The Online News Act gets an edit. What it means for the Canadian news media.

In a terse news release issued last Friday, Metroland, once Torstar’s revenue juggernaut, announced it was filing for bankruptcy protection. And just like that, 605 people lost their jobs, 4.2 million people in 70 towns lost the print editions of their community newspapers, a yet-to-be determined number of these papers’ digital sites will also close, and the future of Canadian news journalism—already bleak—became that much darker. The company claimed it didn’t even have enough money to pay severance.

The reason? Advertising. And the lack of it. The community papers were a vehicle for the delivery of advertising flyers, which paid for the journalism that informed those communities. But as with newspaper classified and display ads, flyer advertising has atrophied in the face of digital technologies.

The Metroland closures are exactly the sort of thing supporters hoped the government’s contentious Online News Act would prevent. It is a hope too far. The Act is not yet in effect, and in any case the government remains mired in a dispute with the tech giants, which have captured the advertising that once fuelled the news industry.

The Online News Act rests on the premise that news is a public good accessed and shared via digital portals, most prominently Google and Facebook, and that news companies should be compensated for use of this content. The tech companies counter that the news media seek and benefit from exposure via their platforms, and so mandatory compensation is not justified.

Facebook, which has been backing away from news globally, has refused to negotiate and has moved instead to simply disallow the circulation of Canadian news items on its platform. Google, although it has threatened similar action, has not broken off discussion. The federal Department of Canadian Heritage remains in discussions with Google Canada, while Google HQ, which has a strong interest in precedents it does and does not want established for the rest of its empire, hovers on the sidelines.

After considerable summer unrest over the Act, the government, with little ado, released a series of regulatory measures two weeks ago that make for an appreciably different Online News Act. They have subtly but significantly transformed it into a hybrid of the two approaches the government originally considered before writing the legislation.

The approach the government adopted, on the urging of the news industry, was inspired by the example of Australia, which viewed the problem of an ever-diminishing news sector through the lens of anti-competitive commercial behaviour. Australia passed legislation that would compel the digital duopoly to negotiate fair compensation with the news media, or subject it to binding arbitration.

The alternative considered would have been to simply impose a levy on the tech companies, with the resulting funds then distributed to the news media, presumably by some non-governmental granting agency, a news industry equivalent of the Canada Media Fund. Google executives argued for just such an approach in an appearance before a Parliamentary committee in April.

The regulations now attached to the Act introduce two important aspects to the law. First, they spell out the conditions under which Google can be granted an exemption from the legislation. As in Australia, the Act allowed Google to skirt compulsory bargaining and possible arbitration by initiating negotiations itself. The regulations set out a detailed set of specifications for these “voluntary” negotiations. Second, the regulations introduced a formula that places a ceiling on how much a platform would be expected to pay the Canadian news media.

One might quibble that something done voluntarily that otherwise would be mandatory is hardly voluntary. But it’s possible the measures have been designed to address core concerns on the part of Google. They would allow the company to accede to the spirit of the law without being technically forced to do so. Rather than being subject to the authority of the Canadian state, Google could simply agree to a set of expectations as set out in the regulations. And these expectations shift the burden of organizing the negotiation process from the platform to the news media, which must group themselves into bargaining collectives.

As well, instead of being faced with an indeterminate liability, the regulations put a ceiling on Google’s support for the news media based on a formula that starts with its global search revenue, multiplies that by 2 percent (Canada’s share of the entire global economy), and then takes 4 percent of that to yield a figure of $172 million.

The regulations therefore combine the fair bargaining aspect of the Australian model with a flat levy on the tech giant, thus a hybrid. In another interesting twist, they do so without the need for a granting agency like the Canada Media Fund to allocate the money. Rather, this would be done through the negotiations with news media bargaining collectives.

Ever since the publication in January 2017 of The Shattered Mirror: News, Democracy and Trust In the Digital Age, The Public Policy Forum has been at the forefront of understanding policy options and trade-offs in the news sector and has played midwife to such measures as the Local Journalism Initiative (a program that funds reporting positions in otherwise under-covered areas), the elimination of a consumption tax advantage that, perversely, fell on foreign-owned digital companies, the eligibility of journalism for charitable deductions, and the Canadian Journalism Labour Tax Credit, which provides tax credits of 25 percent for the first $55,000 of newsroom salaries.

