Build Big Things

A playbook to turbocharge investment in major energy, critical minerals and infrastructure projectsSign up to receive our weekly newsletter Build Big Things, a look at all the energy, mining and infrastructure moves fueling the Canadian economy.

By JP Gladu

Founder and Principal, Mokwateh

I am pleased to introduce this important playbook from the Public Policy Forum. It arrives at a crucial moment for Canada. As PPF’s Energy Future Forum notes, our country stands at a crossroads, with an opportunity to rebalance our economy, drive sustainable growth, and meet the pressing demands of a changing world. This is not merely a moment of transition; it is a generational opportunity to redefine our economic landscape and secure a prosperous future for all Canadians.

In my work at Mokwateh, I am dedicated to advancing Indigenous-led prosperity and building durable bridges between Indigenous Nations, governments, unions and industry. As PPF articulates, Indigenous voices are not peripheral; we are central to shaping Canada’s future. The challenges we face — from energy security and infrastructure development to climate action — cannot be solved without meaningful Indigenous partnership and leadership. Our values, our prosperity and our inherent rights are not mere considerations; they are the bedrock upon which a sustainable and equitable future must be built.

The 10 essential plays outlined in this document provide a playbook for prosperity. However, a great playbook requires a great team to deliver success. Unions want jobs for their members; industry wants projects built; and Indigenous communities want to share in the prosperity that we are all working towards. The key will be in how the team will be brought together; it will require a shared understanding that these projects represent win-win-wins. That is how we will build durable partnerships and coalitions for success. Using this playbook, let’s work together, early and often, to build these coalitions for success and reduce the barriers to benefits for all partners.

Last December, the government of British Columbia accomplished something too few governments in Canada have managed in recent years: It got out of the way. The province approved nine new energy projects[1] that included Indigenous equity ownership of more than 25 percent and then shifted the permitting process entirely to the BC Energy Regulator, significantly accelerating development.[2] Several other projects involving transmission lines, mining for critical minerals, and liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports are also being considered for fast-tracking. In May, Nova Scotia announced its own overhaul of project assessments by cutting timelines from over 240 days to just 50 to speed up the province’s transition to clean energy, fight climate change, grow the economy and support sustainable development.[3]

This is how governments get vital projects to the final investment decision (FID) much more quickly.

This crucial moment for Canada is beset by daunting challenges, but also ripe with enormous opportunity. In addition to the immediate threat of a hostile turn toward tariffs and threats of annexation by its primary trading partner, Canada faces significant long-term challenges, including the need to expand energy production to meet growing domestic and global demand, decarbonize its energy system to fulfill international climate commitments, address declining productivity, and strengthen its overall growth trajectory. At the same time, shifts in the global energy mix and the dramatic reconfiguration of the economic and geopolitical order provide a rare chance for Canada to scale up its own ambitions, harness its abundant natural resources, and get its economic house in much better order — tasks that are long overdue.

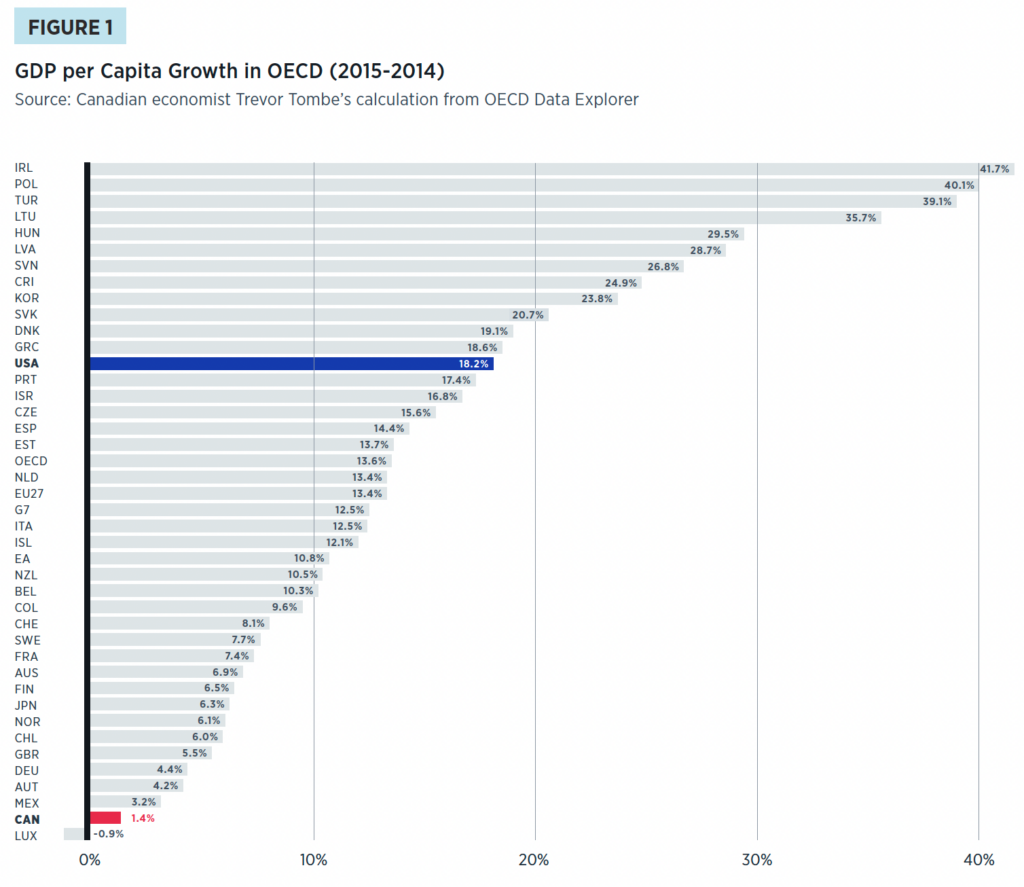

Over the past several decades, Canada has transformed from a production-based economy to one more focused on service and consumption. This has been accompanied by structural economic changes, including stagnating productivity, reduced investment in innovation and capital formation, and lower GDP growth. Canada saw just 1.4 percent growth in real GDP per capita from 2015 to 2024 — even contracting slightly in the last two years — which ranks it second-last among all OECD countries in real GDP per capita growth from 2015 to 2024, beating only Luxembourg.

