Report 1: The Waiting is the Hardest Part

Series | COVID-19 Vaccine Skepticism in CanadaThe waiting is the hardest part

-Tom Petty

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was officially declared 10 months ago, in March 2020. For many, this seems like a lifetime ago. The virus has taken a substantial toll, not only in deaths, but also in the costs people around the world have incurred since its emergence. Yet with vaccine development and approvals happening at breathtaking speed, there is a light at the end of the tunnel.

Canadians have made great efforts in response to COVID-19, with the majority engaging in various social distancing measures. But people are tired. For most Canadians, whatever hope comes from a vaccine will soon come up against the fatigue of waiting to receive a dose.

Realistically, we still have a long way to go. According to credible estimates, herd immunity will not be realized until approximately 70% of the population is vaccinated. Vaccines will be slow to arrive, with the majority of Canadians not being vaccinated until the end of the third quarter of 2021. We are 10 months into the pandemic, and there are 10 months to go. This is half time.

This report examines Canadian attitudes toward social distancing, government response and COVID-19 vaccines. While retrospectives on the performance of federal and provincial governments will follow at the end of the pandemic, we find that governments have enjoyed broad agreement from Canadians that the pandemic is the most important issue, above all others, and that extraordinary efforts should be taken to combat it. But such support may not last forever.

Policymakers face three challenges as we move into a vaccination phase of the pandemic:

- First, they must maintain as much social normality and economic activity as possible. Schools should remain open where possible, manufacturing should continue, entrepreneurs should be able to sell their goods and services, and consumers should feel confident about the economy in the short and medium term.

- Second, they must encourage as much compliance with public health measures, including social distancing, broadly conceived, as possible. Through constant, everyday actions, citizens must continue to keep the virus at bay, especially as more infectious strains emerge.

- Third, governments must maintain the broad social consensus that COVID-19 is an issue above all others, until we achieve universal protection against the virus.

The rub is, governments must do all of this for a sustained period of time, while citizens see a solution—vaccination—that is not widely available and will not be for some time.

To help understand the nature of this challenge, this short report does four things. First, it provides a data-rich picture of the degree of social distancing in Canada. In doing so, it makes clear two things: while Canadians have been engaging in social distancing, at first in notably high numbers, compliance has been uneven, and it is eroded by work demands and the desire to see family. Second, the report looks at public approval of government efforts against COVID-19 across Canada, which has slowly eroded after initial high levels in March. Third, the report briefly reviews the nature of current opinion towards vaccines in Canada. Fourth, it explores how these factors are related to one another, and in doing so raises important warning flags about how misaligned hopes about a vaccine could undermine both support for government efforts and willingness to maintain social distancing.

Data

This study relies on data collected through the Media Ecosystem Observatory, a collaborative effort of three research sites: The Centre for Democracy, Society, and Technology and the Social Dynamics Lab at McGill University, and PEARL at the University of Toronto. MEO was born out of the Digital Democracy Project, of which Public Policy Forum was an early funder and champion. Since the third week of March 2020, MEO has conducted more than 60,000 interviews of Canadians in over 29 waves of data collection, all focused on the social and political contexts and implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. A longer description of our research strategy is available at www.mediaecosystem.com.