Our purpose here is to probe and explain what the Online News Act now looks like, and what this bodes for the Canadian news media and for the Canadian information environment.

Fielding questions from PPF Media Editorial Director Colin Campbell are two of the principal authors of The Shattered Mirror and The Shattered Mirror: 5 Years On: Public Policy Forum President and CEO Edward Greenspon, and the former director of the School of Journalism and Communication and the Arthur Kroeger College of Public Affairs at Carleton University, Christopher Dornan.

Q: Last week we saw Torstar’s Metroland chain of 70 community newspapers file for bankruptcy protection. Will the Online News Act, assuming the tech giants agree to compensate the news media as the Act intends, prevent that kind of devastation to the Canadian news industry?

Ed: I don’t think any government program can ultimately save the news media unless the public was willing to allow news to become a permanent ward of the state. Judging from polls and focus groups, that seems unlikely to fly, in large measure because people can’t reconcile that to their genuine belief in journalism’s job of holding the powerful to account.

At the end of the day, we need some innovator(s) to come along with a better mousetrap idea of how to build winning business models around news. What policy should be doing is buying time so that news outlets —new and old, large and small—can keep newsrooms functioning through a transition. In so doing, it is critical that policy doesn’t lock in the legacy system and lock out the innovators.

Q: But why is the government intervening to help the news media? Isn’t the press meant to be independent from government—even adversarial?

Chris: Yes, it’s absolutely essential in a free society that the government have no jurisdiction whatsoever over what the news media report or the content of news commentary. And there are many prominent journalists in this country who oppose any government attempt to support their own industry on the grounds that the state has no place in the newsrooms of the nation. But this government is convinced that the threat to the very existence of the responsible news media is so severe that remedial measures are necessary and justified, while taking every precaution to preserve the independence of the news media.

And in fact there’s a long history of government support for the news media in Canada, starting even before Confederation when government postal subsidies permitted newspapers to circulate cheaply. The idea was that the country benefited if citizens had access to shared sources of information such as newspapers. Canadian Press, the wire service, began in 1917 through an Act of Parliament and a government grant. The government of the day believed it was in the national interest for the country’s newspapers to circulate information about what was going on in each of their cities and towns across this vast land. It was a nation-building initiative.

More recently, in the face of acute threats to the survival of news outlets, the government has introduced a number of policy measures to support news journalism, including a Journalism Labour Tax Credit (in effect, a subsidy for newsroom salaries), a digital news and subscription tax credit (an incentive for people to subscribe to online news sources), and the Local Journalism Initiative, a $10 million fund to pay for the salaries of journalists in underserved areas, primarily rural communities.

I don’t believe the government rushed to the aid of the news industry simply because it was failing as an industry. It’s unfortunate when an industry goes under and livelihoods disappear, but that alone doesn’t justify government intervention. No one felt compelled to rush to the aid of Blockbuster when video streaming made renting video cassettes obsolete. But the news business isn’t just any industry. As Senator Keith Davey put it in The Uncertain Mirror, the first volume of the 1970 report of the Special Senate Committee on Mass Media, “What happens to the catsup or roofing tile or widget industry affects us as consumers. What happens to the publishing business affects us as citizens.”

The Online News Act, and the other measures the government has taken to support news journalism, arise from a genuine fear about what might happen to Canadian communities if they no longer have reliable sources of information about themselves. How could a sense of community endure if people were ignorant about where they live and estranged from their own municipal affairs? It was about defending the social fabric, not bailing out companies being milked by foreign hedge funds who may well have been the authors of their own misfortune.

Ed: We argue in The Shattered Mirror that a bankrupt press cannot fulfill the functions of a free press. Reasonable people can disagree about whether we should view a free press as an absolute principle like the U.S. First Amendment or more in keeping with Section 1 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which allows rights to be limited “so long as those limits can be shown to be reasonable in a free and democratic society.” At the very least, programs must be designed to ensure any touch by the government is as light and as brief as possible. That means transparent formulas, arm’s length governance and no ongoing discretion over policies or money.

Q: The Online News Act follows the so-called Australian model. Will that model work here? Or perhaps I should ask first, has it worked in Australia?

