The Missing Article

How to get Canada back in the game on Article 6Introduction

Rarely does one encounter a policy so beguiling, yet so difficult to grasp, as the 6th article of the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. It is the section of the treaty that allows the parties “to pursue voluntary cooperation” — the transfer of emissions credits — in reaching their nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Recognizing that governments cannot solve the problem alone, Article 6 enlists markets, with their special talent for efficiency and innovation, to the cause. At a point when we are seeing growing resistance to the costs of the energy transition, it is estimated that such voluntary co-operation can cut that burden in half.

For obvious reasons, the Paris negotiators placed the responsibility for tackling global emissions on individual sovereign nations. But how to get them to work together through trade and investment, either bilaterally or multilaterally, for mutual benefit and a greater overall result? Article 6 provides the necessary encouragement for Country A to bring its advantages to bear on Country B’s emissions reductions. Simply put, Country B, where a mitigation act would occur, could enter into an agreement with the enabling Country A to transfer some share of those emissions reductions — called Internationally Traded Mitigation Outcomes or ITMOs — from one national balance sheet to another. There would also be multilateral vehicles.

For a technologically advanced and well-regulated energy-exporting nation like Canada, Article 6 remains as enticing as it is elusive. Nowhere is this more pronounced than in Canada’s two most westerly provinces, home to some of the world’s most abundant and least carbon-intensive natural gas formations and world-leading methane reduction innovations. Those involved in developing these deposits — governments, corporations, First Nations — wonder, not unreasonably, why Canada should not be in line to receive ITMOs if the cleaner Canadian gas displaces the burning of higher emitting coal in Asia.

In recent years, there have been calls for Canada to take a greater leadership role in the shaping of Article 6 — a multilateral role that this country has already played in the founding of the G20 in the late 1990s, the creation of the Cairns Group of agricultural exporting nations in the mid-1980s and in advocating in the 1970s for adoption of a 200-mile economic exclusion zone within the Law of the Sea convention.

For now, though, it is an importing nation, Japan, that has taken the initiative to establish an Article 6 implementation partnership to “stimulate decarbonization markets and private investment.” Launched in late 2022, it now has 69 members, including Canada.

The Public Policy Forum has a long-standing interest in Article 6 as a means of facilitating emissions reductions. We wrote about its potential contribution in a 2021 report setting out a low-carbon export strategy for Canada.[1] In our discussions with decision-makers in government and industry, we tend to encounter three distinct perspectives: those who consider international collaboration on emissions trading some kind of dodge on national responsibility; those who believe the answer is out there somewhere and continue to plug away at how to operationalize Article 6; and those who despair of requirements that they feel render implementation all but impossible.

It is for each of these categories of interlocutors that we commissioned this report, The Missing Article. PPF asked a widely recognized trio of Canadian subject matter experts to explain why Article 6 exists, where it currently stands and how Canada could make use of it for the national advantage and global good. We hope it will stimulate discussion around this important tool in the world’s emissions-reduction arsenal.

Edward Greenspon, President and CEO, Public Policy Forum

Chapter 1: The Urgent Climate Challenge and the Daunting Cost of Global Energy Transition

The climate context for this report is made increasingly apparent with each passing summer of record heat waves, wildfires, floods and melting ice. Global surface temperatures are already 1.1°C higher than pre-industrialization levels,[2] as policies and laws previously announced to address greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reductions remain inadequate to achieve the temperature targets of the Paris Agreement.[3] The International Energy Agency estimates that net-zero emissions pledges now cover approximately 90 percent of global GDP and 85 percent of global energy-related emissions.[4] However, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that pathways to achieve our temperature goals still require “rapid, deep and, in most cases, immediate emission reductions.”[5] As things stand, the world’s emissions trajectory is projected to result in an increase in global temperatures of between 2.4°C and 3.2°C[6] over the pre-industrial age, leaving a gap between expected global emissions in 2030 and the level needed to limit warming to 1.5°C (or even 2°C), equivalent to nearly 3.8 times the annual total GHG emissions of the United States.[7] Canada also appears to be contributing to that gap and is not on track to meet its Paris Agreement targets of a 40-45 percent reduction from 2005 emissions levels by 2030.[8]

The IPCC points to widespread and significant evidence of extreme impacts being experienced today, such as intense heatwaves, heavy precipitation, droughts and tropical cyclones that have been directly attributed to human influence from the burning of fossil fuels and the associated rise in GHG emissions.[9] In addition, climate change has caused substantial and likely irreversible losses and damages in terrestrial, freshwater, cryosphere, and coastal and open ocean ecosystems, with the extent and magnitude of these impacts larger than previously estimated.[10]

The Daunting Cost of Global Energy Transition

The cost of the inescapable net-zero transition could be as high as US$275 trillion ($9.2 trillion/year) in cumulative spending by various sectors of the economy between 2021 and 2050, or about 7.5 percent of global GDP.[11] The International Energy Agency estimates that annual clean-energy infrastructure investment globally will need to more than triple by 2030, to approximately US$4 trillion per year, in order to reach its net-zero emissions by 2050 pathway.[12] In Canada, the Royal Bank has conservatively estimated that governments, businesses and communities will need to spend approximately $2 trillion ($60 billion/year) over the next three decades to decarbonize our economy.[13] In its last budget, the federal government forecast the cost at $125 billion to $140 billion a year, which translates to a $3.5-trillion price tag. These conservative estimates also assume that: there is no further delay in the required GHG mitigation and adaptation actions; high-emissions power plants and pipelines are not entrenched; and anticipated climate loss and damage do not exacerbate the costs.[14]

The costs of inaction or inadequate action are already being felt and will only get worse. As we are seeing when climate action intersects with the affordability crisis, the toll from sub-optimal policy responses is economic and political — and significant in both instances. The world needs the most orderly and least costly energy transition possible. The approach needs to minimize pain to the economy generally and to vulnerable consumers in particular, to facilitate investment in the energy transition, and to accelerate resulting emissions reductions and removals.

Canada was a key leader in crafting Article 6 at Paris but has often been missing in action since. This paper puts forward the proposition that it is time for Canada to join those nations leaning on the role of market forces in optimizing the energy transition. Pick your metaphor: we need to use all tools at our disposal; we need all hands on deck; we must leave no stone unturned. There is a reason Article 6 is part of the Paris Agreement, and a compelling case now for it not to become its forgotten stepchild.

