Improving Public Services: A Strategic Approach to Digital Infrastructure

Tackling the deficit and addressing Canada’s productivity lag by Neil DesaiIn the years leading up to the COVID-19 global pandemic, the Government of Canada made a policy decision to stimulate the Canadian economy by committing $160 billion in infrastructure spending between 2016 and 2028.

The economic argument for the stimulus was that it would bolster Canada’s lagging economic growth. The most common argument for more public expenditure on infrastructure is to get tangible goods, such as natural resources and manufactured goods, to market. However, such tangible assets have been economically leapfrogged by intangible, digital assets, such as software and other forms of intellectual property.

Despite the fact that the federal government alone spends $8 billion on its technology annually and billions more in economic-development activity, Canada is not well positioned for a global economy driven by intangible assets. The country’s ability to innovate to the benefit of its economy has been on a steady decline for the past 20 years — and, at the same time, the global marketplace has gone through a digital transformation. Consequently, Canada’s vast public expenditure on social programming is under pressure.

The shortcomings of our system have been put into sharp focus by the COVID-19 crisis. As a result of the pandemic, the federal deficit is expected to rise to $343-billion, and debt will exceed $1.2 trillion in 2020. Canada’s precarious economic position calls for innovative policies that will enable a greater contribution from the technology sector as we recover from the pandemic. The post-COVID world presents an opportunity to increase the stimulus multiplier on Canada’s current infrastructure funding envelope and reduce the government’s long-term fiscal exposure through policy innovation.

By expanding the traditional definition of infrastructure to include digital infrastructure, applying a strategic lens to the selection of projects, developing the policy foundations to enable it and directing a portion of the stimulus funding and annual base funds for technology to it, the federal government can begin to address multiple structural challenges. Specifically, government can build the digital infrastructure its public sector requires, which would also lay the foundation of an ecosystem that increases its innovation outputs, including exports, while improving public services, and creating tangible efficiencies and subsequent fiscal savings.

All levels of government in Canada have long subscribed to a narrow definition of economic infrastructure. They have largely focused on traditional infrastructure, such as roads, bridges and ports. These investments paid strong dividends in the last generation of Canada’s economy by reducing the cost of getting tangible goods to market. The investments were supplemented with social infrastructure projects, such as the building and upgrading of hospitals, schools and community centres, which focused on maintaining the population’s quality of life.

However, the experience of COVID-19 and the related economic shutdown exposed that governments and the organizations they fund have not invested enough in digital infrastructure to support and sustain essential services—such as health care, education and the justice system—in times of emergency. Courts have nearly ground to a halt. Non-COVID-related health matters and non-essential surgeries were paused. And public schools continue to scramble to provide some semblance of a curriculum online.

The government of Canada was unable to leverage its employment insurance (EI) software infrastructure to deliver the Canada Emergency Response Benefit in a timely fashion. The EI software was written in a generations-old coding language and wasn’t sufficiently scalable to service the vast number of Canadians out of work as a result of the pandemic.

In its current infrastructure plan, the federal government has emphasized “green infrastructure.” To meet the needs of increasing urbanization, and to honour national commitments for reduced greenhouse-gas emissions, investment in green infrastructure has largely come in the form of financing municipal mass transit in Canada’s largest cities. Consecutive governments have also broadened their definition of infrastructure to include expanding broadband internet access to rural communities.

The intention with these investments is mainly to contribute to Canadians’ quality of life. While this is a worthy goal, the investments deliver a low economic multiplier. This means they do not meaningfully contribute to sustainable economic growth, which is the long-term purpose of stimulus funding.

Digital infrastructure can be a foundation of the important work of government. The government’s reliance during the pandemic on tele-health and distance education demonstrate the ability for digital platforms to enable essential services. Although, simply moving existing services online will not achieve the public sector’s broader objectives.

At all levels of government, digital infrastructure policy must start with a clear focus on prioritized objectives. An obvious starting point is to improve the public services that could be delivered digitally to Canadians.

Another focal point should be projects that have a clear mandate to deliver quantifiable efficiencies in the form of downstream fiscal savings. The broader public sector at the federal, provincial and municipal levels is ripe for a thoughtful review of how technology could streamline organizational workflows—empowering personnel to focus their attention where they can make the most valuable interventions in the delivery of services—while leveraging technology to focus on mundane, repeatable tasks with speed and precision.

The opportunity to achieve downstream savings from digital infrastructure procurement will not happen organically. There has to be a policy prescription in the procurement and development processes of digital infrastructure.