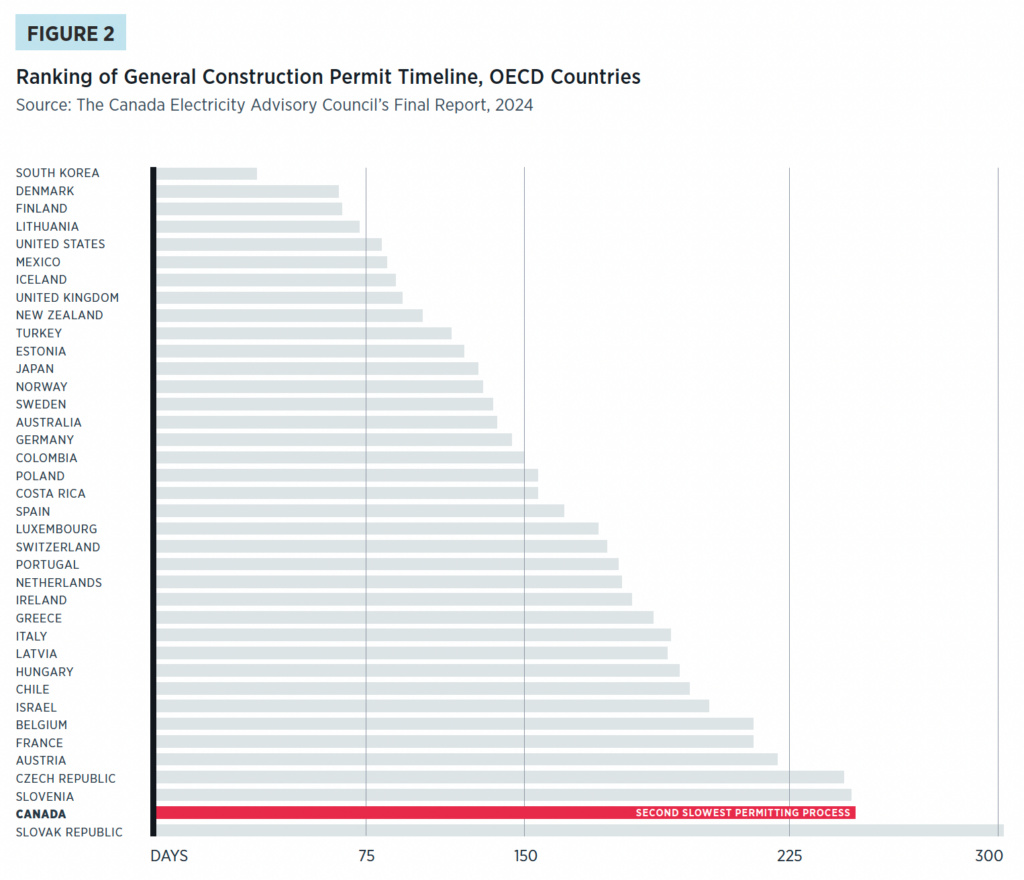

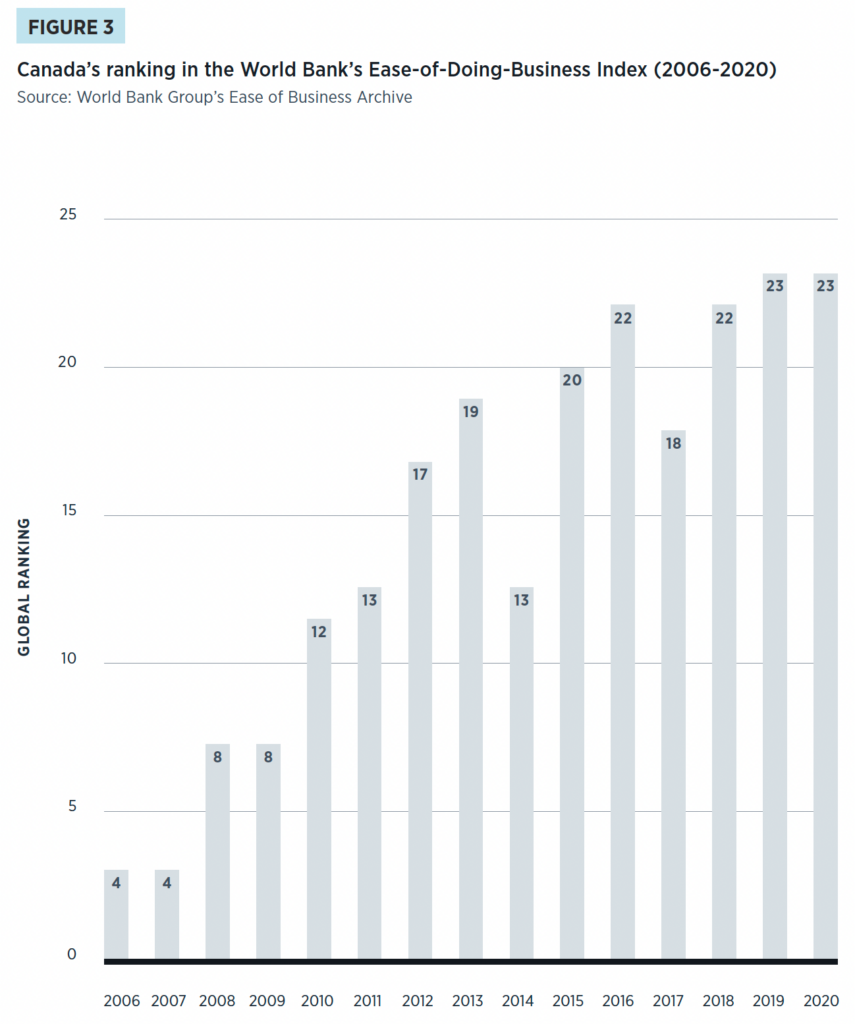

A major cause of this lagging growth is Canada’s bloated regulatory burden. In 2019, the most recent year for which data is available, Canada ranked second worst in the OECD for the time required to obtain a general construction permit. And from 2006 to 2020, Canada fell from fourth place to 23rd place in the World Bank’s ease-of-doing-business rankings.[4]

Canada has been mostly content to muddle along in the slow lane. That’s why British Columbia’s rapid acceleration of clean energy, LNG and mining projects is such welcome news, showing the way for the rest of the country.

Canada will require a breathtaking build-out to tackle its energy needs. An RBC study estimates $2 trillion in new investment will be needed over the next three decades just to overhaul the country’s own energy systems and transition to cleaner energy.[5] We’ll need:

- 77,000 megawatts (MW) of onshore and 5,000 MW of offshore wind power installed capacity. That’s about 30,000 wind turbines;

- 25,500 MW for utility-scale solar, which means 8,500 new photovoltaic solar farms using the industry average of 1-5 MW per utility-scale power plant;

- 23,000 MW of additional nuclear; and

- 40,000 kilometres of high-voltage transmission lines.[6]

As outlined in PPF’s Project of the Century report,[7] powering the country’s expected growth and boosting electrification in service of its domestic emissions-reduction goals and its global climate commitments will require that Canada’s electricity systems alone at least double and possibly triple in size by 2050.

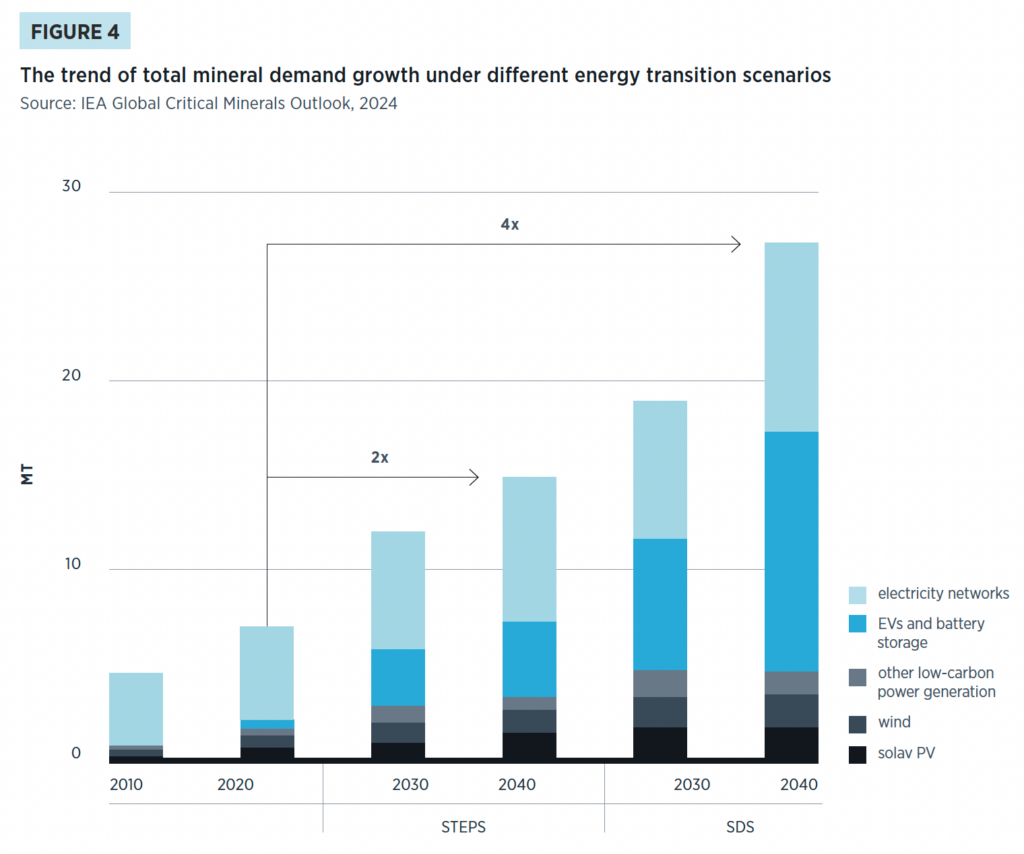

The same is true for critical minerals, where demand is projected to double or even quadruple by 2040 in the International Energy Agency’s Stated Policy Scenario (STEPS) and Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS), respectively.[8] Expanding electricity networks, the buildout of renewable energy sources, and the adoption of new transportation technologies, such as electric vehicles, are far more mineral-intensive than traditional systems.

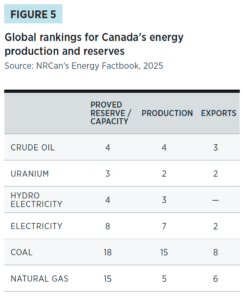

Globally, the demand for critical minerals and energy is also rising — and Canada is well-positioned to help meet it. From electricity and hydrogen to LNG and oil and gas, Canada can supply the full spectrum of energy products and clean technologies — such as CCUS (carbon capture, utilization and storage) and small modular nuclear reactors — that the world needs to drive growth and decarbonization. For example, according to the International Energy Agency, 2024 global energy investment is expected to surpass $3 trillion for the first time, with about $2 trillion allocated to clean energy technologies and infrastructure.[9] Forecasts also project sustained growth in global natural gas demand, along with more moderate but enduring demand for oil and other liquids — reinforcing the strategic case for Canadian exports as a top five global producer.[10]

Canada’s long-term prosperity depends not only on unlocking its vast natural resource potential, but also on building the infrastructure that connects our regions and gets our products to market efficiently. Prioritizing nation-building projects such as ports, rail and roads is essential to strengthening internal economic linkages, enhancing export competitiveness and ensuring supply chains remain resilient and globally competitive. Without modern and reliable trade infrastructure, even the most promising energy and resource projects will struggle to deliver their full economic value. These connective assets are just as vital as the projects themselves — they are the arteries of a productive, growing economy.

Put together, this is a formidable job — but also a once-in-a-generation opportunity to drive economic growth, enhance living standards, restore Canada’s lagging productivity growth, accelerate decarbonization efforts and help fulfill its global climate commitments. A successful transformation must go well beyond incremental tweaks; instead, it will demand co-ordinated public and private sector action to unlock investment and advance high-impact projects, prioritizing new developments that will supercharge the economy by getting our energy and critical minerals resources to the global market and delivering reliable, affordable, low-carbon energy to meet domestic demand and decarbonize our energy systems.