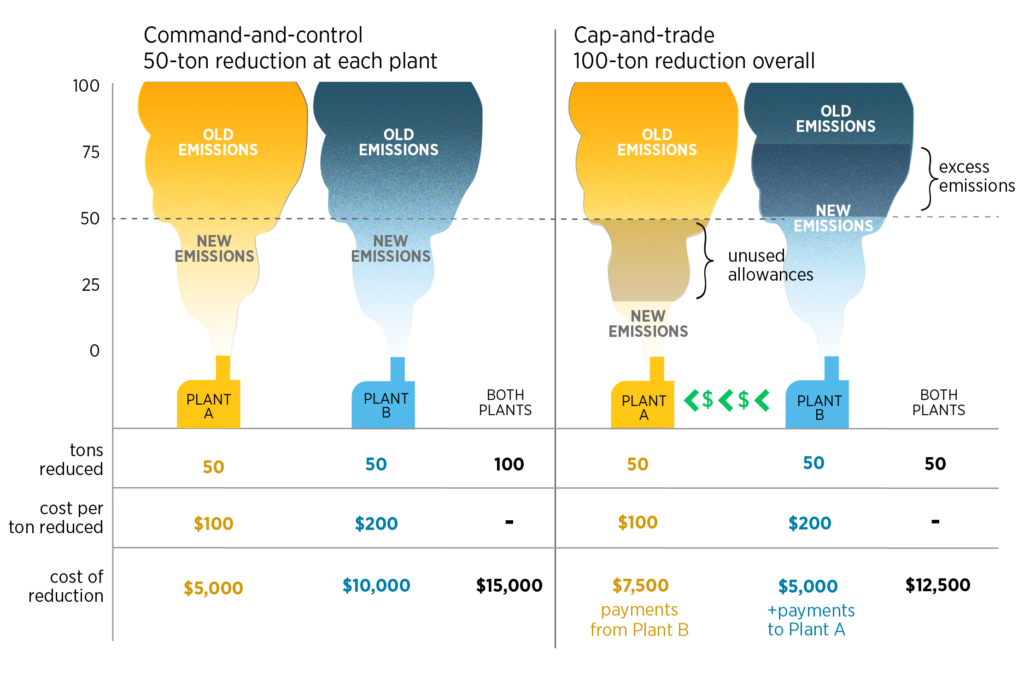

The parties to the Paris Agreement were aware of the herculean challenge and the enormous cost of decarbonization during the lead-up to its negotiation. Consequently, they agreed upon co-operative market mechanisms to help mitigate costs and achieve the treaty’s goals more quickly — and with the incentive for innovation and greater environmental ambition that the market can deliver. Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and its rulebook, largely set out in the Glasgow Climate Pact,[15] are the result of those ongoing efforts. Article 6 is based on the classic economic principle that if the marginal cost of producing an outcome is lower for one entity than another, both can benefit from co-operating to achieve the same combined outcome at a lower cost for each. The economics can occur among industrial plants within a country or all emissions sources between countries. As Figure 1 illustrates, a market-based approach (in this case, a basic cap-and-trade system) can enable the same emissions reduction with lower marginal cost to the system. A comparison between the two scenarios shows how the same system-wide emissions reduction outcome is achieved at a lower cost to the whole system through a co-operative approach between Plants A and B.

Figure 1 Efficiency achieved by market-based cooperative approaches for emissions reduction in the plant level

The basic rule is that ITMOs authorized by a host country for use towards another country’s nationally determined contribution or for other international mitigation purchases must be recorded as a debit for the transferring country and a credit for the receiving country; no double counting or claiming. This means that the emissions reductions and/or removals associated with an ITMO originating in Canada and exported to another country are added to Canada’s international emissions balance sheet and subtracted from the other country’s. Conversely, the emissions reductions and/or removals associated with an ITMO originating abroad and imported to Canada are subtracted from Canada’s international emissions balance sheet and added to the other country’s ledger. As an example:

- If Canada sells to Japan 100,000 tonnes of GHG emissions removals from advanced energy technologies such as carbon capture and storage implemented in Canada, on its reports to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)[16] Canada must add 100,000 tonnes of emissions to its reports (i.e., not account for the 100,000 tonnes of emissions reductions that occurred in Canada) and Japan can subtract 100,000 tonnes from its overall reported emissions.

- If Canada buys from Ghana 100,000 tonnes of GHG emissions reductions and removals from improved forest management in Ghana, on Canada’s reports to the UNFCCC[17] it must report 100,000 tonnes less emissions from the Ghana ITMOs (subtract 100,000 tonnes from its overall reported emissions), and Ghana must add 100,000 emissions to the negative emissions that would otherwise be attributable to its forest sinks.

International emissions trading and carbon pricing systems have been used and work well in the EU, U.S., Alberta, Quebec, Ontario and many other jurisdictions. To date, 73 jurisdictions around the world have carbon pricing systems in place covering 11.66 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents or 23 percent of global emissions.[18]

Generally, emissions trading systems provide flexibility to the regulated entities, allow for more ambitious targets and pollution reduction activities, lower costs when compared to traditional forms of emissions limits, protect human health and the environment, provide economic incentives for innovation and low- or no-emission technology, ensure accountability through enforced market rules, and bring the power of the market to incent unregulated entities to invest capital in the related markets.[19]

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement has the potential to deliver all these benefits but, to date, only a few countries have made use of this critical tool.

Recent economic modelling shows that international co-operation through Article 6 could significantly reduce the costs of the energy and economic transition required by the Paris Agreement relative to countries going about the same transition independently. The International Emissions Trading Association (IETA), together with researchers from the University of Maryland Center for Global Sustainability (CGS-UMD) and the World Bank-led Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, found in 2019 that there are significant cost savings for countries participating in Article 6 when compared to domestic-only regulation.[20] The study found that:

- Implementing Paris targets co-operatively through carbon markets, rather than trying to meet targets on a single-country basis, could save signatories an estimated US$250 billion per year by 2030.

- Moreover, if countries invest those cost savings in additional climate action, then Article 6 could facilitate additional GHG mitigation of approximately five gigatonnes of CO2 equivalents per year by 2030 (or the equivalent of about seven times Canada’s annual emissions).[21] Subsequent IETA and CGS-UMD research reinforces this point, concluding that all participating countries could increase ambition (their committed GHG emissions reductions) without incurring any greater cost than would have been incurred if they implemented their targets alone.[22] The market value of financial flows between countries could exceed US$1 trillion per year in 2050 and reduce mitigation costs by US$21 trillion between 2020 and 2050, driven by a sharp rise in global carbon prices over time.[23]

- IETA and CGS-UMD also found that, even where not every country co-operates through an international Article 6 carbon market, the benefits from cost savings always remain for those countries that do co-operate.[24] Countries that use the Article 6 mechanisms to co-operatively meet their Paris goals always benefit, whether they are a buyer or a seller, even though the modelled co-operative carbon price is sensitive to departures of key seller or buyer countries. The formation of “carbon clubs” — co-operative approaches involving a few, but not all, signatories to the Paris Agreement — still results in a lower modelled co-operative carbon price when compared with single-country domestic regulation, but the level of cost savings is higher in carbon clubs with greater diversity of marginal emissions mitigation costs. There are more limited gains from North-North or South-South co-operation.

It has been seven years since Article 6 was drafted and two years since its integral rules were elaborated, yet Canada has yet to embrace this tool — one of the most promising in the global toolbox for enabling the efficient, affordable and rapid approach to energy transition and ambitious decarbonization. This paper makes the case for Canada to co-operate now with other trading nations — and take a leadership position — to breathe new life into the Paris Agreement’s critical yet often overlooked Article 6.

Chapter 2: The Article 6 Rules and Requirements: Facts and Myths

The Paris Agreement’s 2030 targets are now just six years away and the global stocktake at the 2023 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Dec. 2023, more commonly known as COP28, is likely to demonstrate that we are falling far short of country targets and the Paris goals. Channelling capital at the levels required to the most efficient, effective decarbonization and adaptation uses in the time available will require significant global collaboration. Article 6 was included in the Paris Agreement to provide a framework for international co-operation that uses the efficiency of markets to optimize net-zero investment and mitigates the costs of the requisite energy and economic transition. It can mobilize additional public and private finance and expedite emissions reductions in a country that authorizes bilateral co-operation and hosts a mitigation activity (such as clean cookstoves in Peru and Malawi; low-carbon, sustainable rice farming in Ghana; and the replacement of diesel vehicles with electric vehicles in Bangkok’s privately owned, public transport system). It also enables countries participating in Article 6 co-operative mechanisms to access a portfolio of international options to reduce or remove GHG emissions more rapidly, efficiently and effectively than in their home jurisdictions. This facilitates the flow of necessary capital to finance decarbonization projects and greater overall GHG emissions reductions/removals at lower overall cost to the countries involved.

However, there are often significant misperceptions about the detailed rules and requirements of Article 6, including errant assumptions about which activities and projects may garner international credits. This section provides a high-level summary of the two key Article 6 mechanisms and highlights the applicable rules and requirements of the Article 6 rulebook, consisting of the Paris Agreement, the Glasgow Climate Pact and additional decisions made under the Paris Agreement.

