The Data Talks: How Statistics Canada Measured a Pandemic

Series | Public Service Innovation and Leadership During COVID-19Ziad Shadid was stumped. Canada’s economy has had its ups and downs, crashes, failures and recessions, but how do you measure the business impact of a country that simply stopped working and intentionally shut down its economy to halt the spread of COVID-19?

Shahid is Statistics Canada’s Director General of Agriculture, Energy, Environment, and Special Business Projects, which put him at the centre of finding ways to track how businesses were faring in a once-in-a-century pandemic that was upending Canadians, their behaviour and the economy.

The statistics agency was flooded with a rush of frantic requests and queries from business, governments and researchers in the days after Prime Minister Justin Trudeau ordered businesses to close and told Canadians to stay home.

This will be the study of historians for years to come. Never had Canada, and much of the world, shut down the economy; there was no playbook on measuring its impact to help steer governments and business into a recovery.

Statistics Canada has plenty of tools for measuring the economy, whether employment went up or down or size of the GDP increased or decreased, but it didn’t have tools to measure impact on business when an economy is deliberately put to sleep, said Shadid.

“They were very foundational questions, but at the time, it was very hard for anyone to really understand the impact on business of shutting down an entire economy,” said Shadid.

“We have limited tools to measure anything like this because we’re going through an unprecedented situation for which we have no basis for comparison. This is not like the economy is in a bit of a tailspin or the economy is failing. There is nothing to compare to because we’ve never before shut down the economy on purpose.”

Overnight, Canada’s 102-year-old statistical agency was bombarded with questions for which it had no answers nor ready tools on how to find them quickly. Yet, in a matter of days, Statistics Canada launched two new collection tools to help fill the data gaps on the economic and social impact of COVID-19 on Canadians – web panels and crowdsourcing.

Within four weeks, Shadid led a team to figure out what both business and policymakers needed to know immediately, and released the Canadian Survey on Business Conditions, the first in a series to help tell the story of how Canadians are living in a pandemic.

“We need to see what’s happening on the ground,” said Patrick Gill, the Senior Director of Tax and Financial Policy at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, which partnered with StatCan on the survey.

“We know locking down the economy at a macro level that the GDP is going to tank but what’s happening on Main Street? That’s where this survey comes in. And we had to move quickly.”

Meanwhile, Karen Mihorean, Statistics Canada’s Director General for Social Data Insights, Integration and Innovation, was getting ready to test the use of web panels to gather information about Canadians on a slew of topics.

Web panel surveys were designed to be quick, short, online – a drastic turnaround from the traditional 45-minute surveys done in person or by telephone that Canadians increasingly find burdensome.

Her team had lined up about 7,200 Canadians to test the survey when the country plunged into lockdown and Statistics Canada — along with the rest of the federal public service — was sent home to work remotely.

She pivoted. A pilot survey about online shopping behaviour quickly turned into a series of basic questions about how the pandemic is affecting Canadians and their health. The Canadian Perspectives Survey Series was born and was in its sixth wave of data collection by the fall.

These new tools proved critical in helping StatCan fill data gaps around racial, social and economic inequities that many argued were hampering efforts to manage the pandemic. Such inequities were painfully revealed by COVID-19, especially among visible minorities, immigrants, seniors and Indigenous people.

Along with an insatiable demand for data, StatCan had to respond to a sea change in public attitudes about racial and social injustice as the world erupted in Black Lives Matter protests over the death of George Floyd, an African-American who died in police custody in May.

“The pandemic clearly shone a light on the pre-existing inequities in Canadian society that existed before COVID but were exposed by the pandemic,” said Assistant Chief Statistician Lynn Barr-Telford, who leads the agency’s social, health and labour statistics field.

She said StatCan will be gathering more of the “disaggregated and granular data” to help policy makers better “understand the diverse experiences of diverse groups of Canadian.”

StatCan tackled the issue of race-based data on multiple fronts. It added more questions about ethnicity on its crowdsourcing surveys and launched a separate survey on discrimination to get at the inequities people faced — whether by race, ethnicity, age or as members of the LBGTQ community. In July, it revised its 70-year-old Canadian Labour Force Survey with additional questions about race and ethnicity.

