | Travel | Trans-port | Other | Total | Direct | Portfo-lio | Other | ||

| 1997 | -1.3 | 2.8 | 1.8 | -1.8 | 0.8 | -1.5 | 3.5 | -0.8 | -0.4 | -0.3 | -0.1 | -3.2 | -0.4 | -2.7 | 0.0 | |

| 1998 | -1.3 | 2.5 | 1.7 | -2.0 | 1.0 | -1.5 | 3.3 | -0.5 | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.1 | -3.3 | -0.4 | -2.7 | 0.0 | |

| 1999 | 0.2 | 4.1 | 1.9 | -2.1 | 2.0 | -1.3 | 3.6 | -0.5 | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.1 | -3.4 | -0.8 | -2.4 | 0.0 | |

| 2000 | 2.6 | 6.0 | 3.2 | -1.8 | 1.7 | -1.1 | 4.0 | -0.4 | -0.2 | -0.2 | 0.1 | -3.1 | -0.8 | -2.1 | 0.0 | |

| 2001 | 2.2 | 6.1 | 3.2 | -1.7 | 1.7 | -1.1 | 4.0 | 0.4 | -0.1 | -0.3 | 0.0 | -3.5 | -1.4 | -2.0 | 0.0 | |

| 2002 | 1.7 | 4.7 | 2.7 | -1.6 | 1.2 | -1.1 | 3.5 | -0.3 | -0.1 | -0.3 | 0.0 | -2.7 | -0.7 | -1.9 | 0.0 | |

| 2003 | 1.2 | 4.4 | 3.2 | -1.4 | 0.7 | -1.1 | 3.1 | -0.5 | -0.3 | -0.4 | 0.1 | -2.6 | -0.8 | -1.7 | -0.1 | |

| 2004 | 2.3 | 4.9 | 3.2 | -1.5 | 0.7 | -1.1 | 3.6 | -0.4 | -0.2 | -0.3 | 0.1 | -2.0 | -0.5 | -1.4 | -0.1 | |

| 2005 | 1.9 | 4.3 | 3.7 | -1.4 | 0.4 | -1.3 | 2.9 | -0.4 | -0.3 | -0.4 | 0.3 | -1.8 | -0.6 | -1.2 | -0.2 | |

| 2006 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 3.3 | -1.4 | 0.0 | -1.7 | 3.0 | -0.5 | -0.4 | -0.4 | 0.4 | -1.1 | 0.0 | -0.8 | -0.2 | |

| 2007 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 3.4 | -1.4 | -0.4 | -1.9 | 3.2 | -0.8 | -0.6 | -0.5 | 0.3 | -1.1 | -0.1 | -0.6 | -0.2 | |

| 2008 | 0.1 | 2.7 | 4.1 | -1.5 | -0.8 | -2.1 | 3.0 | -0.9 | -0.7 | -0.6 | 0.4 | -1.4 | -0.5 | -0.7 | -0.2 | |

| 2009 | -2.9 | -0.4 | 2.8 | -1.6 | -0.9 | -2.4 | 1.8 | -1.0 | -0.8 | -0.5 | 0.3 | -1.1 | -0.1 | -0.9 | -0.3 | |

| 2010 | -3.6 | -0.5 | 2.8 | -1.9 | -0.9 | -2.3 | 1.6 | -1.3 | -0.9 | -0.6 | 0.1 | -1.3 | -0.2 | -1.2 | -0.3 | |

| 2011 | -2.7 | 0.1 | 3.3 | -1.9 | -0.9 | -2.2 | 1.8 | -1.2 | -0.9 | -0.6 | 0.3 | -1.3 | -0.1 | -1.2 | -0.3 | |

| 2012 | -3.5 | -0.7 | 3.1 | -1.9 | -0.8 | -2.3 | 1.2 | -1.2 | -0.9 | -0.5 | 0.3 | -1.3 | -0.2 | -1.1 | -0.3 | |

| 2013 | -3.1 | -0.4 | 3.7 | -1.9 | -0.9 | -2.3 | 1.1 | -1.2 | -0.9 | -0.5 | 0.2 | -1.3 | -0.2 | -1.1 | -0.3 | |

| 2014 | -2.3 | 0.3 | 4.3 | -1.8 | -0.9 | -2.3 | 1.0 | -1.2 | -0.9 | -0.5 | 0.2 | -1.1 | 0.0 | -1.0 | -0.3 | |

| 2015 | -3.5 | -1.2 | 2.7 | -1.9 | -0.6 | -2.4 | 1.1 | -1.3 | -0.9 | -0.5 | 0.1 | -0.7 | 0.5 | -1.1 | -0.3 | |

| 2016 | -3.1 | -1.2 | 2.3 | -1.8 | -0.5 | -2.3 | 1.1 | -1.1 | -0.7 | -0.5 | 0.1 | -0.5 | 0.6 | -1.0 | -0.2 | |

| 2017 | -2.8 | -1.1 | 3.0 | -1.8 | -0.9 | -2.5 | 1.2 | -1.1 | -0.6 | -0.5 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 1.0 | -1.1 | -0.4 | |

| 2018 | -2.5 | -1.0 | 3.3 | -1.9 | -1.1 | -2.5 | 1.1 | -1.0 | -0.5 | -0.6 | 0.1 | -0.2 | 1.1 | -1.2 | -0.3 | |

| 2019 | -2.0 | -0.8 | 3.3 | -1.8 | -1.0 | -2.4 | 1.0 | -0.9 | -0.5 | -0.6 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 1.2 | -1.2 | -0.3 | |

Source: Statistics Canada, tables 36-10-0018-01 and 36-10-0019-01.

Appendix B

Canada: Labour Force Participation Rate: 1980 to 2035 (%)

Source: Statistics Canada, table 14-10-0327-01 and projection.

Appendix C

Canada: Labour Productivity Growth – Total Economy (%)

Source: Statistics Canada, table 36-10-0480-01.

PARTNERS

Private Sector Partners: Manulife & Shopify

Consulting Partner: Deloitte

Federal Government Partner: Government of Canada

Provincial Government Partners:

British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario & Quebec

Research Partners: National Research Council Canada & Future Skills Centre

Foundation Partners: Metcalf Foundation

PPF would like to acknowledge that the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the project’s partners.