Chris: If the goal was to channel revenue from the tech companies in order to keep the news media afloat, then yes, it has worked in Australia. So far, so good. But to what extent the Australian legislation has worked to improve public service journalism is another question.

There are two major criticisms of the Australian example. First, that it’s led to deals between the tech giants and the news companies that are utterly opaque—we have no idea how much any news outlet is receiving, and nor do the different news outlets know how much the others are receiving.

And second, that these deals favour the big news companies and entrench the status quo—revenues flow to moribund newspaper chains and broadcasters rather than to innovators, independent titles or outlets serving diverse communities. The complaint is that it’s keeping on life support a news ecosystem that deserves shock therapy.

Ed: Canada as second mover has learned from Australia and so there are important differences between its News Media Bargaining Code and our Online News Act. There, the minister exercises a lot of discretion, for instance to exempt from arbitration a platform that does its own deals with news companies. Here, that determination will rest with the CRTC instead. Handing responsibility for oversight of the Act to a regulatory agency rather than the minister’s office provides a measure of distance from the political realm, although for many it’s not enough.

As well, the Canadian model introduces various guidelines that would make it difficult for an exempted platform to discriminate against smaller operators, for instance, or to punish organizations it doesn’t like.

Q: But the threat of mandatory bargaining only works if there’s something to bargain over. Facebook has already shut off links to Canadian news organizations. What if Google does the same? If there’s no news available via the tech platforms, then there’s no one for the news media to negotiate with.

Ed: I guess we will know soon enough if Ottawa has a dance partner or whether the government and various news associations miscalculated. For now, let’s look at the two platform giants separately.

Facebook has never been a reliable news industry partner. At times, it has embraced news. At other times, it has rewritten its algorithm with zero notice and decimated the traffic of its so-called news partners. The Online News Act comes at a time when Facebook appears to be distancing itself from news in a number of countries. There’s even noise about it not renewing the deals it has struck in Australia.

On the one hand, it is Facebook’s right to be the author of its own business strategy. On the other hand, a different policy design, like the one recommended in The Shattered Mirror, which essentially would have based a levy on digital ad sales, would have collected funds from Facebook regardless of whether it distributes news. That said, it would have been difficult for policymakers to have adopted our preferred approach when most of the news companies were pushing for the Australia model. If both Facebook and Google walk, the industry associations will have to look themselves in the mirror, too.

We need to think in short and long term and relatively about who is really hurt if Facebook doesn’t carry news. Start-ups for sure. They require increased exposure in order to build their brands and audiences. More established news sites will suffer, too, but maybe it’s time for producers of original news to stand on their own and focus on strengthening loyalty bonds with their audiences. It would be better to have Facebook carrying news, but ultimately news outlets need to get beyond their dependence on an uncommitted and often arbitrary partner.

The big question now is whether Google, and perhaps other search engines, choose to accede to the spirit of the Act.

Chris: We’re not the first country to have gone through this. In 2019 and 2020, a good two years before Australia enacted its legislation, France required Google to pay its news media for use of their content. Google removed access to French news in France. The country’s competition watchdog then ruled that this caused unfair harm to the press and amounted to abuse of a dominant market position. Google was forced to the bargaining table and struck compensatory deals with the French news sector.

And Google offers itself as a complete catalogue of Everything in the World right at your fingertips. It’s not a good look for the company if its archives are pockmarked with absences of information just because it happens to be in a dispute with a nation state, or more than one nation state. That would make Google incomplete, untrustworthy, and capricious. Which is counter to its brand. I don’t believe for an instant that Google wants to shut down access to Canadian news. But it does want to have some control over the terms by which it has to pay for Canadian news, and the precedents that might create elsewhere.

Q: What should we make of the criticisms of Facebook during this summer’s extraordinary wildfire season, when the platform refused to allow sharing of news bulletins about the fires in the affected areas?

Ed: The more timely and widely circulated the news, the better. It is a shame in an era of disinformation to curtail access to reliable news. Regardless, the richness of today’s information ecosystem is a thing to behold. When I went on Facebook during the Yellowknife evacuation, I could read the pronouncements of authorities in the Northwest Territories, what the Prime Minister had to say, and, thanks to social media’s unique many-to-many value proposition, receive up-to-the-second reports and images—once known as ‘news you can use’—from people on the ground.