“Telling the labor market story of COVID using our traditional means, and our traditional narrative just wouldn’t have cut it,” said Barr-Telford.

“We really needed to adapt the way we think about the labour market, the way we use our existing measures, supplement them and add other types of information so that we can better track the impact. In a nutshell, this was important for Statistics Canada because it reflects our modernization journey but also key for Canada to have more timely and granular information in a pandemic.”

As a result, its methodologists, analysts and subject matter experts looked for new data by using existing datasets in different ways. They integrated and linked data from new surveys, its regular stable of surveys and administrative data to give policymakers data they never had before.

‘We have limited tools to measure anything like this because we’re going through an unprecedented situation for which we have no basis for comparison. This is not like the economy is in a bit of a tailspin or the economy is failing. There is nothing to compare to because we’ve never before shut down the economy on purpose.’ – Ziad Shadid, Statistics Canada

Innovations went beyond new collection tools

The pandemic also handed Statistics Canada the opportunity to showcase the efforts of its ambitious modernization in the telling of Canadians real-time story living with the coronavirus.

For many line departments, COVID-19 triggered the kind of innovation that the government has unsuccessfully tried to ignite for years with various reforms. Up against it, bureaucrats suddenly became creative and took risks. They developed new programs, apps, software, revamped processes or systems on the fly.

But Statistics Canada, an independent agency, was already in the throes of innovation, knee-deep in an ambitious modernization plan launched three years ago to restore the agency’s relevance in a world exploding with new information and data.

Since then, the agency had been working on finding new ways to deliver information faster and cheaper without sacrificing data quality, and COVID-19 became the trial run that will arguably set a new standard for statistical agencies around the world.

In the first six months of the pandemic, StatCan was able to launch, collect, analyse and release data from six web panels and eight crowdsourcing initiatives — warp speed compared to the months or years for a single survey.

The traditional survey that can take a year or more — from start-to-finish and cost upwards of $1 million — gave way in recent years to “Rapid Stats” which are done in three to four months at half the cost. Web panels knocked months off that and delivered results within three weeks. The only big cost is the questionnaire at about $150,000.

A new method of collecting data isn’t as simple as writing a survey and emailing a link for people to fill in. Experts from every branch in the agency’s various fields are pulled in to write questions, design and develop, code, test, validate, distribute, collect and analyse responses.

Leila Boussaïd, the Director of Operations and Integration for Census, Regional Services and Operations whose branch developed 30 COVID-related surveys on the fly, said innovations went far beyond collecting data. She said the internal processes to develop, build, collect data and the way teams worked and collaborated also had to be revamped — work that began under the modernization plan but went into overdrive to get COVID-19 surveys out the door quickly.

It’s a feat that StatCan managers still marvel about. Thousands of employees sent home with no equipment, spotty network connections, working nights and weekends and many shuffled to jobs they normally didn’t do. No more door-knocking for surveys; hundreds of interviewers had to be set up to work at home.

It meant cutting corners, skipping steps. Changing and even throwing out processes, which can be difficult for punctilious statisticians who managed to get surveys out the door in record time. It’s also raised the question of how many of those processes were needed in the first place.

And that put a big onus on management who had to manage risks while encouraging staff to take them. It was up to managers to assume responsibility and “own” the risks they were asking their teams to take, said Larry MacNabb, Director of the Centre for Social Data Integration and Development.

“If there was too much humming-and-hawing and hand-wringing, I would just take ownership of the decision and that allowed people to move forward,” he said.

“I have told my bosses the big reason we could do this so quickly was because of people. They dedicated themselves to make this and did whatever it took to make it happen. We solved this because of our people, not our tools. “

The whole effort accelerated the agency’s modernization plan by up to two years. As one statistician said, “we are doing today what we planned to be trying a year from now.”

Modernization and COVID-19: The rehearsal for the live show

Many statisticians, methodologists and analysts interviewed said it’s difficult to separate the modernization of Statistics Canada over the past several years from its COVID-19 response. You couldn’t have had one without the other.