To achieve these goals will require a broad-based approach that PPF has outlined in a “Mission Canada” plan — our blueprint to leverage Canada’s economic advantage, driven by a vision for a Canada that has the stable and growing economy needed to be prosperous amid an increasingly tumultuous geopolitical environment. This approach obliges governments to make firm commitments to co-ordinate their regulations, collaborate on projects of mutual interest and rework outmoded regulatory and financing processes to provide the certainty and market stability that can attract the substantial amounts of capital required for the task.

This playbook for unlocking investment in major energy, critical minerals and infrastructure projects, offers what we believe is the most comprehensive review yet of the policies needed to accelerate projects to FID. Developed through consultations across Canada, it uses the unique policy framework created by PPF to guide those discussions and identify the key barriers that hinder or delay investment.

Policy Framework:

Unlocking Investment and Getting Projects to FID

1. Co-ordinated financing: How can we better align public and private funding sources to support projects and close investment gaps?

2. Efficient and effective regulations: What do we need to do to the regulatory and permitting regime to get projects through the process quicker?

3. Enabling critical infrastructure: How can we take a systems-level approach to planning to ensure that foundational infrastructure and skilled labour are in place to support the building of major projects?

4. Increasing Indigenous economic participation: How can we strengthen partnerships between project proponents, government institutions and Indigenous rights-holders to support meaningful Indigenous involvement in major projects?

Contributors to our analysis included officials representing more than 95 percent of all the energy producers and mining activities in Canada — from renewables and nuclear to oil and gas — along with critical minerals producers, industry associations, Indigenous leaders, and representatives from financial services, civil society, and federal, provincial and territorial governments. We engaged this broad diversity of voices to ensure that this playbook reflects real-world insights, shared priorities and a collective commitment to unlocking investment and getting Canada building again. We also drew on the insights and recommendations from leading organizations and advisory bodies, including the Canada Electricity Advisory Council, the First Nations Major Projects Coalition, the Business Council of Canada and the Canada West Foundation, to name just a few.

We organized this work around working tables on fuels, electricity, critical minerals and regulators, with each focused on a critical piece of the overall plan. We also gathered input from written surveys distributed to dozens of major companies, government institutions and industry representatives. And we assembled an expert advisory committee to provide counsel and contribute critical insights.

Members of this initiative’s expert advisory committee

- Janet Annesley, Chief Sustainability Officer, Kiwetinohk Energy Corp. | Fellow, Public Policy Forum

- Philippe Dunsky, Founder & President, Dunsky Energy + Climate Advisors

- Serge Dupont, Senior Advisor, Bennett Jones

- Karen Ogen, CEO, First Nations LNG Alliance | Board Member, Public Policy Forum

- Peter Tertzakian, Founder & President, Studio.Energy | Founder, ARC Energy Research Institute

Although our diverse cast of experts and stakeholders unsurprisingly sees multiple paths for the future of the country’s resources and economy, there is universal agreement on the importance of accelerating new investment and project approvals to launch a wave of energy, critical minerals and infrastructure growth without recent precedent in Canada.

This is the new national consensus, and we’ve quantified it here for the first time.

We found almost universal agreement among experts on a key element of Canada’s approach to getting major projects to FID quicker: the country has the resources, tools and talent to become the envy of the world in this new economic order. Canada, the saying goes, has everything under the sun it could possibly need — including the sun. Its lengthy list of strategic advantages includes abundant energy resources of all kinds (from fuels to renewables), substantial critical minerals reserves, a highly skilled workforce, a stable political environment, world-class environmental standards and preferential trade access to more than 50 countries (including every G7 nation).

As the world clamours for what Canada has in abundance, these advantages can provide leverage to negotiate new trade arrangements with the United States and compete with other major energy and critical minerals producers and exporters around the world. Canada’s potential for growth is as vast as its resource wealth.

Canada’s critical mineral endowments[11]

Canada ranks fifth in global production of both graphite and nickel and is rapidly emerging as a major supplier of other critical minerals. These resources are vital to the energy transition —particularly in battery manufacturing, where 11 percent of globally mined nickel and 24 percent of graphite were used in 2021. Canada is also well-positioned to contribute to the rising global demand for lithium.

Canada is the world’s leading producer and exporter of potash, a mineral essential for fertilizer production and global food security. In 2021, Canada accounted for 31 percent of global potash production (22.5 million tonnes) and 38 percent of global exports (21.6 million tonnes).

Realizing this potential, however, will require a deliberate rebalancing between consumption and investment in productive capacity, with a tight focus on accelerating the expansion of sectors where Canada holds its greatest strategic advantage, including energy, critical minerals and agriculture. This approach can build a stronger economic future for Canada by maximizing its resource potential, decarbonizing its energy systems, diversifying its export base and positioning it to capture global markets for its resource products.

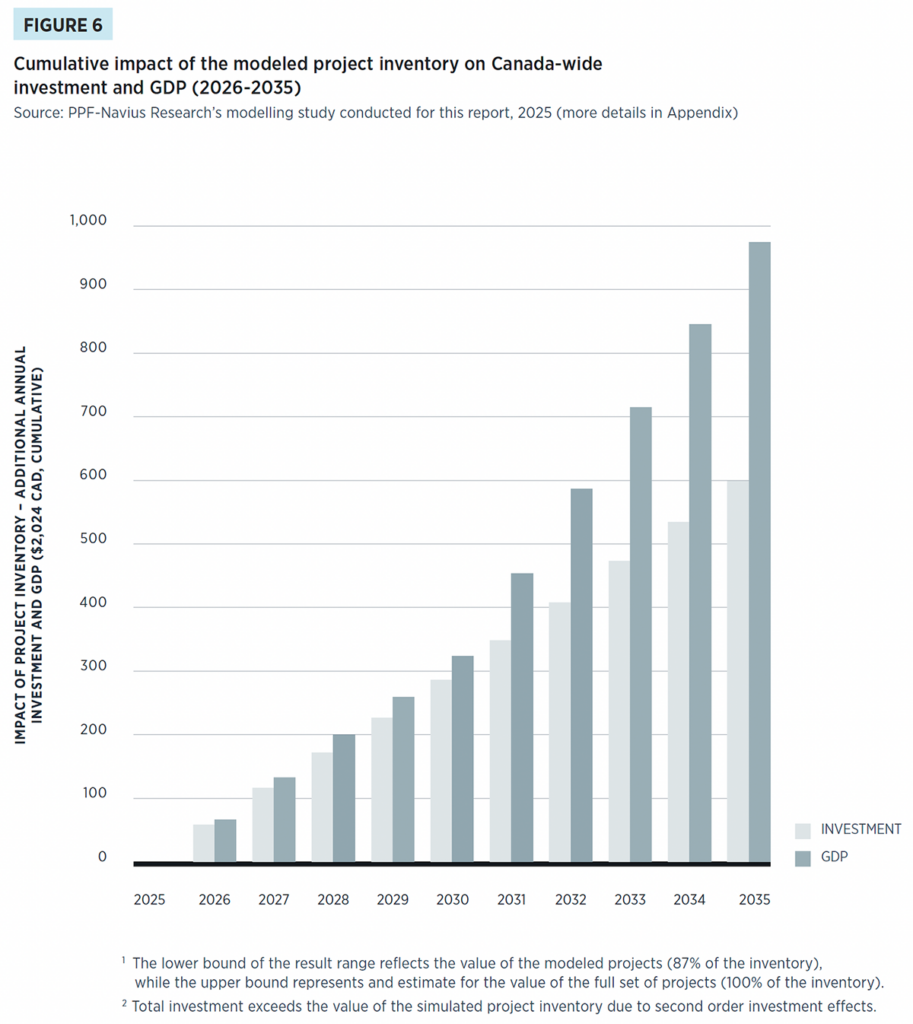

For this report, we examined the economic potential of the current inventory of resource projects already proposed or underway across Canada. Working with Navius Research, we modelled the latest data from Natural Resources Canada’s Major Projects Inventory, tracking more than 500 natural resource projects that are either already under construction or planned through 2034. All told, these projects — spanning clean electricity, oil and gas, mining and clean technologies — represent over $600 billion in potential capital investment. Navius’s analysis found that advancing these existing projects to FID could generate up to $1.1 trillion in cumulative GDP growth, representing a roughly 4.5 percent increase in Canada’s GDP by 2035.[12] This alone would deliver a transformative boost to Canada’s economy, turning energy, critical minerals and infrastructure into engines of long-term growth and propelling Canada’s efforts to become a global powerhouse in energy and critical minerals, including a leader in the low-carbon global economy.

The inward turn of Canada’s largest trading partner and the expansive investments in energy, technology and infrastructure being made in pacesetting jurisdictions, particularly China, are all wake-up calls for Canada. A new economic order is emerging, where Canada’s resource strengths are more valuable than ever. This is the moment for Canada to embrace big ambitions and a comprehensive vision of its place in this changing landscape.

The great game that this report has been drawn up to win is well underway, and the broad array of experts we consulted identified significant weaknesses in Canada’s current game plan, as well as barriers to success that include: burdensome regulatory processes and permitting procedures; insufficient financial supports and difficulty accessing capital, particularly in the crucial, high-risk development stages before getting to FID; inadequate infrastructure such as roads, bridges and ports; and a persistent lack of capacity and capital among Indigenous groups to participate fully as partners in new projects. Officials in one industry after another told us that this approach is a major hindrance to their ability to attract investors and get vital resource projects and infrastructure built.