While I couldn’t access organized and trustworthy reporting, nothing stopped me from directly visiting the CBC and CTV sites or cabinradio.ca and globeandmail.com. All in all, I think today’s news consumers should feel more privileged than deprived.

Q: Tell us a little more about the alternative that existed to an Australian-style bargaining code?

Ed: The alternative would have been to impose an explicit levy on the tech companies. That essentially was the principal recommendation of PPF’s 2017 report, The Shattered Mirror: a levy on digital ad sales that would go into a fund to support original news content. There happens to be a handy precedent for that in the form of the Canada Media Fund (CMF). Cable TV, satellite and IP distributors pay a levy of five percent of their revenues into the CMF, which in turn supports the creation of original television and digital content.

At PPF, we’ve since cooled on the concept of a fund, which is slow, unpredictable and potentially opaque. But we have continued to like the idea of a levy. One of the most notable things about the regulations for the Online News Act is that they have effectively embedded a four percent levy into the Australian model, which is why we talk about the final policy now looking like a hybrid. So you get the levy but without the need for a third party to render decisions about how the funds are distributed. In the case of the Online News Act, the funds would be allocated through the obligation for platforms to reach agreements with news organizations. It is a subtle and significant shift.

Q: Is a fund always problematic?

Chris: Not necessarily. It’s just that a fund to support news journalism comes with special problems. In academic research, the government disburses funds through granting agencies such as the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The decisions about who gets funding are taken by expert juries and the process has integrity. Certainly, no one in their right mind would accuse academic research of being tainted by the government or an instrument of government propaganda simply because the funds are allocated to the research councils by the government.

In journalism, as we’ve mentioned, the government created the Local Journalism Initiative to fund reporting positions in what otherwise might be news deserts—mainly small towns and rural areas where the local news media is hanging on by its fingernails. Generally, a fund like that requires some sort of discretionary body that makes the decisions about who gets money and who doesn’t. But if the discretionary body is an agency of the state—no matter how arm’s length it might be—some will argue that it amounts to a form of government control of the news media, once removed. The legitimacy of the granting agency will be under fire from the outset.

In the case of the Local Journalism Initiative, the government handed the funds over to a suite of industry associations to administer, including News Media Canada and Réseau Presse. But that comes with its own problems—the fund is in effect being run by lobbying groups.

Ed: I’d add one kind of structural point against a fund when it comes to journalism. The Canada Media Fund supports time-limited projects—television series, documentary films and the like. They have a scheduled beginning and end. Journalism, in contrast, is an iterative process with no beginning or end. It would be unwieldy and unworkable for the news media to have to apply for funding for every beat, bureau or investigative project.

Newsrooms simply don’t know months or years in advance whether there’s going to be a Hockey Canada scandal or election meddling controversy. Not to date myself, but even Woodward and Bernstein had no idea they were going down a trail that would eventually topple the President.

Q: Do we know how much money the Online News Act might generate and how this compares to what Australia got out of the tech companies?

Chris: The Australian legislation didn’t specify a minimum amount the platforms had to hand over to news organizations, or a maximum for that matter. Although we don’t know for certain since the agreements signed between Google and Facebook and the Australian news media are not public, they reportedly tally on the order of $200 million (AUD), or $174 million. Canada may not be too far off that.

Q: Let’s talk a bit more about the differences between the Canadian Act and its Australian older cousin.

Ed: In the regulations governing the Online News Act, Canada has eschewed Australia’s more laissez-fair design in favour of imposing a number of parameters around how much money the platforms would have to pay and how that money would be allocated.

The Canadian version sets out a formula based on, in the case of Google, global search revenues. These are then divided by Canada’s share of the world economy and then the four percent levy is applied. The government has said the formula produces a figure of $172 million for Google and $62 million for Facebook (should it ever come back to the table) – a total of $234 million.