They argue Chief Statistician Anil Arora’s push to modernize laid the groundwork for a rapid COVID-19 response that would have been unimaginable a few years ago in an agency that avoided risk and prided itself on precision. That response, in turn, accelerated the modernization agenda and collapsed several years of culture change into a few months.

Statistics Canada had the hallmarks of an agency that had to catch up with technology or risk irrelevance when it launched a massive modernization plan three years ago.

The StatCan of today was born out of Dominion Bureau of Statistics in 1918 with a mandate to collect administrative and survey data to help Canadians better understand their country. From punch cards to the internet, the agency grew into an internationally recognized statistical agency that conducts more than 380 surveys on 32 different subjects and takes a census of Canada’s population and agriculture every five years.

For most of those years, Statistics Canada used the sample survey methodology developed in the 1940s. The methods StatCan used to get Canadians to respond and do those surveys evolved over the years, from using the mail and pen-and-paper to personal interviews. The use of telephone for interviews was the biggest disruption in survey-taking until the internet came along.

Today, StatCan Canada employs a mixed bag of methods to reach all generations of Canadians – mail, telephone, personal interviews, online surveys and more recently email and text messages.

With changes in technology, came big data. The world is swimming in information and many questioned whether Statistics Canada was losing its relevance in feeding timely data to policymakers. This at a time when many argue reliable, accurate and trustworthy data has never been more important than in a world awash in disinformation and fake news.

The agency realized it no longer had a monopoly on data. What’s more, in a world flooded with data-spewing devices and fake news, it had to solidify its long-held position as the trusted source of reliable and quality data. Chief Statistician Anil Arora said Statistics Canada had to change or “risk being left behind, or worse, becoming obsolete.”

StatCan built its international reputation on tools that no longer work. Response rates are declining, and Canadians and governments want data fast and from various sources so they can make decisions in real time.

Modernization was the push was to think outside the box, take risks and find new ways to collect and analyse data quickly.

“For us, the defining features of relevance is the pertinence of the information we’re collecting, as well as the timeliness of the information we’re collecting and the trust factor in the information collected,” said Barr-Telford.

StatCan’s main data-gathering fields or divisions – economic and social statistics – have had special teams and projects rethinking how the agency works. They were tasked to improve the timeliness of data by finding new sources of information, new methods, processes and collaborating more closely with partners. Statisticians today are gathering information using administrative data, web scraping, open data and microdata linkages to bolster, supplement or replace its traditional surveys — all while protecting Canadians’ confidentiality and private information.

One of MacNabb’s jobs is to modernize the agency’s social statistics; make better use of administrative data, turn around surveys faster, reduce costs and reduce the burden on survey respondents. He called Arora an “extroverted leader” who has pushed the agency out of its “comfort zone” and into more interaction with government to better understand what departments want and need.

“We were still worrying about dotting our I’s and crossing our T’s and making sure things were perfect before we moved to the next step, but he pushed us well out of our comfort zone and we were working on planning and how to make these things happen. What COVID did was force us to take calculated risks.

“That’s key to the whole thing. If we had run into this pandemic, even five years ago, I’m not sure what the response would have been. We would have been scrambling to figure out how to do it.”

Changing the game: Speed and collaboration

With the country in lockdown, there was little interest in Statistics Canada’s March release of Gross Domestic Product. What happened in the previous pre-coronavirus quarter seemed completely irrelevant for an economy put on ice.

In fact, none of the agency’s existing surveys captured the up-to-date information needed as “the sands of the economic landscape shifted so drastically on a weekly basis,” said Patrick Gill of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.

“We need to provide data on what is going on this week, right now and how businesses are doing this week and the past week, said Alessandro Alasia, Assistant Director of the Centre for Special Business Projects.

“Nobody was interested in our regular statistical programs that were providing information about the past quarter or the past six months. That was the key challenge.”

Businesses wanted to find out about layoffs, trade, exports, expenses, stimulus support and how long firms can last without cash coming in. And what will the world be like when they reopen? They clamoured for information now to come up with strategies to survive and keep businesses going.

Some businesses, however, were doing fine. Others boomed, particularly if they could adapt quickly or shift their employees and operations to run remotely. Repair shops or services that relied on people coming in felt the pinch, as did restaurants unless they introduced takeout or outdoor dining.