For example, outfitting the thousands of Canada Revenue Agency frontline workers administering EI with new software on an updated code-base may make them incrementally more efficient. But to achieve meaningful fiscal savings, the government must re-imagine how the service can be delivered with less human intervention. Such operational expenditure savings can be achieved humanely through natural attrition.

A purpose-driven, risk-managed “co-development” approach to procurement

Using technology to improve public service delivery and provide fiscal savings is simple conceptually. In practice, the government of Canada has a poor track-record procuring technology, specifically software, to modernize its services and interactions with Canadians. The Phoenix pay system and the revitalization of the government of Canada’s websites are two recent examples of the pitfalls government has faced replacing mainstream technologies.

The procurement of technology by government at all levels in Canada has resembled that of traditional infrastructure. Requests for proposals (RFPs) outline all capabilities required, as defined by the end user, and evaluation is conducted by independent procurement officials who are largely focused on identifying the lowest bids. Without a strong understanding of what the market has to offer, government may first issue a non-binding request for information (RFI) from the vendor community that informs the development of an RFP. Even relatively small technology procurements can take months or even years to complete through this approach. In the meantime, technologies often evolve, and the RFPs are out of date the moment they are posted.

This inefficient approach has empowered large, multinational technology companies with the personnel and balance sheets to engage in processes with long horizons. Such companies often use the tactic of submitting a purposely low bid. Should they win, their first move is to leverage their existing software assets, which have virtually no cost of goods sold for software products from their existing portfolio. Then they supplement these assets with patchwork solutions to meet the minimum requirements of the RFP.

In turn, costs often spiral well beyond the budget, products are delivered late and are missing significant capabilities — or some combination of these issues. Smaller, more nimble, early-stage companies are moving too quickly to invest in purposely cumbersome processes that deliver sub-optimal technology solutions.

This is not to say that some of the public sector’s digital infrastructure needs cannot be achieved through off-the-shelf-technology procurement. Existing technologies should always be carefully evaluated before ruling them out. However, when governments procure technologies aimed at creating organizational efficiencies, they should always engage in a highly iterative process, bringing together the developer and end user. A minimal viable product should be defined early in the procurement, and all off-the-shelf or configurable options should be ruled out before considering custom development.

If a straightforward solution does not exist, flexibility in the traditional procurement process is required. All potential bidders should have access to end users of a proposed solution. The winning bidder must continue to have access to users through an agile development process so they can learn and iterate as required. This approach is often referred to as “co-development.” It has a higher likelihood of success, as both risk and responsibility over the outcomes are shared between the developer, procurer and end-user.

The evolution of procurement must also incentivize vendors to build and deliver towards the minimal viable product incrementally. Under traditional procurement approaches, vendors, especially those that strategically underbid, are actually given incentive to fail in delivering the requirements on time. This is due to the reality that government buyers are known to amend or expand contracts with the hope of getting projects on track. Many such technology procurements now have built-in delivery time extensions and cost increases.

The co-development approach is a departure from the traditional methods by which government does procurement. However, with new technologies, there is a need for two-way validation. The first piece of that validation is to define, with a high degree of specificity, what success looks like. This must be followed by an evaluation of whether the bidding party has the capability to deliver a working prototype in a timely and cost-effective manner.

This approach falls between traditional RFPs and RFIs. The traditional approaches, which create walls between end-users and suppliers, were largely set up to maintain transparency and accountability. These are important features of public procurement in Canada and should be woven into the procurement of digital infrastructure. But they cannot supersede the intended outcome as an objective of the process. Interactions between end-users and developers that allow for common understanding and interaction can embody transparency and accountability if government is willing to innovate in its procurement processes.

Delivering public sector efficiency through digital infrastructure is important in ensuring Canadians are well served. However, it alone will not increase the economic multiplier on Canada’s overall infrastructure stimulus. If the federal government wants to drive long-term economic growth through its investments in its own digital infrastructure, it will have to take concerted measures in its policy design.

The Build-in-Canada Innovation Program (BCIP) is a supply-side technology procurement program that has operated for more than a decade. It provides modest funding to support Canadian technology providers and allows federal departments and agencies to test their prototypes. The government is under no obligation to procure the final product. The program has delivered little in the way of substantial government efficiencies or economic growth.