Social distancing in Canada

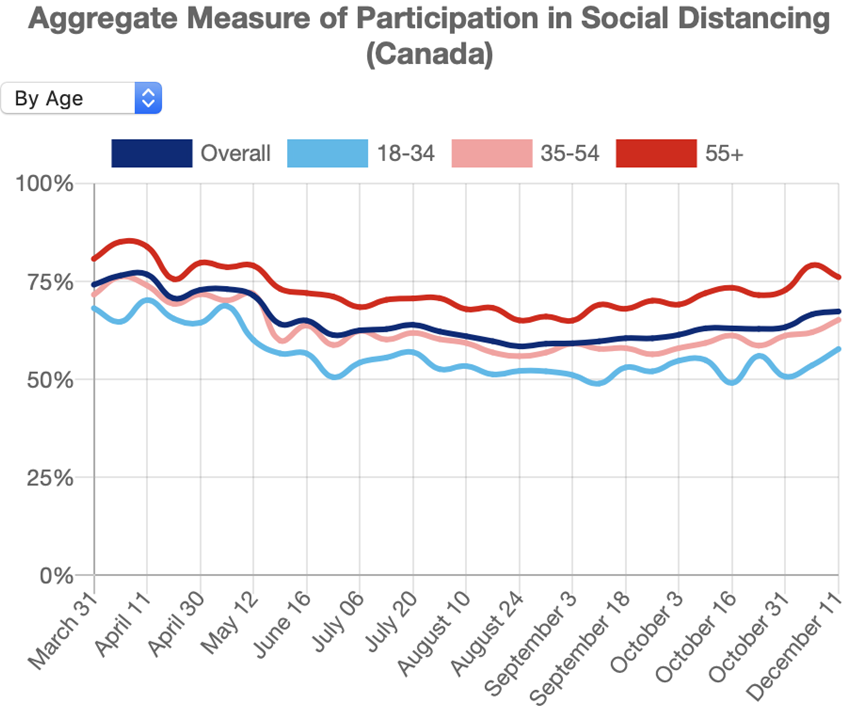

Figure 1:

Figure 1 demonstrates social distancing levels by age group from March to December 2020. The data are reported as an index, combining six different actions: avoiding crowded places; avoiding in-person contact with friends, family, and acquaintances; maintaining a distance of two metres from others; avoiding domestic travel; avoiding public transit; and avoiding the grocery store at peak times. Respondents are asked if they have taken the following precautions in the previous week. The graph displays the percentage of these measures taken by the average survey participant.

Two topline observations from Figure 1 are important. First, at the end of March 2020, the average Canadian reported taking 75% of those precautions in the previous week. Whether this is a sufficiently high number to maintain a low reproduction rate of the virus is a difficult question. But either way, this figure represented the high-water mark of voluntary social distancing in Canada. That share declined to a low of 58% of Canadians in late August, and returned back to a level of 67% in early December.

Second, whatever changes have occurred over time—with social distancing compliance declining from 75% to 58% (some 17 percentage points)—the more persistent and often larger difference is generational. At the end of March, the difference in compliance between those aged 55+ and those aged 18-34 was 13 points (81% vs 63%). By October 2020, the gap was nearly 25 points (73% vs 49%), as older Canadians were rebounding from their summer low in compliance, but younger Canadians continued at their nadir.

But related data make the challenge of social distancing more acute. First, in partnership with colleagues at the University of Guelph (Amy Greer and Gabrielle Brankston), we have periodically collected extremely detailed data on Canadians’ social contacts, in the form of “contact diaries.” These are accountings of how many people a Canadian has had close contact with, particularly being in physical contact or close speaking contact. Comparing data from May, July, and September, it is clear that Canadians have maintained low levels of contact in their home lives. But not at work. By September, Canadians began noticeably expanding their contacts in places of work. For many, there was likely little choice.

Second, Canadians have made exceptions—perhaps ultimately costly ones—over the course of the holidays. From January 11-15, MEO asked 984 Canadians, “Did you meet in-person and indoors with members outside of your household over the holidays?” More than a quarter (28%) reported meeting with family and friends from outside of their home in-person and indoors . Of this 28%, sixty-eight (68%) reported meeting with 1-4 such people, while 23% reported meeting with between 5-10. One in 10 (9%) reported meeting with more than 10 people.

The upshot of all of this is that Canadians are engaging in social distancing, but large generational differences exist, and we have fallen off of our best efforts. Canadians are making compromises for work and for family—compromises which many would judge as reasonable given the length of the pandemic and the difficulty of maintaining social distance.

Support for the government efforts against COVID

From the beginning of the pandemic, Canadian opinion towards COVID-19 has been characterized by a large degree of cross-partisan consensus on both the threat posed by the coronavirus and the importance of governments actively combatting this. (Merkley et al., 2020). This deep well of support has afforded governments the ability to pursue aggressive fiscal action—deficits be damned—and to ask citizens to forgo everyday activities that they may value very highly, not to mention key social services like non-emergency medical care or school for children.

MEO has been actively tracking citizens’ approval of government actions against COVID-19 (which should be understood as empirically distinct from political support for a particular government). Since the end of March 2020, MEO has asked Canadians whether they approve of how each level of government (the federal government, their provincial government, and their local government) is handling the coronavirus pandemic so far. To obtain a net approval score, participants’ answers were coded as follows: strongly approve (1); somewhat approve (0.5); neither approve, nor disapprove (0); somewhat disapprove (-0.5); and strongly disapprove (-1). We then averaged all scores across respondents.