Gill said the “game changer” came when StatCan and the Chamber teamed up to collaborate on the design and launch of the Canadian Survey on Business Conditions within days of the economic shutdown to collect “real time” data on the pandemic’s impact.

Shadid said the big problem was data gaps. Existing surveys measuring the normal ups and downs of an economy, not one thrust into shutdown.

StatCan and Chamber officials met in the days after the lockdown and realized together they were going to have to come with up with new survey to fill those gaps so business could survive and ready for recovery. Policy-makers from the Privy Council Office and Innovation Science and Economic Development had many of the same questions so they could make decisions on what kinds of supports businesses needed to carry them through.

“Rather than getting a general idea of what people are looking for, and then developing a questionnaire, we work very much arm-in-arm in ensuring that the questionnaire addressed specific needs that industry and policymakers have,” said Shadid.

The first survey in April was all about liquidity and cash flow to get a handle on resiliency and how businesses were adapting. Questions flowed in from business, and governments of all levels, around how long they could go without revenues. Could they cover expenses; keep employees or let them go; switch to new services or products; shift to e-commerce; find new ways to reach customers?

A new survey that would take months wasn’t going to fly for thousands of shuttered businesses desperate for data to help them figure out how to survive. The decision was to crowdsource, using email to get people to answer an online survey.

StatCan had previously experimented with crowdsourcing, but it was still controversial among by-the-book statisticians. It’s unscientific and a dramatic departure from surveys built on probability or random sampling to ensure they have picked a group of people who represent the real-life population they are studying.

‘Instead of taking a long time to create its own survey, it moved faster by using crowdsource methodology to get it out and actually worked with the business community on designing the questions that matter most.’ – Patrick Gill, Canadian Chamber of Commerce

There’s no control on sample selection; anyone can sign up, and a crowdsource survey only reports on what the participants say. The responses can’t be generalized to the population. The upside: it is fast and can attract large numbers of people to respond.

And that fit perfectly with the government’s push for “speed over perfection” in shaping its COVID-19 response.

There was no time for the usual field testing of survey questions, especially in such an uncertain and rapidly changing environment, said Shadid. The pressing questions of one week were no longer relevant the next week when new ones emerged. In April, for example, business and government scrambled to figure out the impact of closures. By May, the panic shifted to how to re-open and if there were PPE supplies for employees returning to work.

“The crisis doesn’t have the same challenges and hurdles at every turn. Shutting down the economy was one thing and reopening was another,” said Shadid.

“The innovative part was finding a creative mechanism that works in broad collaboration with the right partners in a very short amount of time …. We launched a survey; got buy in so people complete it and give us quality data to help inform decision makers. All in a handful of weeks. That’s one third of the time that we normally take.”

The survey was the first step, the challenge was getting enough people to answer to make the responses meaningful and get pulse on what business was doing. The Chamber brought the “buy-in” among business and industry to answer the survey.

The Chamber has a network of 450 chamber of commerce and boards of trade across the country. Its reach, however, was broadened with the Chamber’s creation of Canadian Business Resilience Network, pulling in more than 100 of Canadians leading business and industry associations, for an all-out campaign to mitigate the pandemic’s impact and “build resilience against future shocks.”

“And to be very blunt, if I was a business owner, and the government just shut me down … the last thing on my mind is filling out a questionnaire,” said Shadid. But when it’s coming from the Chamber of Commerce, it gets more buy-in and traction, because it’s not the government asking for this data. It’s the Chamber telling business we need you to fill out these questionnaires to get the information we need to help you when we’re asking government for support programs.”

Business was anxious for the first survey to get out the door. It was promoted through thousands of members of the Business Resiliency Network to drum up participants, along with StatCan’s communications campaign. The survey attracted 12,500 responses.

The next survey in May took a more scientific approach so its findings could be broadly extrapolated to more businesses.

StatCan put together a random sample from its business register, a central repository it keeps on businesses operating in Canada.

The surveys not only asked questions never asked before, but also provided data at regional and local levels that wasn’t available in existing surveys.