The proponents of these projects are in urgent need of assistance to navigate the “alphabet soup” of government agencies intended to provide financial and other supports.

Federal funding agencies and programs

- Business Development Bank (BDC)

- Canada Development Investment Corporation (CDEV)

- Canada Growth Fund (CGF)

- Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB)

- Clean Fuels Fund

- Critical Minerals Infrastructure Fund

- Export Development Canada (EDC)

- Indigenous Loan Guarantee Program

- Low Carbon Economy Fund (LCEF)

- Smart Renewables and Electrification Pathways Program (SREPs)

- Strategic Innovation Fund (SIF)

They spoke as well about a maze of overlapping departments, assessments and permitting authorities that can lead to spending more than $1 billion on a large project before it even reaches that all-important FID — and, even then, sometimes only to be cancelled due to shifting political currents. Even though provinces and territories with their diverse energy mixes and needs remain the primary arbiters on crucial questions of permitting, investment and Indigenous participation, projects related to energy, mining and infrastructure in Canada spend three to six years[13] on average in federal regulatory review processes alone. This pace is costing Canadians and frustrating the achievement of their economic and energy needs.

Even in a time of relative economic and geopolitical stability, this would be a significant burden — but this is most definitely not such a time. The United States, China and Russia have asserted themselves as dominant energy and resource forces — the U.S. through sweeping tariffs and market-altering energy orders, China by distorting global critical minerals markets to its advantage, and Russia through its invasion of Ukraine, which has forced Europe to urgently seek alternative sources of supply. Meanwhile, in electricity markets across Canada and around the world, a tectonic shift is underway, driven by the push for clean power and greater electrification, the pursuit of emissions reduction goals, and the impacts of a chaotic new tariff regime. While carbon competitiveness and decarbonization remain priorities, the importance of energy security has emerged with equal urgency.

The winning way forward for Canada on this complex and competitive playing field isn’t through incremental growth and small tweaks to the stalled system governing energy, critical minerals and infrastructure development. Canada needs to announce loud and clear that it is open for business and investment, and ready to set a front-runner’s pace.

At every working table meeting, conference call and informal discussion, we heard why a new playbook was urgently needed. The far more difficult question is how to make it happen.

Our answer begins by organizing our proposed policy actions into four strategic pillars, each one a critical lever for accelerating investment. When implemented together, these pillars create a cohesive, flexible framework to unlock private capital, streamline regulatory processes and enable speedier project delivery.

The four strategic pillars

1. Co-ordinated financing: Align public and private funding sources to support priority projects and close investment gaps.

The issue of co-ordinating financing is not contained in the portfolio of any particular agency or program but rather describes an all-of-government disposition toward project financing. A realignment and co-ordination of policies and agencies between levels of government (federal, provincial/territorial and sometimes municipal) and within each level of government is urgently needed.

Though governments at every level have made admirable efforts to provide financing supports for projects, too often these supports lack clarity and certainty. Processes can be confusing and circular, particularly for new proponents, including Indigenous Peoples and those employing first-of-their-kind technologies. Government agencies and departments can slow processes down while they negotiate among themselves over which is best suited to a given project. And the “alphabet soup” of institutions and programs — particularly at the federal level — needs to be streamlined to provide a “one-stop shop” approach for federal financial support.

Governments should not always aim to be the first or primary source of funding. The most effective role for public financing is often in de-risking projects, particularly in the lengthy, high-risk early phases of a large, long-term project’s path to FID. This includes support for home-grown innovation, first-of-its-kind deployment, or scaling up new technology. Government funding should be provided when a legitimate need has been identified to close the gap between commercial incentives and the public good. Getting projects to FID efficiently requires rigorous analysis to make smart, targeted investments that catalyze companies and private investors — the federal government’s $100 million investment in the Jansen potash mine in Saskatchewan is a good example, having enabled a massive $4 billion project.

While the market should take the lead in driving investment and supplying private capital for major resource projects, governments have a vital role to play in bridging financing gaps. Our framework better co-ordinates the financial supports provided by governments to properly target capital, particularly during the high-risk phase before a project reaches FID.

And while governments can’t expect to entirely de-risk every project, they can send strong signals to the private sector about worthy investments, as well as provide overarching messaging that Canada is open for business. The United Kingdom’s National Policy Statements provide a strong example of how to guide major infrastructure development, outlining national needs and assessment frameworks through statements that are regularly updated and subject to public scrutiny. The 2023 update to the energy statement, for example, clearly articulated how the government would assess various types of energy projects, signaling policy clarity and long-term commitment, which reduced uncertainty for private investors.

Leading jurisdictions around the world can also provide models for de-risking large, long-term projects. The U.K. government’s Regulated Asset Base model, for example, lets project developers recover costs from consumers during construction, providing early revenue and reducing the overall financial risk. Similarly, several U.S. states have used Construction Work in Progress (CWIP) financing to allow utilities to charge customers during the construction of major nuclear projects. Britain’s government has also used a “cap-and-floor” system to guarantee developers long-term revenue certainty while protecting consumers.

An innovative financing tool

Construction Work in Progress (CWIP) is a financing tool that governments are employing to address the considerable upfront costs that must be invested in large projects with long development timelines. CWIP policies allow utilities to charge customers during project construction, providing early capital, decreasing borrowing needs and reducing overall risk. CWIP policies have been used by utilities for capital-intensive nuclear power projects in several U.S. states, including Georgia, Florida and South Carolina. A similar policy has been proposed for the U.K.’s Sizewell C nuclear reactor. This approach helps reduce financing costs, but it does shift some of the burden to consumers before they begin to see the direct benefit of low-cost electricity flowing from a new power plant.

2. Efficient and effective regulations: Reconfigure regulatory and permitting processes to get to “yes” much more quickly, providing clearer timelines, improved efficiency and effectiveness, greater certainty, enhanced environmental performance, and a more strategic role for economic regulators across jurisdictions.

Canada is blessed with some of the most effective environmental protections in the world, and these remain vital to the national interest and the long-term health of the economy. The issue is not regulation itself, but the overall burden of accumulated layers of oversight and regulations.

At present, project proponents and government regulators alike must navigate a complex, overlapping and often confusing set of regulations and applications to get projects to FID. As noted earlier, the federal piece of this puzzle alone stretches from three to six years on average, tying up investment capital for long, uncertain periods.

For large, long-term projects, the approval timeline often stretches across election cycles — a new mining project in Canada, for example, can take anywhere from 15 to 25 years from application to production. This includes clearing the regulatory and permitting process, but other complex factors are also at play — for instance, many potential developments are in remote regions and it takes time for private investors to assess resource potential, determine infrastructure requirements and engage with capital markets. This leaves projects vulnerable to changing political priorities and further amplifies risk for investors. As well, many of the existing regulations are not fit for purpose: they were designed to maintain current energy systems and infrastructure, not for Canada’s upcoming rapid growth and new technology deployment to integrate clean energy sources and reduce emissions.

Our framework streamlines regulatory approval, environmental assessment and the project permitting process to dramatically improve overall timeliness. These processes simply must be made clear, coherent and consistent to provide the confidence investors and proponents require — particularly for major projects with long time horizons and projects that employ first-of-its-kind technology or require regional co-ordination. The European Union’s Projects of Common Interest initiative offers a possible model for multi-jurisdiction regulation, as it provides strong support for key cross-border energy infrastructure (especially electricity transmission) that benefits multiple member states. Denmark’s government, meanwhile, has recently established a “one-stop shop” for permitting clean energy projects that may offer insights into efforts by Canadian governments to streamline their regulatory processes.

A one-stop-shop

The Danish Energy Agency’s “one-stop shop” for offshore wind development provides a compelling model for accelerating major project development. The Danish government established the office in response to criticism from proponents of new offshore wind energy projects, who were encountering bottlenecks in the approval process as they navigated a range of environmental authorities and other regulatory bodies. The Danish one-stop shop co-ordinates the regulatory oversight of seven relevant Danish government agencies, as well as municipal authorities as needed, to create a single coherent and transparent permitting process for offshore wind development.

3. Enabling critical infrastructure: Take a systems-level approach to planning to ensure that foundational infrastructure and skilled labour are in place to support future growth.

No major energy or critical minerals project stands alone. These projects, particularly the largest and most transformative ones, require substantial enabling infrastructure that includes physical assets such as ports, roads, pipelines and transmission lines, as well as the policy tools to attract and retain the necessary skilled labour, encourage trade and support supply chains.

Canada has accumulated a significant deficit in critical infrastructure of all kinds — one report estimated 30 to 50 percent of Canadian infrastructure now requires or will soon need major maintenance work or replacement.[14] Canada’s infrastructure investments since 1990 have hovered around the average of its OECD peers, but spending on transport, energy and utilities has lagged below that average. For example, the Port of Vancouver, Canada’s largest port and a critical gateway for trans-Pacific trade, is currently grappling with significant congestion issues that are disrupting supply chains across North America. There is little value in building infrastructure to ship energy resources to Canada’s coasts if the country’s ports cannot move them along efficiently to global markets.