The formula is curious in that it results in less revenue than one that placed the levy on the amount of advertising revenue the platforms reap from Canada. The government itself reports that 2021 online advertising revenues in Canada totaled $12.3 billion, with Google and Meta accounting for a combined share of 79 percent of these revenues. A 4 percent levy on those earnings would amount to $388.7 million. In its estimate of the revenue potential of the Act, the Parliamentary Budget Officer estimated it would generate $329 million, with three quarters of that going to broadcasters.

It’s quite possible the government felt it could only get Google back to the table at the lower figure.

Q: Is $172 million a significant amount of money for the news business?

Chris: Well, it’s certainly not going to replace the advertising revenue the news business has lost to the digital giants. Today, classified ads in daily newspapers are all but non-existent, but in 2005, at their height, they brought in $875 million, never mind display advertising and ads on news television and radio. Between 2008 and 2021, all told daily and community newspaper revenues plunged by $3 billion—against which $172 million seems paltry.

On the other hand, in 2021 total advertising revenue for daily papers was $541 million, and for community papers $401 million. Against that, $172 million is not insignificant. It could well be the difference between having or losing a newspaper or a broadcast newsroom or even a digital news site in some of the 70 communities affected by the Metroland closures last week.

Ed: Or at least delaying the day of reckoning!

When you ask if it’s a significant sum, I think of what my favourite Succession character, Roman, might say: “Yes. No. Maybe. Who knows.” I agree with Chris that it comes nowhere close to replacing the massive revenue hemorrhaging over the past 15 years. But, as he also suggests, even the $172 million mooted for Google alone can pay for a lot of journalists plus covering other editorial costs.

As things stand now, the Journalism Labour Tax Credit, part of the 2019 aid package, remits 25 percent of salaries up to $55,000 or less back to news operators—or $13,750 a year. While nobody likes the idea of journalist salaries being subsidized, it makes me particularly queasy to imagine outside parties such as the government and platforms carrying more than half the freight. So let’s imagine the platforms match the tax credit benefit. That means the payment to news organizations per journalist would be another $13,750. A $172 million pool divided by $13,750 would support an incredible 12,500 journalists. Even if a quarter of the available funds went to other uses or the $55,000 ceiling was raised, that still assists with something like 10,000 journalists.

Even covering 100 percent of the salary of a unionized reporter in a major Canadian city translates into more than 2,000 journalists—enough to put two people in the newsrooms of every community paper or radio station across Canada.

Q: Well, how many journalists are there in Canada?

Chris: Amazingly enough, for an industry that’s all about documenting the facts of everyday life, we don’t know exactly. Estimates from Statistics Canada, obtained by the National Observer’s David McKie in 2020, suggest there were on the order of 5,100 journalists working in the country—down from 11,600 in 2015. So, if $172 million from Google could help staff up to 10,000 newsroom positions, that would be an enormous contribution to the project of Canadian civic journalism.

Q: Does all this give wealthy platforms too much power over the hard-pressed news media?

Ed: One of my biggest concerns with the Australia model—and we spoke about it at length in The Shattered Mirror: 5 Years On—was that platforms, which are up to their elbows in policy advocacy around taxation, competition, trade and other measures, could be accorded a degree of discretion nobody would accept from a government to pick news industry winners and losers. This is one of the places where the regulations governing the Online News Act really make a difference by essentially preventing the platforms from doing that.

The regulations put in place a number of impediments. First off, news outlets are encouraged to organize themselves into so-called collectives for the purposes of negotiating with a platform. And it obliges the platforms to come to an agreement with any collective of 10 or more independent news businesses (five in the case of Indigenous outlets). One can imagine the members of NewsMedia Canada and the Independent Online News Publishers of Canada forming a collective. Same with broadcasters, minority language publications, small-town media, Indigenous outlets and so on.

Participating platforms do have some wiggle room to avoid outlets that aren’t invited into a collective or choose to stay out. But they cannot avoid many. The regulations stipulate that benefits must accrue to a significant portion of news outlets in smaller size markets; sufficient news outlets in both the non-profit and for-profit sectors, a diversity of business models, local and regional markets in every province and territory, anglophone and francophone communities, Black and other racialized communities and significant portions of Indigenous and minority language outlets.