Article 6 creates two main mechanisms for international co-operation through carbon markets:

- Article 6.2. Under Article 6.2, countries may voluntarily agree to co-operate on meeting their Paris targets (called nationally determined contributions, or NDCs) and enter into bilateral or multilateral arrangements to exchange ITMOs (internationally transferred mitigation outcomes). That co-operation is required to:

(i) Be authorized by the countries;

(ii) Allow for higher ambition in the countries’ GHG mitigation and adaptation actions;

(iii) Promote sustainable development;

(iv) Ensure environmental integrity and transparency (including in governance); and

(v) Apply robust accounting to avoid double counting in accordance with the Paris Agreement.[25]

The Article 6.2 mechanism is most likely to be used by countries, or entities authorized by countries, to achieve compliance with their Paris NDCs or other international GHG compliance systems that are not covered by the Paris Agreement, such as the International Civil Aviation Organization’s Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). - Article 6.4. Article 6.4 provides for a centralized multilateral crediting mechanism governed by the Article 6.4 Supervisory Body, which, as the regulatory body, makes decisions about how verified Article 6.4 GHG reduction/removal credits (known as Article 6.4 emissions reductions or A6.4 ERs) from qualifying projects may be created, which approved standards and methodologies will qualify for creation, and the detailed Article 6.4 procedures and rules.[26] A global exchange for holding and transferring A6.4 ERs may be facilitated by the international registry that forms part of the Paris Agreement infrastructure and through the World Bank and Singapore-led meta registry called the Climate Action Data Trust. The Article 6.4 Supervisory Body is in the process of developing a project standard and validation and verification standards, as well as requirements for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 methodologies. When authorized A6.4 ERs[27] are traded internationally, they become ITMOs governed by Article 6.2. The first Article 6.4 credits are expected to be issued in late 2024 or 2025.

Each of the Article 6.2 and 6.4 mechanisms have their own set of detailed rules that govern what activity or projects qualify, the steps needed to create an ITMO or A6.4 ER, accounting, tracking and other requirements set out in the Paris Agreement, Glasgow Climate Pact and additional decisions made under the Paris Agreement forming the Article 6 rulebook. The Article 6 rulebook was substantially completed at COP26 in Glasgow and continues to be refined/modified at the annual negotiations of parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA).[28] The key decisions to date are briefly outlined with corresponding hyperlinks in the table below.

Table 1: The Article 6 Rulebook

| Relevant provision | Decision | Achieved at: |

| Article 6 | Paris Agreement | COP21 (Paris) |

| Articles 6 and 13 (Transparency) | Paragraph 77(d) of the annex to Decision 18/CMA.1: Modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement | COP24 (CMA 1) (Katowice) |

| Article 6.2 | Guidance on co-operative approaches referred to in Article 6, paragraph 2, of the Paris Agreement | COP26 (CMA 3) (Glasgow) |

| Matters relating to co-operative approaches referred to in Article 6, paragraph 2, of the Paris Agreement | COP27 (CMA 4) (Sharm el Sheik) | |

| Article 6.4 | Rules, modalities and procedures for the mechanism established by Article 6, paragraph 4, of the Paris Agreement | COP26 (CMA 3) (Glasgow) |

| Guidance on the mechanism established by Article 6, paragraph 4, of the Paris Agreement | COP27 (CMA 4) (Sharm el Sheik) |

It is important to note that these rules are obligatory, not discretionary. Given that reality, we set out three common myths and the corresponding facts resulting from the Article 6 rulebook, and particularly the rules governing transfers of ITMOs between countries.

Myth #1: Any lower-carbon activity or export, including exports of lower-carbon fuels or power, can qualify as an ITMO.

Fact: The rules on ITMO creation require, among other things, that the GHG reductions/removals are real, verified and additional, generated from mitigation from 2021 and after, and authorized by the host country for use towards another country’s nationally determined contribution target or for other international mitigation purposes like CORSIA, an international aviation carbon offset and reduction co-operative market. Regular business-as-usual activities and lower-carbon fuel exports do not automatically meet the “additionality” criteria. But they may, in limited circumstances, be designed as part of a more comprehensive and novel bilateral arrangement between countries to lower overall, long-term energy emissions intensity in the receiving country so long as the appropriate reporting, tracking and evidence is in place. This is currently the objective of the U.S. Energy Transition Accelerator,[29] although it appears the United States itself does not intend to create ITMOs from this initiative but will instead allow participating corporate philanthropies to do so.[30]

Myth #2: The use or sale of any ITMO is unrelated to a country’s status under the Paris Agreement or how the ITMO is used.

Fact: Both country parties to an ITMO transaction must be parties to the Paris Agreement and account for the ITMO transfer through “corresponding adjustments” to their report on GHG emissions under the Paris Agreement. The country that transfers the ITMO cannot count the emissions reduction and the country that uses the ITMO can (with corresponding positive and negative adjustments to their reported GHG inventories). If the ITMO is authorized for use toward a nationally determined contribution, that corresponding adjustment happens when the ITMO is first internationally transferred. If the ITMO is for another international mitigation purpose, that corresponding adjustment happens when the transferring country authorizes it to happen (on the host country’s choice of authorization, issuance or use of the ITMO). Further, the transfer may not be valid if one of the countries is not in compliance with its core Paris Agreement obligations.

Myth #3: All A6.4 ERs are ITMOs when sold internationally and are subject to the ITMO rules.

Fact: Only A6.4 ERs that are authorized for use by the host country towards a nationally determined contribution or for other international mitigation purposes may become ITMOs. A6.4 ERs that are not authorized for these purposes are called mitigation contribution emission reductions (MCERs) and are not subject to the “corresponding adjustments” to the country’s GHG emissions inventory. Both A6.4 ERs and MCERs are tracked through a “mechanism registry” specific to Article 6.4. MCERs may be used for results-based climate finance, domestic mitigation pricing schemes or domestic price-based measures, for the purpose of contributing to the reduction of emissions levels in the host party, and potentially other uses that are the subject of ongoing Article 6.4 negotiations.[31]

These myths and facts illustrate some of the complexity of Article 6. They provide examples of what Article 6 is, and what it is not. Article 6 is a complex rules-based mechanism that has great potential to assist Canada and other countries in meeting their energy needs and Paris Agreement obligations more effectively, and at lower overall cost.

Article 6 is not a licence to pollute. Emissions reductions under Article 6 must ensure a net reduction in overall global emissions, rather than simply offsetting emissions released in one country with savings in another. Those emissions reductions and removals must be real, independently verified and additional; double counting is strictly disallowed. Article 6 is not, as is sometimes asserted in Canada, a panacea.

There is no doubt that other approaches are required to mitigate GHG emissions, foster adaptation to climate change and build economic and energy system resilience in Canada. Nonetheless, Canada should not overlook the cost efficiencies and global energy-transition benefits that Article 6 can provide domestically and abroad, particularly given Canada’s leading expertise in energy, decarbonization and low-emission innovation.

While there are many rules and requirements that must be followed in the Paris Article 6 rulebook, they are navigable, and a number of countries have successfully developed early approaches and entered into Article 6 transactions. Chapter 3 examines what leading countries have done under Article 6.

Chapter 3: Current Article 6 Approaches and Transactions

The additional clarity that COP27 provided on Article 6.2 has encouraged some countries to begin moving forward with bilateral agreements and policy frameworks. These agreements are still in their earlier stages, but trends can be discerned.[32] Each bilateral agreement provides a framework for future financing of initiatives and corresponding emissions adjustments, with one country acting as the financing (or buying) party and one country acting as the host (or selling) party. For example, Switzerland has entered into a bilateral agreement with Malawi to finance and purchase ITMOs from the installation of cookstoves (in lieu of open-fire cooking) in Malawi.

The 65 bilateral agreements reached since 2021 involve six different buyers in 42 host countries. The countries that have acted as a buyer are: Japan (number of bilateral agreements entered into: 28), Singapore (13); Switzerland (13), South Korea (6), Sweden (3), and Australia (2). Altogether, they are involved in a reported 136 pilot projects (or specific financed emission-reduction initiatives).[33] As can be seen, Asia has taken the lead while Canada has not yet made it to the starting line:

- To date, 113 of the pilot projects belong to Japan’s Joint Crediting Mechanism, a program established to facilitate bilateral arrangements between Japan and countries where Japan’s low-carbon products and technologies are exported, and the remaining 23 involve Switzerland as the buying/financing party. The remaining buyers that have entered into bilateral agreements — Australia, Singapore, South Korea and Sweden — have yet to report any specific projects;

- Three-quarters of the projects are in Asia, 13 percent in Africa, and six percent in the Americas;

- Thailand (25 projects, one of which is with Switzerland and the rest with Japan), Indonesia (32 projects with Japan), Ghana (nine projects with Switzerland), and Vietnam (18 projects with Japan) are among the early-mover host countries;

- The three most common categories for pilot projects are industry energy efficiency (47), solar (41) and service energy efficiency (14). Other categories of projects (in descending order of frequency) are energy distribution, transport, household energy efficiency, methane avoidance, landfill gas, supply-side energy efficiency, biomass energy, hydro, hydrofluorocarbons, agriculture and afforestation; and

- Three pilot projects already have authorization statements, which provide the formal recognition of the transfer of mitigation outcomes. These are Switzerland-Ghana (November 2022), Switzerland-Thailand (February 2023) and Switzerland-Vanuatu (June 2023).