But Gill argued the big breakthrough was getting a better breakdown on the diversity of businesses and how they are faring. With concerns that minority communities were hit harder by the pandemic, Statistics Canada worked closely with business network to get a handle on how minority-led businesses were coping; were they using government emergency supports and how they were situated for the future?

Those questions were front-and-centre in the second survey which asked business owners taking the survey to self-identify by race, ethnicity, gender and whether they are Indigenous or LGBTQ2.

Gill argued the surveys became “one of the most sought-after data sets” for policymakers and business leaders. Municipalities and provinces followed up with data and research requests to dig deeper in the pandemic’s impact on their local businesses, restaurants and manufacturers.

“This is the first time any StatCan product did this on business ownership and good for them because such important information was captured. The impact of this recession is being felt differently by different demographic groups than the last recession and the traditional forms of asking questions weren’t capturing that story,” said Gill.

But Gill said the survey showed that although diverse-owned businesses are disproportionately hit by the pandemic, they appear to be more agile, faster to adapt and innovate than average firms. They were quick to shift more into new production or services; go online, invest in new equipment, and adapt with research and development.

“With all the doom and gloom news that we’ve heard through the crisis, the data sets have really shown an innovation story coming through I haven’t seen this level of business innovation and adaptation in Canada in years. It’s huge,” said Gill.

There have been three business conditions surveys so far and the plan is to continue, as long as needed, with results released every quarter.

Shadid said the big challenge for future surveys is finding ways to engage minority communities to they answer questions in sufficient numbers for meaningful analysis.

A voluntary survey may not get enough responses from specific groups, such as Black or Asian business owners, to extrapolate their experiences. The groups can’t be selected because participants are drawn from the business register, which collects information by business type — such as restaurateur, manufacturing or hospitality — not race or ethnicity.

“Hats off to StatCan on reaching out,” said Gill. “Instead of taking a long time to create its own survey, it moved faster by using crowdsource methodology to get it out and actually worked with the business community on designing the questions that matter most.”

Measuring behaviour in a pandemic: Changes in health, labour and society

The coronavirus was already on the radar of StatCan’s social insights team as it watched the spread from China last January. They knew it was a matter of time before it reached Canada. Analysts were already examining what issues government could be confronting and what data StatCan had on hand that could be used to shed light on who faced the greatest risks.

That turned into a full-blown domestic crisis in mid-March when Canadians were sent home; offices, restaurants and borders closed; and those abroad were told to come home.

Mihorean’s branch, which is responsible for social data, innovation and integration, pulled together a working group of experts from the large social statistics portfolio – including Centre for Population Health Data, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics; Centre for Gender Diversity and Inclusion Statistics and Centre for Labour Market.

They quickly met, along with the departments and other stakeholders they serve, to figure out the issues and possible social data gaps that would have to be filled to help manage the pandemic. They prioritized data needed first and what could be collected later.

“It’s one thing to be able to watch real-time changes in the economy, but we don’t tend to have real-time data when it comes to social issues,” said Steve Trites, Director of the Centre for Social Data Insights and Innovation Division.

The questions were flying. Employment and Social Development Canada was hungry for real-time social and economic data while Health Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada gobbled up anything about Canadians’ behaviour.

Health officials, for example, had no idea whether Canadians were following their advice – are they washing their hands, using sanitizer, social distancing or wearing masks? Did behaviour and compliance vary in different parts of the country? All was key information, not only for targeting public health campaigns, but also for modeling the spread of the virus.

With modernization, the group had already been looking for new ways to collect social statistics, typically built on surveys given to groups of statistically represented Canadians. Traditional surveys take 30 to 45 minutes, given by interviewers on the phone or in-person at the respondents’ homes.

Those surveys were becoming an uphill battle. Getting and keeping respondents was high-maintenance work. People are busy, not as keen to fill out surveys; harder to reach by phone and seemed baffled that with all the information they already provide to government why some of that couldn’t be used.

Mihorean said Statistics Canada worked harder – spending more time and money – every year to get Canadians to fill out the surveys and maintain critical target response rates.

StatCan had introduced Rapid Stats – known within the agency circles as its “Jiffy Lube” or “Speedy” survey – which became the new gold standard for timeliness. They are cheaper and short, with 10 to 15 questions, and offered clients a 90-day turnaround. They’ve been used for a range of topics from opioid use and cannabis to childcare and the digital economy.