In 2017, the federal government created a demand-driven domestic technology procurement program called Innovation Solutions Canada. The program was modelled after the United States’ federal government’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program. The SBIR program enables government agencies to identify their top challenges they believe technological solutions could solve. American small-and medium-sized enterprises (SME) can bid on solving these challenges using a co-development approach. Similar programs exist in Japan, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

The government of Canada consolidated the management of Innovation Solutions Canada and the BCIP and renamed the latter “The Testing Stream”. However, they continue to separate their technology investments in their own digital infrastructure, developed by Canadian providers, into two siloed policy objectives:

- Creating economic growth through Canadian technology providers; and

- Delivering efficiencies in their own operations through technology innovation.

The technology sector in the United States is large, diverse and includes a robust SME contingent focused on public-sector technologies. Therefore, SBIR challenges garner significant interest from their government clients and technology vendors. Both benefit from the outcomes, which include the initial development investment being de-risked, and that the firm and macro-level economic outputs are driven through the subsequent export of the technologies developed.

Canada, in contrast, has a nascent technology industry. Companies that specialize in public sector-related technologies also reduce the viable pool of those that could deliver government program and service efficiency and create economic growth as a result of their developments through a purely demand-driven program.

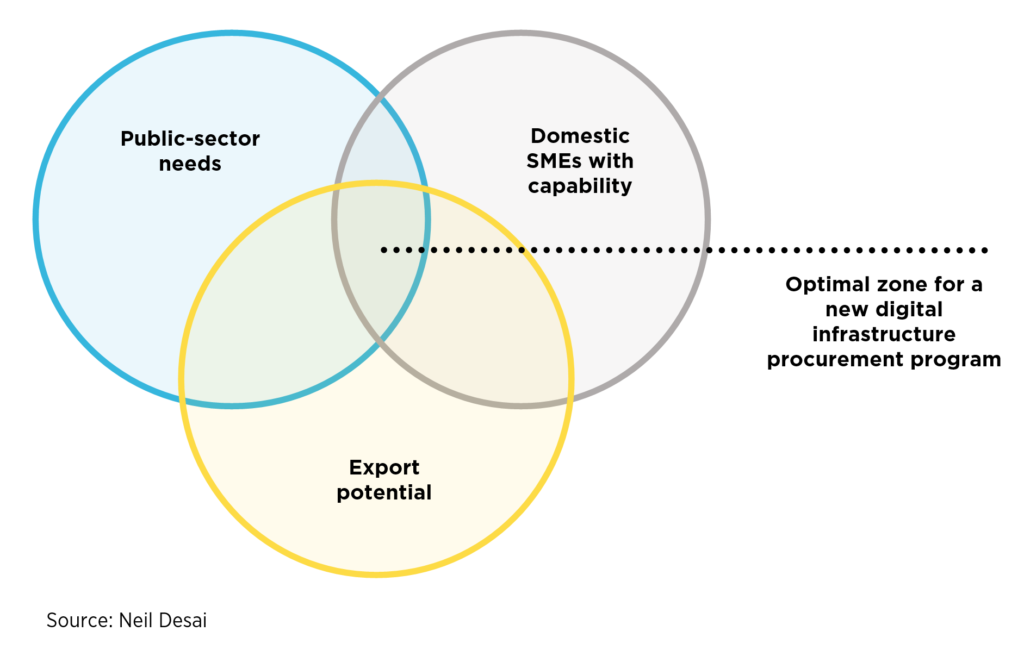

If the government of Canada wants to achieve efficiencies in the delivery of public services and, at the same time, use procurement to drive economic growth through the development of intangible assets, it will have to take a strategic approach to its digital infrastructure investments.

Governments will have to identify the greatest opportunities to drive efficiencies through technology in the public sector. At the same time, they will have to identify emerging domestic technology companies that have the ability to drive tangible efficiencies in these technology areas. They will then have to shape procurement around the unique capabilities on offer by Canadian companies that own proprietary technologies, or have the ability to develop, protect and commercialize them globally.

This approach would alleviate the risk of bilateral or multilateral trade disputes. Many of Canada’s recent international trade agreements open domestic public procurement, at all levels of government, to international bidding. By focusing strategic digital infrastructure investments in areas where Canadian firms can deliver on specific requirements with proprietary technologies or abilities, the federal government would remain in compliance with its trade obligations. Foreign firms would not be explicitly ruled out of the procurement process, but they would be at a strategic disadvantage.

A final, concurrent policy objective will be to evaluate the export potential of such technologies as domestic procurement alone cannot drive a strong economic multiplier. Therefore, technologies will have to be purpose-built for the Canadian market and other global customer requirements and standards. The government of Canada could serve as the reference customer and the standard setter for new technologies that drive efficiencies for global customers.