The collectives produce one related and profound effect. They shift the burden of deciding who gets to share in the proceeds onto the industry itself. So far in Canada, the decision of who qualifies for journalism programs has rested with an independent expert panel selected by the government. That hasn’t been seen as sufficiently arm’s length by some critics. In Australia, it has been left up to the platforms to strike deals with whom they see fit. In the Canadian version of the Australia model, it now will be the news media sector itself that draws the final line between who is in and who is out.

Q: Once you’re in, does every collective get the same deal?

Ed: Not quite, but the Act comes close to leveling the playing field. All deals must fall within 20 percent of the average of all agreements. The act refers to this as the “fair compensation” clause and it is calculated by the compensation per an organization’s number of full-time equivalent journalists. Let’s return to the illustration we used previously of payments from a platform that average $13,750 per journalist. Whether a small news outlet or large, the platform would have to ensure that all its arrangements fall within $11,000 per journalist (-20%) or $16,500 per journalist (+20%).

Chris: That still allows a 200-journalist newsroom to receive 10 times as much as a 20-person newsroom, which is fine because maintaining as many journalists as possible is precisely the problem we are solving for. So who does this favour? Those who employ more rather than fewer journalists relative to their revenues. In fact, it creates something of a carrot to employ more rather than fewer.

Ed: And, by the way, a “full-time equivalent” is not the same, as has been stated in some places, as only full-time employees counting. Two half-timers or four-quarter timers constitute one full-time position. This is important to smaller outlets or start-ups, some of whose staff may not be full-time.

Q: Onto another matter. There has been a lot of chatter that the CBC will gain the lion’s share of benefits. Is this a real cause for concern?

Chris: If the Online News Act was created to save the failing news media in towns and cities across the country, well, the CBC’s not failing—at least not yet. It may be underfunded, it may be politically threatened, but as long as it has that Parliamentary grant the CBC is not in danger of disappearing.

It’s the private sector news media, especially in rural towns and smaller cities, that are fighting to survive, and from the start the Online News Act was described in terms of the crisis in private sector news media. So, if there is private sector rescue money on the table, it seems reasonable to ask if it’s somehow wrong for the CBC to rake up half of it.

On the other hand, if the legislation is built on the insistence that news is a good that platforms trade in and therefore should pay for, well, the CBC produces a significant proportion of Canada’s news content so why shouldn’t it be in line for the same support per journalist as everyone else?

The regulations state that Google would have to enter into negotiated agreements with “a range of news outlets in both the non-profit and for-profit sectors.” That reference to non-profit could mean the CBC. Or it could mean community radio or television stations. A platform is only obligated to negotiate with collectives of 10 or more members. So will CBC find dance partners? I imagine so.

Ed: This is going to be interesting. Traditionally, the unregulated newspaper and digital parts of the business have not mixed easily with the regulated broadcasters, particularly the CBC. Inevitably, there will be charges of double-dipping given the public broadcaster’s $1.3 billion Parliamentary appropriation. At present, the CBC is not eligible for the Labour Tax Credit or the Local Journalism Initiative. But this time broadcasters, including the public broadcaster, have been legislated into the tent. This may become more of a hot-button issue if the Parliamentary Budget Officer is right and the broadcasters could be in line for three-quarters of the available funds.

In Australia, for what it’s worth, both Google and Facebook inked deals with the Australian Broadcasting Corp., which has said the money has allowed it “to significantly expand its regional and rural coverage and network of regionally based journalists” with 57 regional journalists in 19 locations, 10 of them new.” In Canada, there is likely to be resistance from private local news operators to added competition from the CBC.

Also FWIW, public broadcasting doesn’t stand to be the biggest beneficiary of an operative Online News Act.

Q: Then who does?