Web panels: A faster but scientific way

The next experiment was web or online panels. They are popular polling tools, using a sample of people who volunteer to take surveys via the internet. They can attract large numbers of respondents and churn out results much faster and cheaper than live telephone or hiring interviewers.

The downside for scientifically minded statisticians is that panel members are not randomly selected. They are usually volunteers who are recruited online and are not statistically representative of the larger population.

But Mihorean’s team had a plan for that. They recruited respondents from the pool of people StatCan had carefully selected as representative of the broader population for the Canadian Labour Force Survey.

The labour force survey is mandatory and reaches about 150,000 people – in 60,000 households. A new batch of people rotate in and out of the respondent pool every six months. StatCan asked 32,000 of those departing the survey if they would be volunteers for web panel every couple of months. A huge sigh of relief came when 7,200 of them agreed — a substantial and statistically representative pool to answer new surveys over the next few months.

The team was set to begin testing web panels with questions on online shopping when the country went into lockdown. It quickly changed course and launched the first web panel survey to gather insight on COVID-19.

There were six web panels during the first wave of the coronavirus with topics ranging from impact, types of social and economic activity, cybersecurity and substance use.

Crowdsourcing: Taking the pulse

At the same time, senior management was pressing for more “granular” information, finding ways to dig down into what people were doing and thinking by geography and sub-population; where they lived, their ethnicity, race, whether they were disabled, Indigenous or identified as LGBTQ.

For that, they turned to crowdsourcing.

With the help of its communications branch, it recruited people for the survey on its website and pumped similar messages on Twitter, Facebook, Linked In. It appealed to other departments which did the same through their social media channels.

And Canadians came in droves. After four weeks, 250,000 Canadians had answered the survey – and then half of them offered their email addresses and agreed to take part in others being planned for the summer.

“We were amazed by the response, and quite impressed. It wasn’t scientifically based but it gave us a really good pulse of how Canadians were behaving and what they were thinking in a very timely fashion,” said Mihorean.

MacNabb said the “stars were aligned” for the crowdsourcing initiative. The media latched on to it and Canadians, worried and locked down in their homes, gladly volunteered to talk about how COVID-19 was affecting their lives.

“The circumstances were so unprecedented that I think we have a captive audience, so to speak, wanting to say something and we were there wanting to hear what they had to say,” he said.

In the early days of the pandemic, Canadians were obsessed about the virus and worried about their health and falling ill. The numbers dropped as infections dropped and restaurants and businesses opened over the summer. Those health anxieties spiked again as infection surged in the fall with the second wave but so did economic worries.

“This is very fluid situation and there wasn’t mechanism for these types of indicators….so we needed to create an opportunity to capture this information,” said Trites.

For example, as stores and restaurants started to re-open, a big missing piece in planning the recovery was just how comfortable Canadians are about returning to these businesses. The question was asked in both the web panels and crowdsourced surveys and the information fed into modeling on how fast it would take the economy to recover.

Mihorean said analysts at the Centre for Insights and Innovation “kept their ears to the ground” to pick up these shifts in mood and behaviour as the pandemic progressed. That enabled them to assemble surveys “on a dime” as new issues came up from parenting to vaccines. (This team handles the front-end and back-end of the survey; coming up with the questions to ask and later analyzing the responses.)

They picked up, for example, the worry of post-secondary’s students when COVID-19 forced the closure of colleges and universities and courses were moved online, postponed or cancelled. Questions swirled around whether students were moving out of residences, the impact on summer jobs, paying for next year’s tuition and what if schools were closed in the fall.

StatCan experts quickly teamed up with its education networks in provinces and territories to help promote the survey at all universities and colleges, drawing more than 100,000 students taking the survey over two weeks in mid to late April.

Crowdsourcing was also used to probe Canadians’ mental health, personal safety, trust in government, families and discrimination during the pandemic.

To keep a check on crowdsourced results, the survey asks some of the same questions as those posed to the web panels so analysts can compare responses and determine if the findings are similar or wildly different.