To date, three of the projects have been the subject of authorizations and a total of 1.723 million tonnes of ITMOs have been transferred between buyers and sellers.

Japan’s Joint Crediting Mechanism

Japan is a long-standing leader in matters relating to Article 6 and efforts to finance emissions reductions abroad more generally. It reinforced its leadership at COP27 with its launch of the Article 6 Implementation Partnership,[34] which aims to promote capacity building by sharing best practices and know-how in support of the development of Article 6.2. The partnership currently counts approximately 70 countries, including Canada, as members.[35]

Even before Paris, Japan established the Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) as a program to facilitate the transfer of Japanese low-carbon technologies and infrastructure through investment by Japanese entities to developing countries for the purpose of reducing emissions. The JCM operates on the foundation of bilateral agreements, which Japan enters into with host countries. These host countries then submit their proposed project to a joint committee, composed of representatives from both Japan and the host country.[36] JCM’s typical model sees the Japanese government subsidizing up to half of initial investment costs and claiming an equivalent proportion of JCM (reduction) credits.[37]

As of August 2023, Japan had signed bilateral agreements with 27 countries under the JCM framework[38] and pledged to have project agreements with 30 countries in place — representing 100 million tonnes of CO2 reductions and removals — by 2025.[39] While these are mostly with smaller developing economies, in March Japan and India announced their intention to enter into a memorandum of understanding as a preliminary negotiating step towards a formal JCM partnership.[40]

Japan is also exploring ways to increase the involvement of the private sector in JCM, and commentators expect private companies will have more flexibility to enter into project arrangements and improved opportunity to acquire an increased proportion of JCM credits for various voluntary reduction purposes.[41]

Switzerland

Switzerland has a nationally determined contribution target of a 50 percent reduction of its 1990 GHG emissions by 2030. It anticipates achieving this objective in part by financing climate protection projects abroad, pursuant to Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement.[42] To date, Switzerland has entered into bilateral agreements with Ghana, Peru, Senegal, Georgia, Vanuatu, Dominica, Thailand, Ukraine, Malawi, Morocco, Uruguay and Chile.

Switzerland’s agreement with Peru in 2020 constituted the first Article 6 arrangement and serves as a general global precedent. This initial project will support the use of energy-efficient cook-stoves in Peru[43] and results in the transfer of ITMOs under Article 6.2. Switzerland has authorized the Swiss Foundation for Climate Protection and Carbon Offset (KliK), a private entity, to acquire ITMOs on behalf of Swiss motor fuel importers, who are required to offset GHG emissions under Swiss law.[44]

An agreement with Ghana has resulted in the first completed authorization under the Article 6 framework.[45] The project in Ghana will help train domestic rice farmers in sustainable agricultural practices, which will help reduce methane emissions.[46]

The world’s second authorized project was through a February 2023 bilateral agreement with Thailand. It authorized a program to introduce electric vehicles, replacing diesel vehicles, in privately operated public transport in the greater Bangkok Metropolitan Region.[47] KliK will purchase the resulting ITMOs, consistent with its role under Switzerland’s other existing bilateral agreements.[48]

KliK also has a major project underway in Malawi[49] — an initiative that aims to eliminate cooking over open fires and through the distribution of 10,000 biogas digesters to the country’s dairy farmers, turning cow manure into biogas.[50] The resulting methane emissions reductions are to be transferred to KliK.[51]

These projects are not mere purchases of lower-carbon commodities, but are sophisticated two-way arrangements that confer benefits on both parties.

U.S. Energy Transition Accelerator

The United States has also announced its intent to enter the sphere of carbon credits through the U.S. Energy Transition Accelerator (ETA) markets initiative. The ETA is the product of a partnership between the U.S. State Department, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Bezos Earth Fund that aims to catalyze private capital for the clean-energy transition.[52] The ETA anticipates the development of a “high-quality carbon credit framed by robust guardrails to channel much-needed private sector investment to phase out fossil fuels and accelerate renewable energy.” Participating jurisdictions would have the option to issue marketable carbon credits with respect to verified GHG reduction, which companies would then be eligible to purchase, generating the financing necessary to fund energy transition initiatives.[53] Early expectations are that the ETA will operate through 2030, possibly extending to 2035.[54]

Other countries are quickly moving into the emerging Article 6 space. Australia, Singapore, South Korea and Sweden have each entered into bilateral agreements with a range of host countries, but they have yet to report any resulting pilot projects or authorize any ITMO transactions. New Zealand has also indicated it may pursue Article 6 actions, with a priority on partnerships with countries in the Asia-Pacific region.[55] New Zealand and Chile have announced their intention to explore the possibility of an ITMO agreement,[56] and further details of New Zealand’s plans may become available before the end of 2023, when it is expected to release an ITMO strategy paper.[57]

In another part of the world, Africa Carbon Markets Initiative (ACMI) is being developed and is expected to generate 300 million carbon credits annually by 2030 and 1.5 billion by 2050. The initiative aims to generate $6 billion in revenue and support 30 million jobs by 2030 and over $120 billion in revenue and over 110 million jobs by 2050.

There are signs of early success. Recent efforts to sell ACMI credits at Africa’s first climate summit resulted in a pledge of $450 million from the United Arab Emirates and $200 million from Climate Asset Management.[58]

Chapter 4: Canadian Energy Leadership and a Path Forward on Article 6

Canada has made demonstrable and, in many cases, world-leading progress in decarbonizing its energy sector. While it continues to face challenges in decreasing the absolute GHG emissions of an oil and gas sector in which production growth over the last two decades has more than offset intensity gains,[59] several Canadian energy decarbonization strategies and outcomes are among the best in the world. In this chapter, we highlight five such areas that may be particularly conducive to Canada’s participation in Article 6 and provide potential pathways for rapid implementation.

1. Methane

Methane is a very potent GHG. It has a global warming potential of 25, which means that every tonne of methane reductions constitutes the equivalent of 25 tonnes of CO2 reductions. Canada is a world leader in the detection and control of methane. We are a charter member of the Global Methane Pledge to reduce methane emissions by 30 percent below 2020 levels by 2030, and the first country in the world to commit to reducing methane emissions from oil and gas by 75 percent of 2012 levels by 2030. Considerable progress is being made in achieving these reductions through comprehensive regulatory strategies, many of which involve technology measures to reduce methane flaring and venting, as well as emissions trading. Alberta is actively regulating methane emissions from conventional oil and gas in a bid to decrease them by 45 percent from 2014 levels by 2025. By 2021, and in large part thanks to the province’s long-standing compliance carbon market, Alberta had already achieved a 44 percent reduction.[60] New and enhanced technologies have been developed that reduce methane emissions through electrification, fuel switching and efficiency improvements with both conventional and unconventional oil. Innovative pilot projects are underway in the oil sands to reutilize methane and displace some natural gas in the extraction process.

Canada has developed sufficient expertise in reduced methane venting and flaring, and has allocated over $20 million to help other countries address their opportunities. It has allocated $2 million a year, with support from the Global Methane Initiative, to assist methane mitigation projects in developing countries such as Mexico and Colombia.[61] The end result is that we help achieve their Paris commitments by deploying our considerable technical expertise, just as was intended by Article 6.[62]

More than oil and gas

Methane opportunities go well beyond oil and gas. There is enormous potential, for instance, to reduce methane in the agricultural sector. The recently launched Agricultural Methane Challenge promotes incentives and pilot projects for dairy and cattle farmers, such as one that introduces feed additives into the diets of cattle and other ruminants that reduce their methane emissions.[63] From new adaptive agriculture management practices to de-risking new technologies, the Canadian agriculture sector is pioneering environmental market innovations with the potential to help other nations in their goals and in the overall reduction of global emissions through Article 6.[64] Similar prospects exist in waste management and other sectors.

