A New North Star

Canadian Competitiveness in an Intangibles EconomyRise of the intangibles

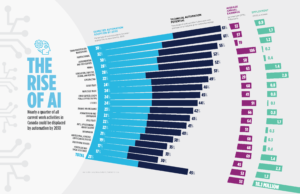

When New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady played in his first Super Bowl in 2002, there was no iTunes store, no Facebook, no Instagram, no Airbnb, no Gmail and no Skype. Today the companies who own these intangible assets are worth more than $4 trillion. The rise of the intangibles economy will have sweeping policy implications that will become clearer over time. Nobody knows for sure where this is heading.

Our overriding objective in this paper is to help catalyze a bi-partisan policy discussion about a new “north star” for Canada’s economic competitiveness and the types of policy reforms needed to start us on this path. As part of this process, we set out a series of policy recommendations that cover the classic drivers of competitiveness such as taxation and regulation and drivers for the intangibles economy such as data governance, intellectual property retention, and the race for talent. But as important as these prescriptions are, the main takeaway for policymakers and the Canadian public is that the rise of the intangibles economy requires that we test old assumptions and are open to new thinking. Canada’s economy cannot afford complacency in this new economic era.

We need a new competitiveness consensus

In the world of policy and politics, short-termism and complacency are difficult to resist. They trump partisanship. They trump best intentions. Pressure mounts on any government or political party to respond to immediate issues and keep an eye fixed on the four-year election cycle. Both of us observed these demands in our respective positions as economic advisers to national governments.

The problem is that reactive governance is inconsistent with the mix of long-term policies required to promote broad economic participation and growth. For a competitiveness agenda to maintain and raise Canadians’ quality of life, it demands discipline, focus and a vision that extends beyond the election cycle. It thus requires a multi-partisan commitment. A change in government may naturally result in new preferences and priorities, but it should not cause us to lose collective sight of the common bases of competitiveness, productivity and jobs, and the greater opportunities and outcomes they produce for successive generations.

What we can do:

- Encourage policy-makers to focus on Canada’s economic long-term competitiveness, avoid the pitfalls of short-termism and construct a renewed policy consensus of the sort that has existed around free trade and other issues for a quarter century;

- Call for a broad-based and inclusive vision for competitiveness that avoids exclusion and elitism; and

- Draw attention to the extent to which the rise of the intangibles economy will require changing conventional thinking about economic competitiveness.

The paper’s analysis and recommendations have not been reached through a process of horse-trading. As former senior advisers to different governments, we have placed a priority on practicality and political survivability. Others will no doubt have their own thoughts on what a long-term competitiveness agenda will require. We welcome that. This paper is not intended as the last word on what it will take for Canada to achieve a bold and doable consensus, but as an early salvo in an essential and serious national dialogue about how Canada will secure lasting competitive advantage in an era of massive economic change.

Watch Asselin and Speer on BNN Bloomberg TV

Competitiveness panel: Canada Growth Summit 2019