Government support should include regulatory interventions — perhaps similar to those brought in by the state of Texas, where co-ordinated transmission planning and permitting to facilitate the construction of necessary transmission lines have enabled the rapid development of wind power across the state.

Telescoping permitting processes

As governments look for ways to build enabling infrastructure quickly, the state of Texas’ Competitive Renewable Energy Zones (CREZ) initiative is a successful example of how changes to the permitting process can create dramatic acceleration in electricity development. The state government co-ordinated planning and permitting for new electricity transmission lines in these zones, which enabled rapid development of wind power by connecting high-wind areas in West Texas to major population centres in the rest of the state. Launched by the state legislature in 2005 and approved by the Public Utility Commission in 2008, CREZ has since resulted in the construction of more than 5,500 km of new transmission lines capable of carrying 18,500 MW of power, with the work completed efficiently by competitively selected developers.

These physical infrastructure improvements will also benefit First Nations communities, including improved road access, electrification and communication networks that include cellular phone service and wireless internet.

Unlocking investment in major energy, critical minerals and infrastructure projects is not just a matter of capital and regulatory certainty — it also depends on the timely availability of skilled people. Labour shortages and jurisdictional barriers to workforce mobility have become growing constraints on project delivery, driving up costs and causing delays. Removing interprovincial barriers to labour mobility, particularly for skilled trades and certified professionals such as engineers, is essential to ensure that qualified workers can move freely to where they are most needed. Immediate action to align provincial occupational standards would reduce administrative friction and allow for faster deployment of critical expertise across regions.

At the same time, project proponents must proactively factor labour availability into the early stages of project planning. This means identifying future workforce needs and ensuring that training pipelines, certifications and recruitment efforts are in place before construction begins. Governments, industry and Indigenous organizations should collaborate on targeted training and workforce development initiatives to align labour supply with the specific demands of upcoming projects. This co-ordinated approach will help attract and retain the talent needed to unlock investment and build major “no-regrets” projects at the pace and scale required. These are nation-building projects that respect regional and provincial differences and are aligned with multiple goals, including economic growth and prosperity, energy security, global emissions reductions, and Indigenous economic participation.

4. Increasing Indigenous economic participation: Strengthen partnerships between project proponents, government institutions and Indigenous rights-holders to support meaningful Indigenous involvement in major projects, including through improved access to capital, stronger ownership opportunities and continuous capacity building.

The path to advancing major energy, mining and infrastructure projects in Canada increasingly runs through meaningful partnerships with Indigenous communities and rights-holders. While each project is unique, early engagement and opportunities for economic participation and equity partnerships are essential.

The most crucial aspect of Indigenous participation is the one that has too often been missing in energy, mining and infrastructure projects: mutual trust. As one expert told us, Indigenous participation can only “move at the speed of trust.” The principles of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples can guide governments and proponents alike in advancing positive relationships with Indigenous groups, which will also be situated within the legal frame established under Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 and related jurisprudence.

The federal government’s role in this pillar of the framework is central. As we heard repeatedly in discussions for this report, the Duty to Consult and Accommodate defines a relationship between the Crown and Indigenous rights-holders, and the federal government is responsible for discharging that duty. Yet the current consultation process is often opaque, confusing and poorly communicated — creating uncertainty for both project proponents and Indigenous rights-holders. This leaves both groups uncertain how to proceed and lacking in clarity regarding when the duty has been met.

To be meaningful, however, Indigenous participation must go far beyond the consultation process. An effective way to ensure that a project’s real, material benefits extend fully to Indigenous groups is to prioritize economic participation and equity partnerships. The B.C. government’s fast-tracking of energy projects with a minimum of 25 percent Indigenous equity participation (with at least eight of the projects securing 51 percent equity participation) demonstrates the effectiveness of this strategy. These partnerships require the close collaboration of the private sector and governments in developing strong relationships with Indigenous partners and assisting in building capacity within Indigenous communities. (We note that the federal government has proposed the Indigenous Ministerial Arrangements Regulations, and regulators such as the Impact Assessment Agency and the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission are funding capacity building for regulatory review and project development in Indigenous communities.)

Reliable access to affordable capital to participate in the financing of new projects, as a recent RBC report noted, remains “a persistent challenge for members of Indigenous communities, caused in part by institutional barriers set up by Canadian governments.” Loan guarantees and other financial tools to overcome these barriers have already been introduced and proven helpful, but their rates of implementation have been slow. Current financing tools still leave a capital gap of nearly $50 billion between Indigenous access and potential project needs, putting up to 85 percent of projects passing through First Nations territory at risk.[15]

Financing tools for Indigenous communities

Canadian governments at both the federal and provincial levels have brought in financing tools to assist Indigenous communities with participation in energy and infrastructure projects. These include:

- The federal government’s Indigenous Loan Guarantee Program provides $10 billion to unlock access to the capital needed for Indigenous groups to make major economic investments and has been opened up to sectors outside of energy and natural resources to support more Indigenous infrastructure, transportation and trade projects across the country;

- The Alberta Indigenous Opportunities Corporation, established by the Government of Alberta, provides loan guarantees of up to $3 billion to facilitate Indigenous equity ownership in natural resource and infrastructure projects, including power generation, pipelines, utilities and related infrastructure;

- Ontario’s $1 billion Aboriginal Loan Guarantee Program supports Indigenous equity participation in electricity infrastructure projects, including renewable energy infrastructure and transmission projects, typically providing loan guarantees for about 75 percent of an eligible project; and

- Saskatchewan’s Indigenous Investment Finance Corporation offers loan guarantees of $5 million or more per project to support Indigenous equity in resource and infrastructure projects.

In addition to these loan guarantees, the federal government and the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission are providing direct support for capacity building in Indigenous communities.

At present, too many of these relationships are short term and limited in scope. Project proponents and government agencies need to find ways to extend financing, support and capacity building on a continuous basis.

The most important participants in project partnerships are Indigenous Peoples themselves, who can provide confidence for everyone involved in a project that Indigenous rights are protected and Indigenous communities are receiving real benefits.

With the 2025 federal election now behind us, the new government has a critical window to act. The first 100 days are pivotal — Canada needs a government that hits the ground running with a bold, focused agenda anchored in clear priorities and quick wins. In the face of rising U.S. pressure, decisive action is needed to align government around investment and growth. Every decision must be guided by the imperatives of economic growth, unlocking investment and building faster, smarter and in the national interest.

An effective policy reform package involves a variety of interventions, both large and small, over a range of timescales. Our analysis of how to supercharge this getting-to-FID process has identified 10 essential plays — a new national game plan to align public and private sector action, accelerate nation-building projects and unlock Canada’s full economic potential. With a co-ordinated, cross-sector, multi-jurisdictional effort, Canada can turn opportunities into outcomes and develop the energy, critical minerals and infrastructure needed for a prosperous, sustainable and resilient future.

The government portions of our suggested measures will demand a fundamental, institutionalized cultural shift within the public service, one that rewards public servants for innovation and problem-solving, creates a system where speed, ambition and responsible development go hand in hand, and moves from a mindset of risk-avoidance to opportunity-seeking. It must be embedded in ministerial mandate letters and reinforced through clear leadership and accountability mechanisms. Crucially, this cultural shift will involve reframing how government approaches the impact assessment and permitting process for the “no-regrets” projects. Rather than asking “should we approve this?” regulators should be guided by the question “how can we get this built responsibly and efficiently?”

PPF recognizes that implementing the 10 essential plays will involve real costs and trade-offs. Governments will face difficult decisions about priorities, resources and timelines, particularly in the context of fiscal constraints and political complexity. With thoughtful prioritization and multi-jurisdictional collaboration, these decisions can help unlock the long-term economic potential embedded in Canada’s energy, critical minerals and infrastructure assets.

Here are the 10 essential plays:

1. Accelerate economic growth through a united vision

a. Implement a national game plan to spur economic growth and align public and private sector action to get nation-building projects built more quickly and to turbocharge Canada’s economy.

b. Strike a first ministers meeting to discuss Canada’s growth and investment trajectory, including launching a process to develop a priority list of energy, critical minerals and enabling infrastructure projects.

c. Commit to adopting a federal/provincial/territorial (F/P/T) system-wide approach to advance the four interrelated policy levers (outlined in Chapter 2) in an integrated manner. The goal for first ministers should be to identify efficiencies and synergies that will expedite the policy and legislative changes needed to move projects forward.

d. All levels of government must formally affirm that “Canada is open for business,” backed by concrete actions that will make Canada a globally competitive destination for major project investment and development.

e. The federal government should organize Team Canada missions to Asia, Europe and other potential markets, bringing together other levels of government, industry and Indigenous Peoples to promote Canada’s economic opportunities and competitive advantages.

f. The federal government should send a clear message in its policies and communications that Canada is prioritizing infrastructure, energy and critical minerals development — and that it is ready to partner with industry and governments to attract investment. Start with strong commitments in the Speech from the Throne and Budget 2025.

g. Establish a clear national objective for Canada to achieve real GDP per capita growth rates that place us firmly in the top 50 percent of OECD countries, strengthening our global competitiveness and prosperity. This should be monitored.

h. Set a national goal for Canada to be in the top 10 of the World Bank’s ease-of-doing-business rankings within two years, and to reach the top five within five years.