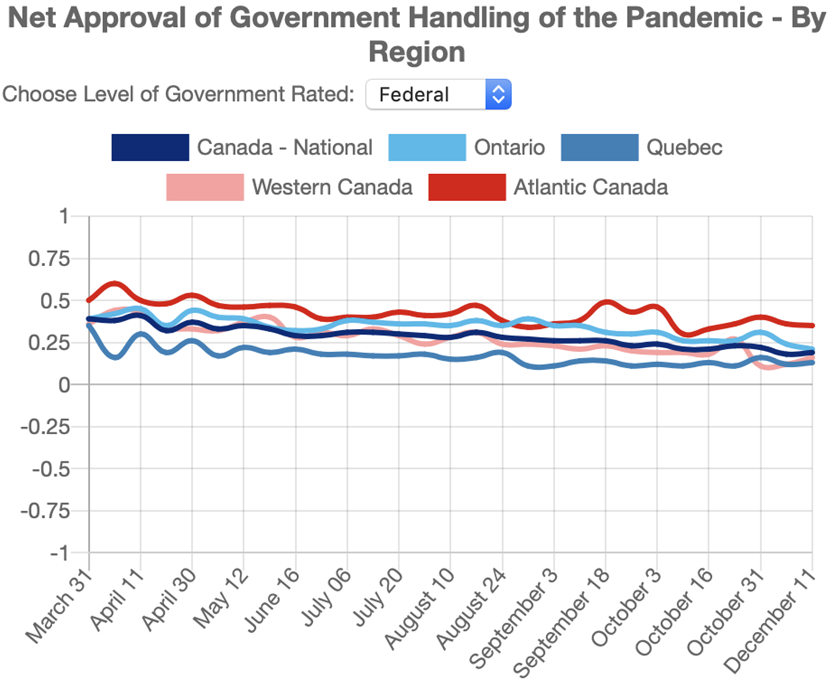

Figure 2:

Figure 2 displays the average score for the federal government by survey wave for each region in the country. The story is one of beginning from a position of high net approval, followed by a steady erosion. In every region of the country, approval of government efforts was high in March 2020. To wit, net scores were 0.50 in Atlantic Canada, 0.39 in Ontario, 0.36 in Western Canada, and 0.35 in Quebec. Scores in every region have declined, falling to 0.21 in Ontario, 0.16 in Western Canada, and 0.13 in Quebec. Even in Atlantic Canada, they have fallen to 0.35.

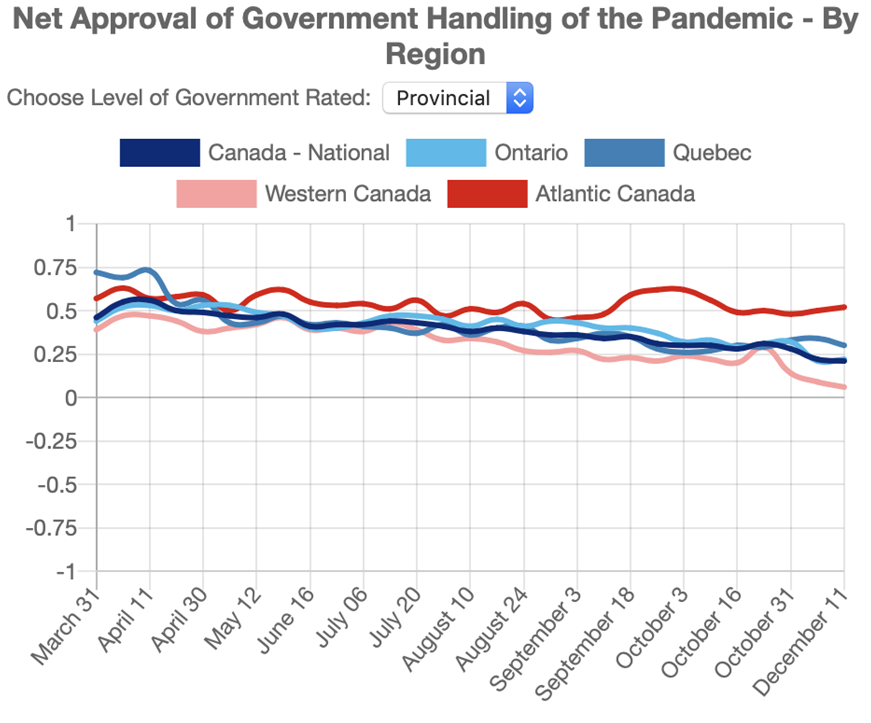

Figure 3 displays scores for respective provincial governments. Here again, support for government responses to COVID-19 was strong in March: 0.72 in Quebec, 0.57 in Atlantic Canada, 0.44 in Ontario, and 0.39 in Western Canada. By December 11, those approval scores had declined to 0.30 in Quebec, 0.52 in Atlantic Canada, 0.22 in Ontario, and 0.06 in Western Canada. Paul Simon is occasionally as good an analyst of politics as he is a songwriter: “The nearer your destination, the more you’re slip sliding away.”