Canada’s (and Alberta’s) drive to become a world leader in methane reductions is spawning a cluster of domestic cleantech and agtech companies, many of which have been helped in their development and growth by government investments. For example, Quebec-based GHGSat is a global leader in satellite methane detection. Canada has invested $20 million and Alberta has invested $3.75 million[65] to expand its fleet of high-tech satellites and provide methane data to the International Methane Emissions Observatory.[66] Canada is also a member of the Net-Zero Producers Forum, a platform for oil-and-gas-producing countries to collaborate on achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Canada is, for example, working collaboratively with Qatar to explore methane reduction possibilities from its oil and gas sector.[67]

Virtually all these Canadian cleantech initiatives and investments from 2021 onward could qualify for valid and efficient Article 6 arrangements. A portion of the resulting GHG reductions could form ITMOs that would count toward Canada’s Paris Agreement targets. This, in turn, may reasonably increase our national GHG reduction ambition without placing additional costs on the Canadian economy. The pathway is fairly straightforward and could be implemented in short order. This would also flag an early affirmation of Article 6’s value to Canada and the world through measures that are inarguably additional.

As such, Canada should explore:

- Negotiating bilateral Article 6.2 agreements with host countries as a pre-condition to any methane initiative Canada either (a) funds with the money currently allocated under the Global Methane Initiative or (b) supports through the Net-Zero Producers Forum (Qatar);

- Agreeing on a Paris-aligned allocation of GHG reduction (ITMO) benefits from international methane projects that result in fair and equitable sharing of the ITMOs from Canada’s funding and world-leading expertise; and

- Investing in ongoing methane monitoring and reporting using technologies such as GHGSat’s methane detection satellite technology.

2. Electrification

Between 2000 and 2021, Canada’s total electricity emissions fell by 60 percent[68] and about 83 percent of our national electricity generation now is non-emitting.[69] This electricity decarbonization performance is among the best in the world,[70] placing us in the ranks of the three lowest emitting members of the G20.[71] Moreover, Canada is ranked eighth in the world for installed wind capacity and 22nd in the world for installed solar capacity — and we haven’t even touched offshore wind yet.[72]

These are very significant markers and have been achieved while maintaining a reliable and diverse electricity generation supply mix from hydro, nuclear, biomass, biogas, natural gas,[73] renewables and various forms of cogeneration. Canada continues to implement an aggressive phaseout of coal-fired electricity generation, with two provinces already off coal. While going up elsewhere in the world, the quantity of coal consumed for electricity in Canada dropped 58 percent between 2010 and 2021.[74] Just five percent of the supply still comes from coal.[75]

Each of coal-to-natural gas conversion, renewables, non-emitting generation, battery storage, and post-combustion carbon capture and storage play a critical role in our successful and ongoing electricity sector decarbonization. So, too, do the electricity system operators, who have developed innovative dispatch and other market rules to facilitate the coal phaseout.

The role of Canadian natural gas

To be clear, natural gas has had, and will continue to have, a key role in country-wide, multi-faceted electricity and industrial sector decarbonization in many countries around the world. That said, liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports from Canada, despite the relatively low carbon intensity of our gas, will be challenged to meet the criteria of additionality and “leakage avoidance” required to substantiate Article 6 credits unless they are part of more complex and comprehensive arrangements. So, determining precisely how we incorporate LNG technologies and exports into broader and multi-faceted clean electricity and industrial transition strategies that assist trading partners who are still reliant on coal generation is vital if these products are to conform with the Glasgow Article 6 rulebook.

It is certainly feasible for Canada to incorporate coal-to-gas transition for electricity generation into a broader envelope of energy transition initiatives for countries in the upper reaches of power and heating sector emissions. Rather than standing alone, the related LNG exports will have to be part of a comprehensive, country-wide strategy that also includes renewables, nuclear, energy storage, post-combustion carbon capture and storage, electricity transmission, energy efficiency and conservation. Such a bundled approach can be conducive to the rapid, least-cost, highest-reliability, additional, and lowest-emission leakage outcomes that Article 6 necessitates.

A comprehensive energy transition strategy that uses Canadian expertise and low-carbon resources could be deployed to assist countries such as the U.S., Japan, Mexico, Chile, Germany, China, India, Nigeria and South Africa to decarbonize in a more efficient and effective manner.[76],[77] It is also in line with what the U.S. is trying to achieve through its Energy Transition Accelerator, by including the private sector. The federal government can negotiate bilateral agreements for “jurisdictional energy transition” to deploy a Canadian “energy transition SWAT team” in these countries with an agreed formula for sharing the resulting Article 6 credits. In this manner, Canada would facilitate the export of lower-carbon Canadian energy technologies, resources and expertise and obtain the benefit of a portion of the Article 6 credits realized in the country where the exports are deployed. In short, Canada has been very successful at electricity sector decarbonization, largely thanks to getting off coal, and continues to explore 2035 net-zero goals for the sector through additional regulatory measures.[78] The expertise we have acquired in the process puts Canada in an enviable position to assist other countries with their significant electricity sector decarbonization challenges. This may, if implemented properly, qualify for multi-faceted Article 6 arrangements, with energy and energy service export benefits as well as a portion of the resulting GHG reductions forming ITMOs that are transferred to Canada in exchange for project activities and investments. The pathway is more complex than for methane as it is likely to initially require jurisdiction-wide evidence of permanent decreases in the host country’s emissions intensity and, ultimately, in its absolute emissions.

To achieve this outcome, Canada should explore:

- Establishing an international energy transition SWAT Team with talented and entrepreneurial members from each of the renewables, natural gas, nuclear, hydro, carbon capture and storage, energy storage and efficiency sectors, as well as experienced leaders from the Ontario and Alberta electricity system operators experienced at getting off coal;

- Working with the U.S. Energy Transition Accelerator to use and build upon the jurisdictional energy transition quantification methodologies that it has developed and is anticipated to release at COP28;

- Working with Canadian oil and gas exporters and renewable energy developers operating internationally to help identify jurisdictions that are most conducive to significant electricity transitions and related bilateral arrangements with Canada and the Electricity Transition SWAT Team;

- Entering into bilateral or multilateral Article 6.2 agreements with the host country/countries for energy services (and potentially products) arranged through the SWAT Team;

- Agreeing on a Paris-aligned allocation of GHG reduction (ITMO) benefits that result in fair and equitable sharing of the ITMOs generated from Canada’s and the SWAT Team’s expertise, services and, potentially, products; and

- Facilitating ongoing measurement, monitoring and reporting of the electricity sector emissions from the host country/countries for a durable period of time.

3. Carbon Removal

Canada is at the forefront of the development of innovative technologies for producing and using energy. Many Canadian cleantech companies are supported by Canadian or provincial government investments and deploy emissions-reducing or removing technologies in countries around the globe. Yet neither Canada nor these companies are harvesting the benefits of Article 6.

More than half of Canada’s 2,427 cleantech companies work in energy, renewables, energy efficiency and smart grid technology. More than 170 of them provide proven and affordable clean-technology services with global impact. They include Canadian-funded, groundbreaking negative-emission technology companies like Squamish-based Carbon Engineering.[79] Its technology removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and permanently stores it.[80] Meanwhile, Gatineau-based Planetary Technologies’ ocean alkalinity enhancement process removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and safely reduces local ocean acidity.[81] Dartmouth-based CarbonCure is deploying Canadian-funded carbon capture, usage and storage technology to strengthen concrete while capturing emissions.[82] These companies and countless others should be in a position to benefit from Article 6. Some, instead, are left to resort to the far more limited voluntary carbon market to harness GHG reduction/removal benefits from their Canadian-funded technology. We can do better.

These CO2 removal processes seem likely to satisfy the requirements of Article 6.2. They are well-suited to generate ITMOs, which could be apportioned through co-operative bilateral arrangements between Canada and any country in which they are deployed.

Similarly, the ongoing deployment of Canadian low- or zero-emissions innovation can be found in areas such as grid-scale electricity storage, carbon capture and storage, and electric and alternative fuel vehicles. To date, none have benefitted from Article 6. Most are resorting to European and voluntary carbon markets in an effort to monetize the benefits of their GHG removals. A more purposeful Canadian approach to Article 6 can provide market-based incentives that create a national advantage without taxpayers footing the bill.