2. Declare a “no-regrets” projects list

a. Create a national list of major projects deemed “no regrets.” These should be nation-building projects that respect regional and provincial differences and are aligned with criteria that should include:

- Prosperity: Increasing economic growth, employment, affordability and productivity, enhancing competitiveness and investment attractiveness.

- Security: Diversifying export markets in response to the new geopolitical environment, ensuring energy and critical minerals supply, protecting infrastructure integrity for reliability, and ensuring economic and resource sovereignty.

- Environmental responsibility: Contributing to meeting rising domestic and global energy demand through clean solutions that eliminate or significantly reduce emissions while positioning ourselves to win in the post-transition, low-carbon energy economy.

- Reconciliation: Supporting Indigenous ownership and economic participation, meeting Indigenous environmental goals, respecting Indigenous rights and knowledge systems.

b. Complete impact assessment and permitting processes within two years. If the clock runs out, these projects should be deemed approved. While this could be achieved through strong leadership and governance within existing legislation, changes to Bill C-69 and affiliated permitting legislation may need to be considered. Also, project proponents and others involved in the process will need to do their part in providing timely information (including research or studies) required by regulators.

c. Ensure the critical infrastructure needed to enable energy and critical minerals projects is included in this list.

d. Table the list at an initial first ministers meeting on investment and economic growth.

3. Launch a strategic investment office

a. Integrate the four levers noted in Chapter 2 by consolidating financing, regulatory, enabling critical infrastructure and Indigenous consultation functions into a single cohesive office. This will promote a system-wide approach, ensuring coherence in both government policy and funding.

b. Unite under one mission to accelerate the approval of “no-regrets” projects within a two-year window.

c. House the office within a central agency led by a deputy minister and build it mostly with existing resources.

d. Maintain accountability to a cabinet committee on investment, chaired by the prime minister, that provides cabinet approvals and oversees progress.

e. Assign one project team per “no-regrets” project. Staff the teams with experts in financial advisory, resource project planning and development, regulatory and permitting processes, emissions reductions and Indigenous consultation, who are brought in from across the federal government, provinces and territories. Include expertise and capacity to examine projects through the lenses of developers and Indigenous Peoples. Fill gaps in financial expertise with private sector experts in resource project planning and development. Teams should share information and learn from each other with a view to providing consistent approaches.

f. Leverage the Agile project management approach. Enable rapid adaptation, continuous iteration and accelerated decision-making. This includes frequent checkpoints, iterative feedback loops and empowered cross-functional project teams capable of quickly responding to evolving project requirements and stakeholder inputs.

g. Co-ordinate and direct the “no-regrets” projects, including connecting with all the levers and funding envelopes across government to create packaged financing for each project; lead “one project, one assessment” (if not delegated to a province or territory); and co-ordinate the permitting approval requirements and Indigenous consultations to enable getting projects to FID faster.

h. Create a single window for project proponents to submit proposals, including Indigenous consultations. Indigenous groups and industry officials remain confused as to which federal funding agency to engage, as these agencies distinguish between greenfield and brownfield projects.

i. Designate a single Crown consultation co-ordinator for each “no-regrets” project to ensure efficiency of process, effective policy coherence and consistent practices across the federal system (see 5d for details).

4. Get the biggest bang for taxpayer financing

a. Governments can play a vital role in bridging financing gaps to accelerate the path to FID while the market remains the primary driver of investment and source of private capital.

b. Create a single window for proponents to access federal project financing, advisory support and funding tools.

(i) Rationalize and integrate federal financing options (including CIB, CGF, EDC, CDEV, SIF, and SREP) and tax measures (e.g. investment tax credits) to improve coherence;

(ii) Take a disciplined approach to optimizing federal investments by offering customized or packaged financing that blends standard financial tools, starting with lower-cost loan guarantees and then filling gaps with other financing tools, such as grants;

(iii) Provide government funding for “no-regrets” projects to support pre-development project requirements, including project scope and feasibility where necessary, to fill a specific funding gap; and

(iv) Simplify the application process for proponents.

c. Attract and unlock capital.

(i) F/P/Ts should pool resources to create strong market incentives for investment attraction;

(ii) Governments should consider backstopping the “no-regrets” projects to provide financial risk insurance that will attract capital;

(iii) Consider innovative approaches to financing, including crowding in institutional capital and foreign capital;

(iv) Focus on greenhouse gas emissions reduction strategies that minimize costs and support growth and investment. Applying the same cost for each tonne emitted, regardless of sector or region, is more cost-effective than sector-specific measures such as the proposed oil and gas cap. This would create more fiscal room, including for investments in emissions reducing technologies, such as carbon capture, sequestration and storage;

(v) Private capital markets should lean in and share the risk by taking a more active role in unlocking investment and helping to de-risk major projects; and

(vi) Governments must market Canada as a competitive destination for foreign direct investment.

d. Consider tax measures in the optimization of the overall policy mix, for example:

(i) Reduce the effective tax rate on new investments and capital gains;

(ii) Allow a 100 percent exemption on capital gains taxes payable if the proceeds are re-invested into another asset within 12 months; and

(iii) Exempt all profits invested in new capital, machinery and equipment from taxation. Only distributed profits should be taxable.

5. Speed up and de-layer regulatory and permitting approvals

a. Provide faster regulatory approvals and permitting. Remove overlap and duplication, while continuing to uphold the highest environmental standards and respecting Indigenous perspectives on the traditional use of air, water and land. For example, regulatory and permitting overlap, including environmental regulations, currently impedes the development of clean energy projects needed to achieve Canada’s climate commitments.

(i) Implement a “one project, one assessment” approach for all projects. Substitute provincial/territorial/Indigenous environmental assessment processes where possible;

(ii) Streamline the regulatory and permitting approvals process to reduce approvals timelines to two years (as noted in Play #2), with no stop clock. B.C.’s approach provides a good example;

(iii) Reduce regulatory scope where feasible, promote regional environmental assessment to accelerate project-level assessments and reduce duplication so that individual projects don’t need to review the same data, and apply other tools to lessen the burden on project proponents; and

(iv) Administer impact assessment and permitting processes concurrently to support efficiency.

b. Create certainty of process. Clearly map out the approvals process up front to provide clarity and build trust and confidence with project proponents (for instance, Ontario Power Generation took this approach for its small modular reactor projects). Once a decision is made to proceed with a project and a permit is issued, the decision should not be overturned.

c. Reverse the cumulative regulatory burden to restore Canada’s competitiveness for investment. Even the best impact assessment process won’t help if new layers of regulation, at all levels of government, continue to add cost, complexity and uncertainty.

d. Designate a single Crown consultation co-ordinator for each “no-regrets” project.

(i) Ensure consultations begin as early as possible in the project development process;

(ii) Expedite processes where there are existing rights-of-way on previously approved projects;

(iii) Build on the regulators’ relationship with Indigenous organizations where projects have already been constructed to continue to strengthen long-term relationships and trust.

e. Ensure regulatory stability, including regarding when changes in government occur.

(i) Enshrine the two-year streamlined project approval and permitting process in legislation by amending the governing statutes of regulatory and permitting departments and agencies to mandate efficiency, co-ordination and clear timelines. If these timelines are not met, these projects should be deemed approved. Explore making the needed changes through one omnibus piece of legislation included in the first Budget Implementation Act of a new government; and

(ii) Change the legislative mandates for regulatory authorities (e.g., Canada Energy Regulator, Impact Assessment Agency, Transport Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada) to take into account economic and investment factors in the permitting process.

6. Advance meaningful opportunities for Indigenous economic participation

a. Build long-term relationships.

(i) Governments, industry and regulators need to take a long-term view in building relationships with Indigenous rights-holders and communities to earn trust and confidence;

(ii) Indigenous rights-holders and communities must be involved early and at every stage of the project development process; and

(iii) Indigenous participants and partners should be empowered to collaborate with neighbouring Indigenous rights-holders and communities.

b. Create opportunities for equity ownership. Governments should prioritize projects that have meaningful Indigenous economic support and/or participation and/or partnership (for example, revenue sharing, jobs and procurement, and equity partnership. B.C. required a minimum of 25 percent Indigenous equity for projects to qualify in the 2024 Call for Power). Equity ownership by Indigenous Peoples also needs to be considered across the value chain, including shipping and infrastructure.

c. Accelerate access to capital.

(i) Speed up efforts to provide Indigenous governments and their corporations affordable access to the capital needed to take meaningful equity stakes in projects; and

(ii) Expedite the federal Indigenous Loan Guarantee Program and mandate it to support Indigenous equity investment in all project stages, including riskier early-stage equity investments. Consider expanding the program to include direct loans (for example, for bridge financing or riskier equity investments that are better suited for public support).

d. Enable Indigenous investment in all project stages, including the earliest stages when Indigenous partners have the best opportunity to add value and shape a project’s outcome.

e. Continue to build on the effective practice of establishing joint Indigenous monitoring committees to directly participate in environmental oversight and monitor project impacts in real time throughout the life cycle of energy projects — strengthening trust, transparency, and reconciliation through shared stewardship.

f. Provide employment, training and skills development. Develop initiatives to ensure Indigenous individuals and communities are equipped to secure employment related to major project development, including skills development to obtain the Red Seal for trades. For example:

(i) Fund pre-employment and job readiness programs in host communities in advance of construction activities and focus on certifications and licensing; and

(ii) Establish Indigenous employment targets for major projects during construction and operations (e.g. 25 percent of the workforce), with reporting and enforcement mechanisms tied to project milestones or public funding support.

g. Increase opportunities for procurement, contracting and business development. Ensure Indigenous businesses are first out of the gate for higher value procurement in building major projects. For example, establish dedicated procurement/contracting processes that maximize Indigenous business participation in major project development, such as including a requirement for a detailed Indigenous procurement plan with established partners, scopes of work and dollar value commitments that form part of the evaluation criteria for awarding contracts.