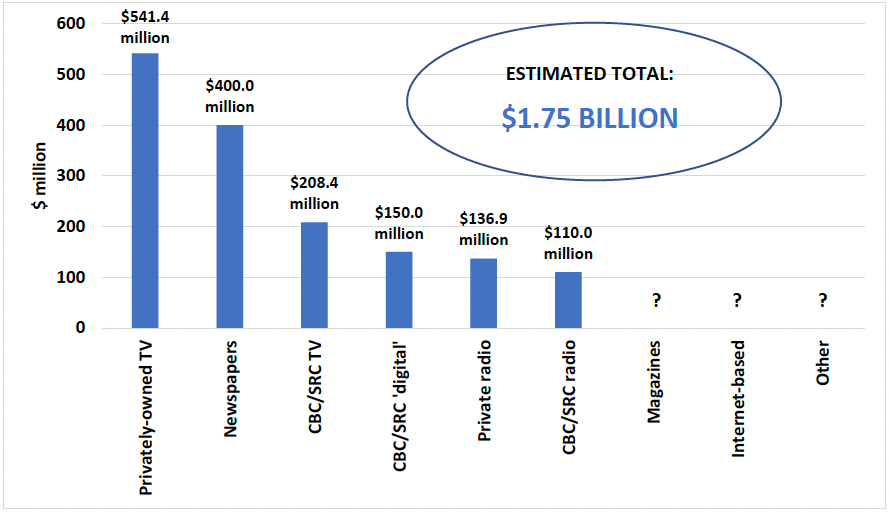

Ed: The private broadcasters. Winnipeg-based Communications Management Inc. has compiled figures from the CRTC, Statistics Canada and various industry pronouncements and come up with an estimate that total media spending on news in 2022 was $1.75 billion. The three biggest contributors were private television ($541.4 million), newspapers ($400 million) and CBC/SRC television ($208.4 million).

Chris: That sheds more light on how big or not the impact of the Act may be. Transfers from Google of $172 million would represent about a 10 percent boost to the entire Canadian news ecosystem.

Estimated total media spending on news in 2022 (Source: Communications Management Inc.)

Q: All this is fine and good, but do we know that the money from these potential deals will actually go to support journalism?

Ed: This is a point on which the regulations are not entirely enlightening. They call for “a commitment from news businesses to use a portion of the compensation received from an agreement to produce news content.” But they don’t say whether a portion is 10 percent or 90 percent. It seems like it will have to be closer to the latter figure in that the regulations also say “the intention is to ensure news businesses are using compensation to invest in Canadian newsrooms.”

Many people will wonder whether a news organization might direct money to executive bonuses or paying down debt? There doesn’t appear to be a direct prohibition. It’s worth noting that the one-year review of the Australian legislation considered this issue and decided that such restrictions could become counter-productive in that sometimes the long-term sustainability of news might be aided by reducing debt.

It is also true that the less attention to employing journalists, the less money available to a news organization. So that creates an incentive of sorts. And the Act calls for the CRTC to retain an auditor to prepare an annual report providing transparency on questions like how the money has been spent. That could provide a disincentive to misdirecting funds. But these are only nudges.

Q: The debate about this Act has been heated. What happens next? What more needs to be done to make sure Canadians have access to a healthy news sector?

Ed: I would say three things are crying out for attention.

- Governance. If public confidence is to be maintained and any apprehension of bias blunted, more work has to be done to maximize the distance between government and its programs in support of news media. There are some interesting models worth examining in Canada and in other countries as well, from our long-standing granting councils to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting in the U.S.

- Innovation, as mentioned earlier, starting with a detailed picture of what the terrain for new business and storytelling models looks like. What is succeeding and what isn’t? The second of our three research questions in The Shattered Mirror asked if digitally based media and communications were filling the gap on civic journalism or could reasonably be expected to do so after a transition period. We asked that question in 2017 and, in truth, we still don’t know the answer.

- Finally, what I would call relocalization. We are circling back to work PPF did in 2018 in a pair of reports called Mind the Gaps and What the Saskatchewan Roughriders Can Teach Canadian Journalism. The first showed how different forms of news coverage were diminishing, the second put forward the case for new business models more heavily rooted in local communities. It is way past obvious that local news, even where it exists, has become too detached from its communities as chain owners centralize news functions in faraway centres.

As crucial as the Online News Act is, it’s only one instrument in what must necessarily be a suite of policy measures, none of which alone can solve this historic radical disruption. Nor should the long-term future of news journalism be permanently dependent on the state.

Let’s not lose sight of what we as a society are trying to achieve. News holds the powerful to account and it builds community. U.S. scholar Michael Schudson has described one of the great functions of journalism as creating “social empathy,” by which he means bringing a compassionate understanding of how different people experience their lives in different ways. In a time of sharpened social divisions, that is surely what policy should be working to promote.

Nobody wants Shattered Communities.