Japan, through its Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM), has established a reasonable precedent to mobilize Article 6 pathways for cleantech innovation deployed internationally.

To achieve this outcome, Canada should explore:

- Facilitating access to the benefits and resulting ITMOs from Article 6.2 for all the GHG emissions reducing/removing technologies that Canadian governments help fund, and providing an export development “push” to the innovating companies;

- Providing Canadian cleantech innovation companies with “one-window” access to Article 6 through a mechanism like Japan’s JCM (see Chapter 3);

- Building on Japan’s Article 6 leadership and the close trading relationship between the two countries by opening discussions about Canada’s participation in the bilateral arrangements Japan is pioneering;

- Entering into additional bilateral or multilateral Article 6.2 agreements with host countries where Canadian technologies are deployed;

- Agreeing on a Paris-aligned allocation of GHG reduction (ITMO) benefits that result in fair and equitable sharing of the ITMOs from Canada’s investment in the cleantech projects and the countries where they are deployed; and

- Facilitating ongoing measurement, monitoring and reporting from the projects.

Attention should also be paid to hydrogen. Canada is one of the top producers in the world today, with an estimated three megatonnes produced per year.[83] Although probably not quite there yet, it is up-and-coming for Article 6 treatment, with investment occurring in Canada and a great deal of trade interest from Europe and Asia. While much of this hydrogen production is currently carbon intensive, the federal and provincial governments are investing and incentivizing low-carbon outcomes through vehicles such as the Clean Resource Innovation Network, the Alberta Industrial Heartland, the Quebec Green Hydrogen and Bioenergy Strategy,[84] the Ontario Hydrogen Innovation Fund,[85] and the B.C. Hydrogen Strategy and Hydrogen Office.[86]

Canada is advancing the transformation of various industrial sectors and leveraging its low-emissions infrastructure (zero-emission power generation; carbon capture, usage and storage; gas storage and handling; transportation infrastructure) to facilitate industrial-scale hydrogen production and use. Our expertise is in both the production of hydrogen and its expanded use in chemical and fertilizer production, oil and gas refining, and heavy transportation, among others.

Canada is also helping to fund various industrial processes that may ultimately turn to hydrogen. Hamilton-based ArcelorMittal Dofasco is converting its blast furnaces to electric arc furnaces, using high-grade direct reduced iron ore from Labrador, with the intention of an eventual move to hydrogen as its power source.[87] In Alberta, Dow is developing a project that will convert off-gases into hydrogen as a clean fuel to be used in the ethylene production process, and carbon dioxide will be captured on site to be transported and stored.[88]

Conclusion

Article 6 presents considerable unrealized opportunity for Canada to contribute to the global Paris Agreement goals and achieve its own GHG targets more rapidly, with greater ambition and at lower cost. Simple estimates based on Canada’s share of global emissions, as well as the analyses from the International Emissions Trading Association and the University of Maryland Center for Global Sustainability,[89] indicate that Canada could save significant costs and achieve greater emissions reductions by including Article 6 among its climate change policy tools.[90] It also presents a major opportunity to export and expand the market for Canadian resources and expertise, as well as low- and zero-emissions technologies.

Many countries have much higher energy-related emissions and emissions intensity, but do not have the same access to natural or financial capital that Canada does. Article 6 provides a “win-win” opportunity for Canada and partner countries to achieve material transitions of their energy sectors. It allows for: (i) host countries to gain access to much-needed Canadian capital, knowledge, resources and technology to attain proven energy transition outcomes and benefit from a portion of the Article 6 emissions reductions achieved; and (ii) Canada to benefit from a portion of the Article 6 emissions reductions achieved, lower costs of meeting its nationally determined contribution, and the potential for even greater GHG reductions, while creating new and expanded export markets for Canadian low- or no-emission innovations and resources.

Japan has seized these potential benefits for the better part of the last decade; Canada would be wise to rapidly mobilize its Article 6 process and mechanisms to avoid being displaced or usurped in key energy transition markets.

While the benefits may prove greatest from Canadian bilateral agreements with developing countries, Article 6 arrangements can certainly extend to developed trading partners as well. Canada and the U.S. have a connected, integrated electricity transmission system, and it is noteworthy that U.S. absolute electricity sector emissions are currently nearly 100 times (absolute emissions)[91] and 3.5 times (emissions intensity) higher than Canada’s figures. There is considerable opportunity for further cross-border collaboration using Article 6 through the existing U.S.-Canada Memorandum of Understanding on energy co-operation.[92]

There do not appear to be any economic, structural, trade or policy barriers that prevent Canada from actively engaging in Article 6 and reaping its many potential benefits. And virtually no other country in the world has the same mix of natural and human resources, knowledge and financial capital, and proven innovation to achieve energy sector decarbonization results.

It will, however, require a resource that is currently in limited supply in the federation: federal-provincial co-operation on climate policy. The potential benefits to Canadian companies, the Canadian economy and Canadians in general from the use of Article 6 are too great to exclude this critical tool from our climate change and innovation toolbox.

Canada should neither shy away from nor somehow be embarrassed by the significant and successful outcomes it can realize on the energy transition at home and abroad. We urge governments and industry to seize the above-highlighted opportunities by aggressively moving to implement Article 6 and manifest clear areas of Canadian energy transition leadership around the world.

Sponsors

Endnotes

- Speer, S., Henderson, K., and Feenan, K. (October 2021). CLIMATETIVENESS: What it Takes for Canada to Thrive in a Net Zero Exporting World. https://ppforum.ca/publications/climatetiveness-what-it-take-for-canada-to-thrive-in-a-net-zero-exporting-world/?sf_data=all&sf_paged=3. Public Policy Forum. ↑

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2023). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. p. 42. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_FullVolume.pdf. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 10-11. Note: the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement are to limit “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” ↑

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (September 2023). Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5°C Goal in Reach (2023 Update), p. 32. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/d8a5171b-4d00-4366-812b-679feab341c6/NetZeroRoadmap_AGlobalPathwaytoKeepthe1.5CGoalinReach-2023Update.pdf. ↑

- Ibid., p. 22. ↑

- See IEA, “Net-Zero (2023 Update),” where the IEA estimates that global temperatures are projected to rise by 2.4°C and IPCC, “Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report,” p.11, where the IPCC estimates the current trajectory to result in temperatures rising by 3.2°C. ↑

- UNFCCC Secretariat. (Sept. 8, 2023). Technical dialogue of the first global stocktake. Synthesis report by the co-facilitators on the technical dialogue, para. 10. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sb2023_09_adv.pdf. UNFCCC. ↑

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada. (2023). Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development’s Opening Statement to the news conference. https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/osm_20230420_e_44255.html. Government of Canada. ↑

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2023). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. p. 46. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_FullVolume.pdf ↑

- Ibid., p. 5. ↑

- Krishnan, M., et al. (Jan. 25, 2022). The economic transformation: What would change in the net-zero transition. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/the-economic-transformation-what-would-change-in-the-net-zero-transition. McKinsey & Company. The sectors studied by McKinsey include mobility, fossil fuels, biofuels, hydrogen, heat, carbon capture (not including storage), buildings, industry (steel and cement), agriculture and forestry but do not include spending to support adjustments such as spending to reskill and redeploy workers, compensate for stranded assets, or account for the loss of value pools in specific parts of the economy. ↑

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (September 2023). Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5°C Goal in Reach (2023 Update), p. 15. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/d8a5171b-4d00-4366-812b-679feab341c6/NetZeroRoadmap_AGlobalPathwaytoKeepthe1.5CGoalinReach-2023Update.pdf. ↑

- Royal Bank of Canada. (Oct. 20, 2021). The $2 Trillion Transition: Canada’s Road to Net Zero. https://thoughtleadership.rbc.com/the-2-trillion-transition/. ↑

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2023). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. p. 25. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_FullVolume.pdf. ↑

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (Dec. 13, 2021). The Glasgow Climate Pact – Key Outcomes from COP26. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-glasgow-climate-pact-key-outcomes-from-cop26. ↑

- Canada’s Annual Report under Article 6, its annual National Inventory Report and its Biennial Transparency Report. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- The World Bank. (n.d.). Carbon Pricing Dashboard. https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org. ↑