Crowdsourcing is voluntary and participants skew among the well-educated, women and residents of Ontario and B.C. Mihorean said the data was “cleaned up” and adjusted to reduce bias using StatCan’s population benchmarks, such as age and gender. The data trends for both types of surveys proved strikingly similar, giving statisticians comfort when releasing crowdsourced data.

They used other surveys as benchmarks to track the changing behaviours found in the real-time surveys. By using the latest Canadian Community Health Survey on mental health, Statistics Canada tracked the deteriorating mental health of Canadians over the months of the pandemic, especially among young Canadians, women and recent immigrants.

StatCan tapped into disabled organizations to recruit participants for a crowdsourced survey on how those with disabilities were faring over the pandemic. It also worked with organizations like Children First and Vanier Institute of the Family to get surveys to families for questions on parenting in the pandemic.

In early days, they raced to use existing data to help the government develop models on risk and the pandemic’s spread, such as the Canadian Community Health Survey, which found 38 per cent of Canadians have underlying chronic conditions that could leave them vulnerable to the virus.

Measuring the measurement: More work to be done

Statistics Canada had previously tried crowdsourcing for several projects. The most high-profile was using crowdsourcing to get a handle on economic impact of legalizing marijuana by calculating its contribution to the GDP.

Statistics Canada had an idea of how many Canadians consume marijuana and how much, but it needed a better handle on how much they paid for it on the black market. It turned to users and asked them. The anonymous online responses were beyond expectations and StatCan was able to come up with a price.

François Brisebois, Director of Social Statistics Methods Division, said he and fellow methodologists had to “get in their heads” that crowdsourcing was not the gold standard they are used to, but has a place for “providing a pulse or signal” on how Canadians are feeling at the moment.

Equally as important, he said, is to ensure people using the responses know the limitations. It’s a reading, more like a finger testing the way the wind is blowing, than a definitive finding. Methodologists have even coined terminology so surveys and crowdsourcing can’t be confused. Surveys have respondents and estimations; crowdsourcing has participants and indicators.

“Methodologically, this was very different for a cup of tea for us,” said Brisebois.

“We had to make sure our users understood this is not typical. This is not official statistics that can be used for decision making. This is data we got quickly because we really need something and can’t wait months before getting an indication of what’s going on. This was an alternative thing to do.”

Overall, web panels have been a success, said Mihorean. They had a huge head-start because when the coronavirus hit because much of the up-front work had been done preparing for the pilot. The responses, however, were in line other data sources so the next step is to “expand and improve” their use and “make them more ‘robust,” said Mihorean.

She recommends more participants for future web panel and create a bigger pool of respondents. One way is to broaden recruitment from those rotating out of the labour force survey – who are already in big demand as would-be respondents for other surveys. She said they are looking at recruiting respondents from other scientific surveys, such as the Canadian Community Health Survey or the General Social Survey, for web panels.

The jury is still out on the future use of crowdsourcing. StatCan will also be developing directive and principles on the appropriate use of crowdsourced data, which will be closely watched by statistical agencies around the world.

“I don’t think crowdsourcing will ever go away . . . but the exact role that it will play in a national statistics office is something we need to figure out,” said Mihorean.

“There’s a place for crowdsourcing; we showed that through COVID. But to make real statistical inferences, you need something that’s more scientific. That’s why we want to further explore and build on the success of the web panel … This is where I think we really should be focusing our efforts and resources on developing the robustness of web panels.”

MacNabb said he would “think long and hard” before recommending a crowdsourced survey. Policy-makers love it because results are quick, but it only works with large volumes of responses. He argued StatCan struck it rich when Canadians thronged to surveys to give their views on the uncertain times of a pandemic. He questions whether that would have happened in normal times.

“We really have to think through when this is really appropriate to use.”

The story of the pandemic’s impact is still being written. Statisticians say it will change and shape a generation and they will be studying the social and economic impact for years to come.

Barr-Telford said the coronavirus drives home how integrated the pieces of our lives are. The invisible virus that threatened the world’s health, turned all parts of Canadians’ lives upside down – work, incomes, families, education – and often unequally. Surveys can simply zero in on topics. The StatCan of the future must look at these social and economic intersections and how they affect the quality of life in Canada.