Efficiencies and an economic windfall from a strategic digital infrastructure procurement program can only be realized if government closely examines the broader enabling policy foundations to commercializing digital technologies. With traditional infrastructure, the important foundational policies reconcile capability needs with systemic considerations. For example, government procures roads and bridges based on the needs of society and the economy within the confines of existing products and safety standards. It must take a similar policy approach to the development of digital infrastructure.

Fundamental to the development of modern digital technologies that create organizational efficiencies, such as automation and artificial intelligence applications is their enabling data. In the realm of public services, this can include sensitive data that pertains to healthcare, education, policing, employment and finances. Governments across Canada will have to create a data strategy that reconciles multiple policy objectives, such as the privacy rights of Canadians, data sovereignty and the efficient use of aggregated and obfuscated personally identified data for public goods.

The government will also have to ensure either it is selecting technologies to which Canadian firms own the intellectual property, or that Canadian firms have the ability to secure and maximize the economic benefits of a strategic digital infrastructure program globally. For Canadians to reap the benefits of the technologies they invest in, it is vital to develop an intellectual property strategy that spans all publicly financed early-stage research and development activities in companies and research institutions through to commercialization.

Global adoption of technologies co-developed between governments and domestic companies will not necessarily grow organically. The global technology market continues to expand rapidly, including highly contested verticals with large public sector buyers, such as health-tech, smart cities and cybersecurity.

After having had their products procured by Canadian governments, Canadian companies should feel confident that they can market abroad. Advocacy done on behalf of Canadian companies by organizations such as the Trade Commissioner Service could also help technologies be adopted by foreign governments. A further, strategic move would be for Canadian companies and the government to standardize the co-developed technology through global bodies, such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). By developing standards aligned to proprietary technologies, Canadian firms can solidify existing procurements and grow out their sales opportunities in adjacent markets.

The COVID-19 crisis has reminded us that digital services, and the infrastructure through which they are enabled, are not only critical to Canadians’ quality of life, but could also be driving the competitiveness of the Canadian economy. To make this happen, governments must evolve their role from being simple issuers of RFPs to becoming strategic co-designers of processes, systems and solutions that improve services and reduce costs through the development of IP, and accumulation and application of data. They too have a role in bringing such co-developed technologies to global markets.

As the government of Canada shifts its policy focus from addressing the health impacts of COVID-19 to responding to the immediate and long-term economic implications of the pandemic, infrastructure undoubtedly will form a key plank of its economic stimulus policy.

Updating social and transportation infrastructure will be useful for improving quality of life for Canadians. But the self-perpetuating advantage lies in using economic stimulus to jolt investment and employment through the development, execution and export of digital tools and services. Such intangible assets are to the 21st century what resources were to the 19th and 20th centuries.

The federal government has a post COVID-19 opportunity to make strategic investments in technologies that achieve its policy objectives through the co-development with Canadian SMEs of technologies that can be exported to global markets. The federal government spends $5 billion annually on information technologies (IT) and another $3 billion on applications, devices and IT program management. Between these resources and the infrastructure budget, there is an opportunity to identify sources of funds to meaningfully invest in technologies that will drive better services and create internal efficiencies while helping Canadian SMEs scale globally.

Like any investment with a higher potential for return, a strategic digital infrastructure program involves risk. In developing such a program, the government must take a portfolio approach to account for this higher risk and instill patience in the evaluation process. The goal should not be to have every project deliver incremental savings and economic growth through exports. It should be to have a reasonable number of projects that deliver exponential savings and subsequent export activity. This risk profile will inevitably mean some projects fail, for which public opinion will have to be sensitized.

Succeeding on the multiple objectives of a strategic digital infrastructure program requires an approach that bucks conventional Canadian public policy as it relates to procurement, risk and collaboration with Canadian companies. By pursuing such a program, Canada would put itself on a stronger footing and begin removing some of the structural barriers that inhibit Canada’s technology sector from competing in global markets. It would also pay dividends by growing Canadian-operated technology companies that employ thousands with quality jobs and drive sustainable economic growth to the benefit of all Canadians.

Partners

Private Sector Partners: Manulife & Shopify

Consulting Partner: Deloitte

Federal Government Partner: Government of Canada

Provincial Government Partners: British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario & Quebec

Research Partners: National Research Council Canada & Future Skills Centre

Foundation Partners: Metcalf Foundation

PPF would like to acknowledge that the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the project’s partners.