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (Nov. 16, 2023). Why Do Emissions Trading Programs Work? https://www.epa.gov/emissions-trading-resources/why-do-emissions-trading-programs-work. ↑

- Edmonds, J., et al. (September 2019). The Economic Potential of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and Implementation Challenges.https://www.ieta.org/wpcontent/uploads/2023/09/IETAA6_CLPCReport_2019.pdf. International Emissions Trading Association / Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition. ↑

- Canada’s total GHG emissions in 2021 were 670 megatonnes (0.67 gigatonnes) CO2e in 2021, the most recent year for which data are available. Environment and Climate Change Canada. (2023). National Inventory Report 1990-2021: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/greenhouse-gas-emissions/inventory.html. ↑

- Edmonds, J., et al. (May 2023). Modelling the Economics of Article 6: A Capstone Report. https://www.ieta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/IETAA6_CapstoneReport_2023.pdf. International Emissions Trading Association / Center for Global Sustainability at the University of Maryland. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Paris Agreement Articles 6.1, 6.2 and 6.3. ↑

- The transition of clean development mechanism (CDM) activities to the Article 6.4 mechanism is a significant issue that is the subject of ongoing negotiations and the supervisory body has adopted a standard and procedure for the transition. The role of CDM credits (known as certified emission reductions) in the Article 6.4 mechanism is beyond the scope of this report. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/a64-sb006-a01.pdf and https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/a64-sb006-a02.pdf. ↑

- Unauthorized A6.4 ERs are known as mitigation contribution emission reductions (MCERs) and their treatment is currently the subject of negotiation at the annual Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP). ↑

- Technically, the COP is the annual Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC, and the CMA is the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the parties to the Paris Agreement made under the UNFCCC. ↑

- U.S. Department of State. (Nov. 9, 2022). U.S. Government and Foundations Announce New Public-Private Effort to Unlock Finance to Accelerate the Energy Transition. https://www.state.gov/u-s-government-and-foundations-announce-new-public-private-effort-to-unlock-finance-to-accelerate-the-energy-transition-2/; Bezos Earth Fund. (Sept. 19, 2023). Energy Transition Accelerator and World Bank Announce Strategic Collaboration to Scale Up Clean Energy Finance. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/energy-transition-accelerator-and-world-bank-announce-strategic-collaboration-to-scale-up-clean-energy-finance-301932633.html#:~:text=ETA%20%E2%80%93%20a%20partnership%20of%20the,innovative%20jurisdictional%2Dscale%20carbon%20crediting. PR Newswire. ↑

- See Chapter 3 below, U.S. Energy Transition Accelerator. ↑

- UNFCCC. (Mar. 17, 2023). CMA 2022 Report. Guidance on the mechanism established by Article 6, paragraph 4, of the Paris Agreement. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2022_10a02_adv.pdf#page=33. ↑

- UN Environment Programme. (Nov. 2, 2023). Article 6 Pipeline. https://unepccc.org/article-6-pipeline/. Copenhagen Climate Centre. To date there have been 61 BAs for cooperation signed pursuant to Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement. UNEP. “Article 6 Pipeline”, (2 September 2023), online: <https://unepccc.org/article-6-pipeline/>. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ministry of the Environment. (Nov. 17, 2022). Launch of the “Paris Agreement Article 6 Implementation Partnership”: Towards High Integrity Carbon Markets. https://www.env.go.jp/en/press/press_00741.html#:~:text=About%20the%20. Government of Japan. ↑

- Ministry of the Environment. (n.d.). Paris Agreement Article 6 Implementation Partnership (About). https://a6partnership.org/#countries. Government of Japan. ↑

- Greiner, T., et al. (2019). Moving towards next generation carbon markets: Observations from Article 6 pilots, p. 54. https://www.climatefinanceinnovators.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Moving-toward-next-generation-carbon-markets.pdf. Climate Focus and Perspectives. ↑

- Kuo, C. (Apr. 6, 2023). Japan announces $114-mln budget for latest JCM project finance push. https://carbon-pulse.com/198600/. Carbon Pulse. ↑

- Global Environment Centre Foundation. (August 2023). Introduction of the Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) & Financing Programme for JCM Model Projects, p. 1. http://carbon-markets.env.go.jp/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/JCM2023Aug_En_Web.pdf. ↑

- Kuo, C. (Aug. 17, 2023). Japan to co-fund four new JCM projects. https://carbon-pulse.com/217106/#:~:text=Japan%27s%20environment%20ministry%20has%20identified%20four%20projects%20under%20the%20Joint,required%20to%20read%20this%20content. Carbon Pulse. ↑

- Reklev, S. (Mar. 31, 2023). Japan, India announce intention to forge carbon trading partnership under the JCM. https://carbon-pulse.com/197895/. Carbon Pulse. ↑

- Kuo, C. (Mar. 28, 2023). Japan rejigs JCM to boost private-sector interest. https://carbon-pulse.com/197285/. Carbon Pulse. ↑

- 43 Federal Office for the Environment. (May 8, 2023). Bilateral climate agreements. https://www.bafu.admin.ch/bafu/en/home/topics/climate/info-specialists/climate–international-affairs/staatsvertraege-umsetzung-klimauebereinkommen-von-paris-artikel6.html. Government of Switzerland. ↑

- Tuki Wasi. (Mar. 14, 2022). ITMO in Peru: A Pioneer Agreement. https://tukiwasi.org/en/itmo-in-peru-a-pioneer-agreement/. ↑

- KliK Foundation. (n.d.). Foundation programme. https://www.international.klik.ch/en/programme?opened=1937. ↑

- United Nations Development Programme. (Nov. 12, 2022). Ghana authorizes transfer of mitigation outcomes to Switzerland. https://www.undp.org/ghana/press-releases/ghana-authorizes-transfer-mitigation-outcomes-switzerland; United Nations Development Programme. (Nov. 12, 2022). Ghana, Vanuatu, and Switzerland launch world’s first projects under new carbon market mechanism set out in Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement. https://www.undp.org/geneva/press-releases/ghana-vanuatu-and-switzerland-launch-worlds-first-projects-under-new-carbon-market-mechanism-set-out-article-62-paris-agreement. ↑

- United Nations Ghana. (Nov. 14, 2022). Ghana authorizes transfer of mitigation outcomes to Switzerland. https://ghana.un.org/en/207341-ghana-authorizes-transfer-mitigation-outcomes-switzerland. ↑

- KliK Foundation. (Feb. 28, 2023). ’Bangkok E-Bus Programme’ authorised by Switzerland and Thailandunder Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. https://www.southpole.com/news/bangkok-ebus-programme-authorised-by-switzerland-and-thailand. ↑

- Janssens, V. (June 19, 2023). Thailand and Switzerland walking the talk: example of cooperation on e-buses in Bangkok under the Article 6. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjWgo_NzZaBAxUEJH0KHWOUD9E4ChAWegQIBhAB&url=https%3A%2F%2Fentregis.set.or.th%2Fapi%2Fpublic%2Ffile-store%2F59412da0-a4d8-4817-91a8-436d44a9747c&usg=AOvVaw0nuSDGbj0tNhLqKPnIXjap&opi=89978449. KliK Foundation. ↑

- KliK Foundation. Malawi: About Us. https://malawi.klik.ch/about-us. ↑

- KliK Foundation. Malawi: Malawi Dairy Biogas. https://malawi.klik.ch/activities/Malawi-Dairy-Biogas ↑

- KliK Foundation. Malawi: Cookstove and Sustainable Biomass Programme. https://malawi.klik.ch/activities/Cookstove-and-Sustainable-Biomass. ↑

- The Rockefeller Foundation. (Nov. 19, 2022). Bezos Earth Fund, The Rockefeller Foundation, and U.S. State Department Announce Support at COP27 for Design of New Energy Transition Accelerator. https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/news/bezos-earth-fund-the-rockefeller-foundation-and-u-s-state-department-announce-support-at-cop27-for-design-of-new-energy-transition-accelerator/. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- U.S. Department of State. (Nov. 9, 2022). U.S. Government and Foundations Announce New Public-Private Effort to Unlock Finance to Accelerate the Energy Transition. https://www.state.gov/u-s-government-and-foundations-announce-new-public-private-effort-to-unlock-finance-to-accelerate-the-energy-transition-2/. U.S. Government. ↑