Figure 3:

Vaccine opinions in Canada

In December of 2020, MEO released a report on vaccine hesitancy in Canada. Among its observations, four are most relevant to this report. First, opinions on vaccines are largely stable in Canada. The share of Canadians willing to take a vaccine has, since June 2020, remained relatively steady at approximately 65-70% of Canadian adults. Among the remaining 30% of Canadians, most are unsure about vaccines, while a hard core of one in five Canadians are set against taking a vaccine. We have not seen an increase in vaccine hesitancy, but nor have we yet seen a decline.

Second, among both those who will not take a vaccine and those who are unsure, safety is the principal concern. These two groups, however, disagree strongly over whether COVID-19 is a serious enough health risk. It is a major explanator for those unwilling to take the vaccine, but does not factor for those who are unsure.

Third, there are multiple factors that explain vaccine hesitancy, among them education, religiosity, age, gender, province of residence, anti-intellectualism, and conspiratorial beliefs. But the factors that do not structure opinion include generalized trust or right-left ideology. Properly understood and modelled, vaccine opinions are not yet related to the opinions most closely tied to partisan politics.

A final observation to add to this is that social distancing and masking are positively correlated with vaccination willingness. Citizens who follow government directives on maintaining social distancing are also those most willing to be vaccinated. This is good to the degree that it reflects a virtuous cycle of behaviour. It is bad in that it suggests that those, conditional on age and other underlying factors, who are most likely to spread the virus, ie. those who cannot and do not practice social distancing, are also among those least likely to take up the protection afforded by a vaccine.

Waiting for a vaccine

It is now clear that most Canadians will wait upwards of six months more before they receive a vaccine, as the majority of vaccinations are scheduled to occur in the third quarter of 2021. The data above may suggest, on balance, that we are prepared for such a wait. Social distancing is not universal, but Canadians are making efforts to continue. Support for governments fighting the pandemic remains more positive than negative. And citizens are positively disposed towards a vaccine, and demand should increase as those who are unsure see both its efficacy and the continued risk of COVID-19.

To hold on until vaccinations are sufficiently widespread, governments need only to convince citizens to maintain social distancing and to give their continued consent for various restrictions on their everyday lives. But there is a wrinkle. A non-trivial share of citizens are not convinced that we need to maintain these efforts for much longer.

In the second week of December, we asked our respondents: “For how long do you think it will be necessary to keep each measure in place to control COVID-19?” The various measures included social distancing and good hand hygiene; self-isolation for those experiencing systems; testing; contact tracing; and quarantining at home for those who test positive. Respondents could choose a time for how long each would be necessary, ranging from “End immediately” to “12-24 months” or “Until a vaccine is found.” For the purposes of analysis, I divide up respondents on each item according to whether they think a practice will need to be maintained for less than six months or for more.

Averaging across all five actions, 26% of respondents think that these actions will be required for more than six months. Importantly, belief that these actions will not be required for long is already correlated with a lack of social distancing and a lack of masking. Those who wish to cut short these actions are also less approving of their governments’ actions against COVID-19. And perhaps most importantly, those who are less prepared to wait are also less enthusiastic about a vaccine.

The challenge for governments, then, is this: How can they at once induce high levels of social distancing, government support, and vaccine willingness, while convincing an increasingly skeptical and tired public that they need to wait longer than expected for vaccines which are already rolling out en masse in other jurisdictions? The waiting is the hardest part.

References

Merkley, E. et al., 2020. A Rare Moment of Cross-Partisan Consensus: Elite and Public Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique, 1-8.

Owen, T. et al., 2020. “Understanding vaccine hesitancy in Canada: attitudes, beliefs, and the information ecosystem.” Available at: https://files.cargocollective.com/c745315/meo_vaccine_hesistancy.pdf

Thank you to our partners

NSERC

University of Toronto, PEARL

Trottier Foundation

Johnson & Johnson

Media Ecosystem Observatory