“COVID crossed multiple domains of our lives but we need to understand whether different groups of Canadians felt the same impacts … And that intersection of who you are and the different domains of life is really key to capture. COVID-19 accelerated Statistic Canada’s capacity to tell those integrated stories,” she said.

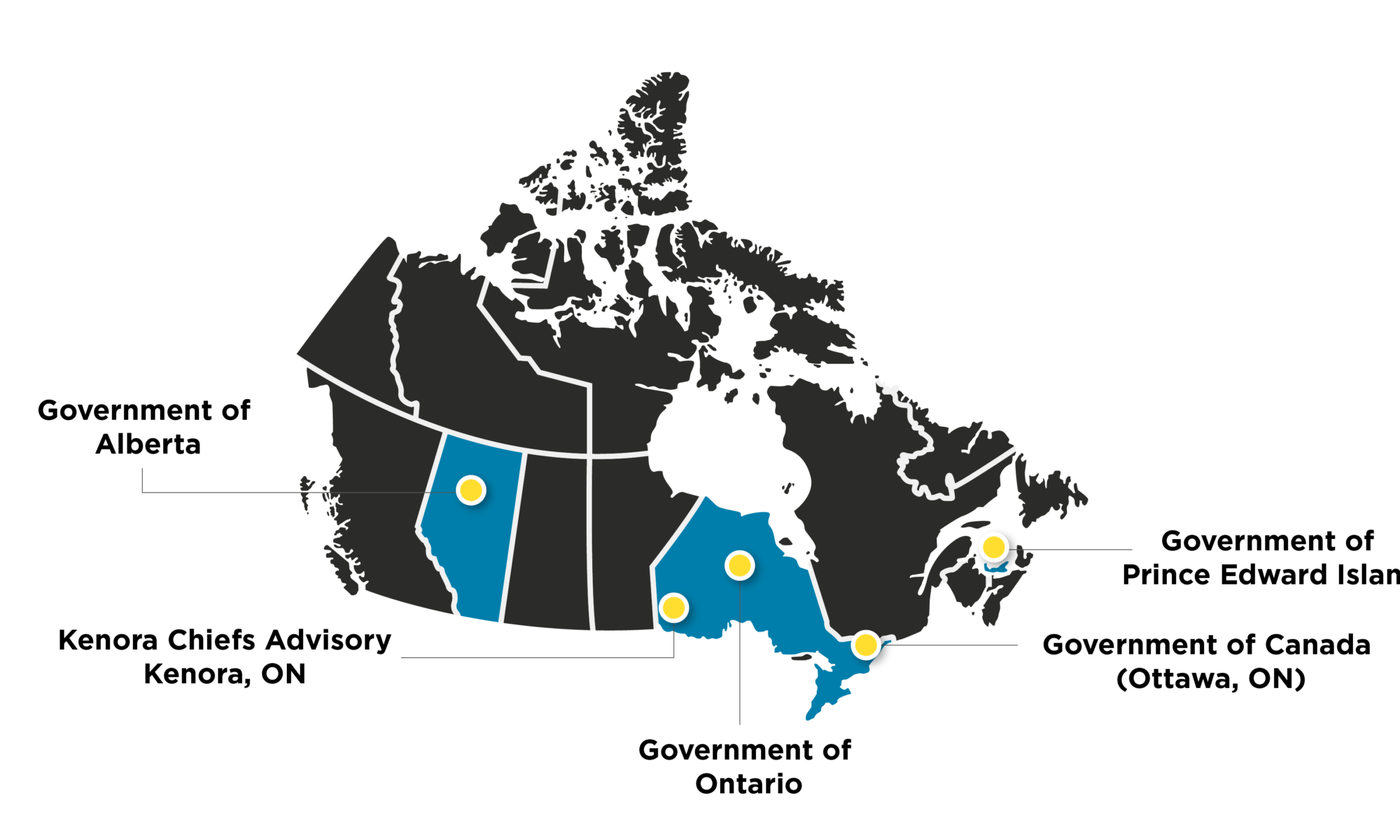

The Government of Canada, The Wilson Foundation, The Lawson Foundation and Microsoft.