7. Align critical enabling infrastructure (physical structures and people)

a. Prioritize and rank critical infrastructure projects.

(i) Align with the agreed-upon project selection criteria (noted in 2a) and regional support and include in the “no-regrets” project list;

(ii) Develop an inventory of priority economic infrastructure;

(iii) Explore the establishment of pre-approved critical infrastructure corridors for long linear infrastructure, such as pipelines and transmission lines;

(iv) Take regional approaches where appropriate; and

(v) Consider government ownership (e.g. a merchant line) or user-pay models to accelerate development and enable projects that may not be economical.

b. Pursue an integrated F/P/T approach. F/P/T collaboration is a must to address project needs, to determine investible projects and to identify infrastructure and labour requirements early in the project development process.

c. Promote the availability of labour.

(i) Eliminate all federal and provincial barriers to interprovincial labour mobility and ensure the skilled labour and certified professionals (e.g. engineers) are available to enable the build. For example, immediate action should be taken to align provincial occupational standards;

(ii) Project proponents should ensure labour requirements are taken into consideration in the early stages of project planning so that skilled labour and certified professionals are available to enable the build; and

(iii) Align labour markets with the needs of new projects through specialized training and partnerships between government, industry and Indigenous organizations to attract talent and ensure it is available.

8. Develop Canada’s vast critical minerals

a. Prioritize critical minerals needed for Canada’s and the world’s transition to low-carbon energy, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper and “rare earth” elements.

b. Increase F/P/T collaboration to pool funding to build the critical infrastructure needed — such as roads, rail, ports and cost-effective low-carbon energy sources — to access remote and northern deposits on a priority basis (e.g. Ontario’s Ring of Fire).

c. Boost funding for critical minerals exploration and development by broadening the scope of government tax incentives and financing programs to explicitly include critical minerals.

d. Support R&D and innovation for value-added processing in Canada to capture the full value of critical minerals and ensure reliable supply.

e. Offset price signal distortions caused by China’s market dominance by providing:

(i) Government support such as direct equity positions or long-term offtake agreements;

(ii) Government purchase agreements (e.g. contracts for difference) to provide a minimum price floor to establish revenue certainty and mitigate price fluctuations; and

(iii) Establish government-managed strategic minerals stockpiles (possibly co-ordinated with allies) to guard against physical shortages and wild price swings.

f. Identify and integrate labour requirements very early in project planning to accurately estimate capital and operational expenses and ensure labour availability, predictability and cost.

g. Plan collectively and pro-actively, on the part of governments and industry, to ensure labour availability in time to achieve FID and build these projects. This includes removing barriers to immigration and foreign credential recognition for professionals.

9. Forge strong partnerships and build trust

a. Expand the use of public-private partnerships (P3s) to co-finance and co-deliver major infrastructure projects, leveraging private capital and expertise to advance these projects, as well as to enable economic resource projects on the “no-regrets” list.

b. Federal and provincial governments should commit to moving forward together with a sense of urgency and common purpose, using formal mechanisms such as first ministers meetings, the Council of the Federation, the F/P/T Energy and Mines Ministers Conference, and intergovernmental agreements to ensure all levels of government and key partners are accountable for accelerating timelines, removing roadblocks and delivering on the shared goal of unlocking investment and advancing projects to FID.

c. Deepen Indigenous and local partnerships by building long-term, trust-based relationships through early engagement and meaningful economic participation, including equity ownership, procurement opportunities and community benefit agreements.

d. Improve intragovernmental co-ordination by including provincial and territorial representation within the proposed Strategic Investment Office — enabling faster decision-making and joint problem-solving on the co-ordination of project financing, regulatory and permitting challenges, Indigenous economic participation and workforce development.

e. Engage municipal governments early in the process to align on timelines, identify and address local barriers — such as permitting, zoning and regulatory requirements — and co-ordinate the development of enabling infrastructure like roads, utilities and worker housing. Early collaboration helps de-risk projects, streamline approvals and accelerate the path to FID.

f. Act quickly on key recommendations in this report to deliver early wins that build trust, demonstrate momentum and send a clear signal to investors that Canada is serious about getting major projects built.

10. Stay laser-focused with mission-driven accountability

a. Establish a cabinet committee on investment, chaired by the prime minister, to oversee progress on the “no-regrets” project list and provide cabinet approvals.

b. Create a deputy ministers committee that meets monthly and is responsible for making decisions and delivering on project list approvals within a two-year timeframe. Ensure collective accountability through performance agreements.

c. Hold first ministers meetings quarterly to review project progress and remove interprovincial barriers.

d. Use dashboards, public reporting and milestone tracking to measure momentum and maintain focus.

Getting major projects in Canada’s national interest to FID more quickly will require strong leadership at every level. It will mean collective commitment from the prime minister, premiers, industry leaders, environmental advocates and Indigenous partners. It will take a shared sense of urgency and common purpose.

And it will demand boldness — courage, even — to choose common ground over competing interests.

If we can unlock urgent investments for energy, critical minerals and major infrastructure projects, and we can, we’ll deliver enormous dividends for Canadian citizens.

We’ll drive prosperity, with a more competitive investment environment, returning this country to the top of global economic growth and prosperity charts with higher GDP growth, employment and productivity.

We’ll enhance Canadian energy and critical mineral supply security, with a reduced reliance on trade with the United States via diversified export markets and strengthened critical infrastructure.

We’ll promote environmental responsibility, positioning Canada for success in the low-carbon economy by meeting rising domestic and global energy demand through technological solutions that eliminate or significantly reduce emissions, while demonstrating the highest environmental standards.

And we’ll advance reconciliation, centring meaningful Indigenous rights and knowledge systems in project development and enabling Indigenous rights-holders to lead and benefit directly from economic development and environmental stewardship.

We’ve delivered a playbook to accomplish these goals, but we also recognize that this is far from being just a game. The future of our country may well depend on it.

Clear eyes. Full hearts. Can’t lose.

Navius Research Modelling Study: Quantifying the economic benefits of the NRCan Major Project Inventory

Methodology

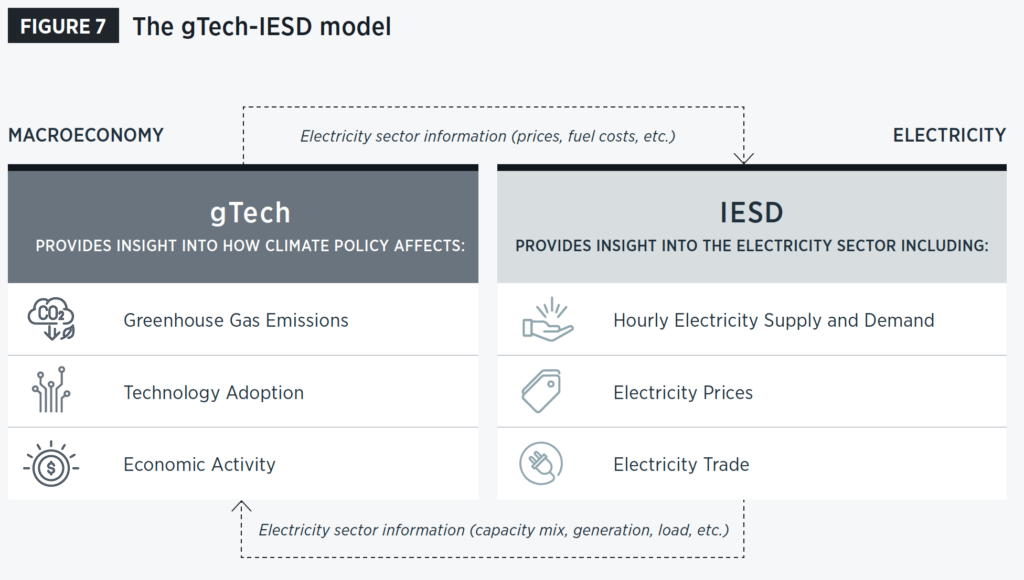

Navius used its gTech-IESD model (Figure 1) to simulate the impact of the NRCan Major Project Inventory. The scenario analysis involves comparing the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and investment impacts of two scenarios in five-year increments out to 2035:

1. Counterfactual scenario, in which no projects on the NRCan inventory come to fruition between 2026 and 2035; and

2. Project list scenario, in which all projects on the NRCan inventory are realized between 2026 and 2035.

Scenario development

The value of total investment in the project inventory exceeds $600 billion (2024 CAD) and spans a multitude of sectors, including mining, oil and gas, electricity, and clean technologies.