- New Zealand Ministry for the Environment. (June 29, 2023). Government climate-change work programme. https://environment.govt.nz/what-government-is-doing/areas-of-work/climate-change/about-new-zealands-climate-change-programme/; Tilly, M. (Aug. 29, 2023). NZ needs to come clean on its ITMO strategy, analyst says. https://carbon-pulse.com/218682/. Carbon Pulse. ↑

- Lithgow, M. (July 21, 2022). Chile, New Zealand to consider Article 6 ITMO cooperation under new approach. https://carbon-pulse.com/167078/. Carbon Pulse. ↑

- Tilly, M. (Aug. 30, 2023). New Zealand to imminently release ITMO strategy paper, minister says. https://carbon-pulse.com/218964/. Carbon Pulse. ↑

- Miriri, D. (Sept. 5, 2023). Hundreds of millions of dollars pledged for African carbon credits at climate summit. https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/africa-climate-summit-opens-with-focus-financing-continental-unity-2023-09-04/. Reuters. ↑

- Canada is the world’s 4th largest oil producer and 5th largest natural gas producer — and the oil and gas sector makes up nine percent of Canada’s GDP and 28 percent of its GHG emissions. GHG emissions from oil and gas production increased 23 percent between 2000 and 2021, largely from increased oil sands production. Emissions per barrel of oil equivalent are actually falling, particularly in situ extraction. See Natural Resources Canada. (2023). Energy Fact Book 2023-2024, p. 128. https://energy-information.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/energy-factbook-2023-2024.pdf. Government of Canada. ↑

- Government of Alberta. (Apr. 6, 2023). 2021 Methane emissions management from the upstream oil and gas sector in Alberta, p. 12. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/7e41d270-075f-498c-9b3d-7b822c930760/resource/f4fe807e-0763-43e7-9c96-f107b3fbf8ab/download/epa-methane-emissions-management-upstream-oil-and-gas-sector-2021.pdf. ↑

- Government of Canada. (n.d.). Faster and Further: Canada’s Methane Strategy. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/climate-plan/reducing-methane-emissions/faster-further-strategy.html. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. (Nov. 14, 2023). Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada launches new Agricultural Methane Reduction Challenge. https://www.canada.ca/en/agriculture-agri-food/news/2023/11/agriculture-and-agri-food-canada-launches-new-agricultural-methane-reduction-challenge.html. Government of Canada. ↑

- Government of Alberta. (n.d.). Climate smart agriculture – Livestock systems. https://www.alberta.ca/climate-smart-agriculture-livestock-systems. ↑

- Emissions Reduction Alberta. (n.d.). Satellite-aircraft hybrid detection and quantification of methane emissions. https://www.eralberta.ca/projects/details/satellite-aircraft-hybrid-detection-and-quantification-of-methane-emissions/. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Natural Resources Canada. (2023). Energy Fact Book 2023-2024, p. 68. https://energy-information.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/energy-factbook-2023-2024.pdf. Government of Canada. ↑

- Ibid., p.62. ↑

- Based on data from https://ember-climate.org/countries-and-regions/regions/g20/, Canada’s electricity sector decrease in emissions between 2000 and 2021 appears to be the best in the world, but data not independently confirmed. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Canadian Renewable Energy Association. (n.d.). By the Numbers. https://renewablesassociation.ca/by-the-numbers/. ↑

- A combination of federal and provincial policies and regulations, including the draft Clean Electricity Regulations, are intended to result in a phaseout of coal-fired generation in Canada. ↑

- Natural Resources Canada. (2023). Energy Fact Book 2023-2024, p. 137. https://energy-information.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/energy-factbook-2023-2024.pdf. Government of Canada. ↑

- Ibid., p. 68. ↑

- International Energy Agency. (n.d.). Countries and regions. https://www.iea.org/countries. ↑

- Tiseo, I. (June 16, 2023). Global electricity generation emissions 2022, by country. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1300487/global-power-sector-emissions-by-country/. Statista. ↑

- Canada has released draft Clean Electricity Regulations, which closed for comment on Nov. 5, 2023. ↑

- Carbon Engineering was recently sold to a U.S. company, Oxy 1PointFive, but remains in Canada. ↑

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. (n.d.). Innovations to reduce methane emissions. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/global-methane-initiative/innovations-reduce-methane-emissions.html. Government of Canada. Carbon Engineering’s direct air capture technology continuously captures CO2 from atmospheric air and delivers it as a gas for use or storage, bringing together four major pieces of equipment that each have industrial precedent. On Sept. 12, 2023, 1PointFive, a carbon capture, utilization and sequestration company, announced that Amazon agreed to purchase 250,000 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide removal credits over 10 years. Carbon Engineering technology has also supported transactions with Airbus and All Nippon Airways. ↑

- Planetary’s ocean alkalinity process removes carbon from the atmosphere and safely reduces local ocean acidity. Planetary is working with Nova Scotia Power, Inc. and entities in the UK. ↑

- Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency. (n.d.). CarbonCure Technologies. https://www.canada.ca/en/atlantic-canada-opportunities/campaigns/impacts/carboncure.html. ↑

- Natural Resources Canada. (2023). Energy Fact Book 2023-2024, p. 97. https://energy-information.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/energy-factbook-2023-2024.pdf. Government of Canada. ↑

- Government of Quebec. (n.d.). Quebec Green Hydrogen and Bioenergy Strategy. https://www.quebec.ca/en/government/policies-orientations/strategy-green-hydrogen-bioenergy. ↑

- Government of Ontario. (n.d.). Ontario’s Low-Carbon Hydrogen Strategy. https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontarios-low-carbon-hydrogen-strategy. ↑

- Government of British Columbia. (2019). B.C. Hydrogen Strategy. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/farming-natural-resources-and-industry/electricity-alternative-energy/electricity/bc-hydro-review/bc_hydrogen_strategy_final.pdf#page=5. ↑

- Public Policy Forum. (Apr. 20, 2023). The Strength of Green Steel. https://ppforum.ca/publications/the-strength-of-green-steel/. ↑

- Dow Chemical Company. (Apr. 25, 2023). Dow selects Linde as clean hydrogen and nitrogen partner for its proposed net-zero carbon emissions ethylene and derivatives complex in Canada. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/dow-selects-linde-as-clean-hydrogen-and-nitrogen-partner-for-its-proposed-net-zero-carbon-emissions-ethylene-and-derivatives-complex-in-canada-301805966.html. PR Newswire. ↑

- IETA. (n.d.). Modelling the Economic Benefits of Article 6. https://www.ieta.org/initiatives/modelling-the-economic-benefits-of-article-6/. ↑

- The IETA-MD study indicates that, on a global basis, Article 6 could save signatories to the Paris Agreement an estimated US$250 billion per year by 2030. Moreover, if countries invest those cost savings in additional climate action, then Article 6 could facilitate additional GHG mitigation of approximately five gigatonnes of CO2 equivalents per year by 2030. By a very rough and conservative estimate, Canada produced 1.5 percent of global emissions (https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions.html), and 1.5 percent of these benefits is equal to US$3.75 billion in annual savings by 2030 and .075 Gt (or 750 Mt) of CO2e per year by 2030 — a number greater than Canada’s total emissions inventory. ↑

- U.S. electricity sector emissions are 1.539 million metric tonnes https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=77&t=11#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20emissions%20of%20carbon,of%20about%204%2C964%20(MMmt).; Canadian electricity sector emissions are 51.7 million metric tonnes https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/greenhouse-gas-emissions.html#electricity; U.S. electricity sector emissions intensity is 0.86 pounds/kWh (0.39 kg/kWh) https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=74&t=11; and Canada’s electricity sector emissions intensity is 0.11 kg/kWh https://www.cer-rec.gc.ca/en/data-analysis/energy-markets/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles-canada.html. ↑

- Natural Resources Canada. (June 24, 2021). Canada Strengthens Energy Partnership With the United States. https://www.canada.ca/en/natural-resources-canada/news/2021/06/canada-strengthens-energy-partnership-with-the-united-states.html. Government of Canada. ↑