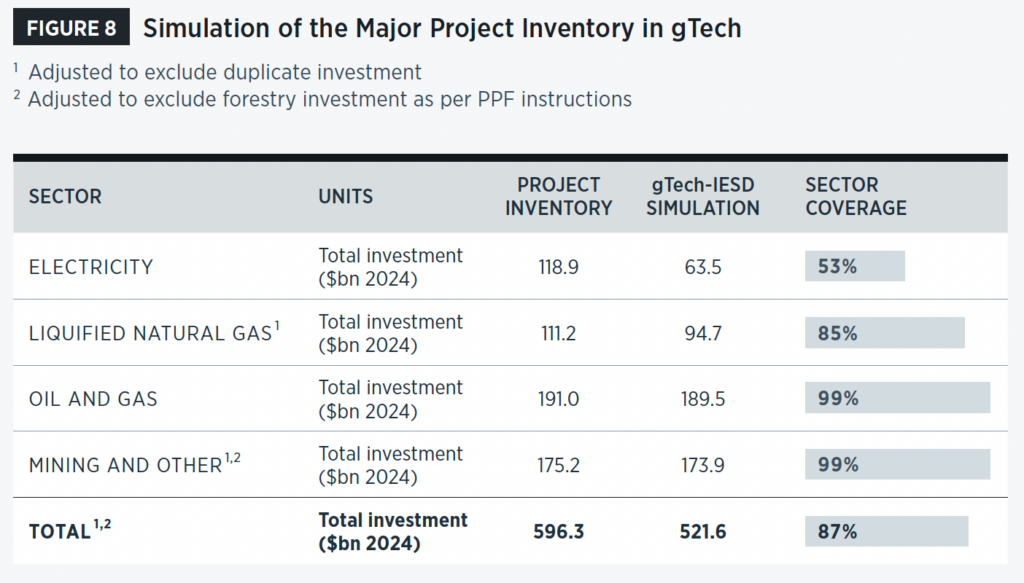

Navius parameterized the list of projects in the 2024 NRCan Major Project Inventory into its gTech-IESD model. Table 1 below summarizes Navius’s parameterization of the inventory in gTech-IESD by sector. The modelling includes broad coverage of all key sectors, with Navius successfully simulating 87 percent of the project list by project value.

Certain projects were not explicitly modelled in this exercise, such as those in the forestry sector. Sectors that are particularly reliant on demand-side growth, such as electricity and hydrogen, were solved for endogenously, i.e., Navius allowed for sector activity to grow in response to demand, rather than forcing in additional supply of these commodities. More information on this approach is available in the caveats and considerations section.

Key insights

Insight 1: Actualizing NRCan’s Major Project Inventory would create a step-change in capital investment in Canada. The inventory captures over $600 billion of potential capital investment in energy, mining and electricity projects, which over 10 years would be roughly equivalent to 10 percent of the entire capital formation of the country.

Insight 2: The economic activity spurred by the project inventory over the next 10 years could be 1.6 times the value of the upfront investment. The value of the project inventory extends beyond the direct investment as it drives second order increases in investment, output, exports and domestic consumption.

Insight 3: While the potential value of the project inventory is clear, there is no guarantee that regulatory approval will bring all projects to fruition. Certain projects will only be viable if sufficient demand exists for them, even if they make it through regulatory approval. Hydrogen production and electricity generation projects are key examples of this trend, where the project economics are best if they are driven through “demand-pull” rather than “supply-push.”

Caveats and considerations

Results of Navius’s modelling of the NRCan Major Project Inventory should be interpreted alongside the following caveats and considerations:

- This analysis did not consider the impact of changes to federal or provincial project approval regulations. This analysis shows the value of the project inventory, but it does not indicate whether these projects will be economically viable if they are ultimately approved. Navius forced a certain level of sector activity into the gTech model to represent the inventory going ahead, not the value of removing red tape.

- Some projects in the inventory will only exist in a world where external demand materializes. Navius allowed activity in select sectors to respond endogenously to demand instead of prescribing a certain level of activity. These sectors include:

Hydrogen production — building a dedicated hydrogen export sector to international markets was beyond the scope of this project, which was the basis for various projects contained in the inventory. Forcing this production into the model without the export market would have created issues in the market for hydrogen and led to a drag on economic activity.

Electricity generation — forcing a certain level of electricity capacity can lead to an outcome known as “gold plating,” where the system is built out beyond requirements. This dynamic can lead to artificially higher electricity prices, as the utility must recover higher system costs over the same (or smaller) number of rate payers, which can slow economic growth.

- A full review of the project list was outside the scope of this analysis, meaning some project duplicates may have been included. Navius identified and removed several projects, such as two duplicates of the Ksi Lisims LNG proposal (IDs 1037, 4125 and 5014), meaning the targeted level of investment was lower than the gross total inventory. However, the projections provided here may have included other duplicate projects in the inventory.

- The upper bounds of the GDP projections use a linear extrapolation of the modelled GDP trend. Navius extrapolated the GDP impacts of the modelled projects to estimate the value of the full inventory. The true impact of the full project list may be lower than the projection, since impacts could be diminishing in nature. In addition, crowding out of investment and consumption can occur at high levels of investment, which could further contribute to lower levels of GDP than projected.

PPF acknowledges all the partner organizations and their representatives who informed the analysis and arguments in this report. For the full list of partners for PPF’s Energy Future Forum, please refer to the project’s webpage.

We would also like to recognize the valuable contributions of the members of the advisory committee for this initiative, who shared their expertise and insight throughout the process:

- Janet Annesley, Chief Sustainability Officer, Kiwetinohk Energy Corp. | Fellow, Public Policy Forum

- Philippe Dunsky, Founder & President, Dunsky Energy + Climate Advisors

- Serge Dupont, Senior Advisor, Bennett Jones

- Karen Ogen, CEO, First Nations LNG Alliance | Board Member, Public Policy Forum

- Peter Tertzakian, Founder & President, Studio.Energy | Founder, ARC Energy Research Institute

- Office of the Premier. (Dec. 9, 2024). New wind projects will boost B.C.’s affordable clean-energy supply. Government of British Columbia. https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2024ECS0048-001643 ↑

- On April 30, 2025, Energy Minister Adrian Dix introduced Bill 14, the Renewable Energy Projects (Streamlined Permitting) Act, in the B.C. legislature. If passed, the legislation would put the BC Energy Regulator, which oversees oil and gas operations, in charge of renewable energy projects as well. The regulator would also oversee major new transmission lines, including the North Coast transmission line, to power liquefied natural gas (LNG), mining and other projects. On May 1, 2025, BC introduced Bill 15 (the Infrastructure Projects Act) that would give greater powers to the Cabinet to expedite the approval of projects it deems a matter of provincial significance. If passed into law, it will allow the minister responsible for a specific infrastructure project to make decisions to facilitate the completion and operation of the project as expeditiously as possible. ↑

- Nova Scotia Environment and Climate Change. (May 8, 2025). Environmental Assessment Changes Reinforce Commitment to Fight Climate Change, Move to Clean Economy. Government of Nova Scotia. https://news.novascotia.ca/en/2025/05/08/environmental-assessment-changes-reinforce-commitment-fight-climate-change-move-clean ↑

- World Bank. (Oct. 24, 2019). Doing Business 2020. https://archive.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2020 ↑

- RBC Thought Leadership. (Oct. 20, 2021). The $2 Trillion Transition: Canada’s Road to Net Zero. https://thoughtleadership.rbc.com/the-2-trillion-transition/ ↑

- Golshan, A. (Mar. 27, 2024). A Hurry-up Offense for Energy Transition and Clean Growth Projects. Public Policy Forum. https://ppforum.ca/publications/energy-transition-clean-energy-growth/ ↑

- Annesley, J., Campbell, D., Golshan A., and Greenspon, E. (July 19, 2023). Project of the Century. Public Policy Forum. https://ppforum.ca/publications/net-zero-electricity-canada-capacity/ ↑

- International Energy Agency. (2021). The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions ↑

- International Energy Agency. (2024). World Energy Investment 2024. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2024 ↑

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. (Oct. 11, 2023). International Energy Outlook 2023. https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/ieo/ ↑

- Minister of Natural Resources. (2022). The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/campaign/critical-minerals-in-canada/canadian-critical-minerals-strategy.html ↑

- Further details about the methodology of this modelling study, which was conducted exclusively for this report, can be found in the appendix. ↑

- Drance, J., Cameron, G., and Hutton, R. (Sep. 2018). Federal Energy Project Reviews: Timelines in Practice, 6(3). Energy Regulation Quarterly. https://energyregulationquarterly.ca/articles/federal-energy-project-reviews-timelines-in-practice#sthash.v6HGJEnQ.7bciQpqe.dpbs ↑

- Smith, D. and Halliday, K. (January 2020). 15 Things to Know About Canadian Infrastructure. BCG https://www.bcg.com/15-things-to-know-about-canadian-infrastructure ↑

- Srivatsan, V. (Apr. 22, 2025). Building Together: How Indigenous economic reconciliation can fuel Canada’s resurgence. RBC Thought Leadership. https://thoughtleadership.rbc.com/building-together-how-indigenous-economic-reconciliation-can-fuel-canadas-resurgence/ ↑