Report 3: Do Vaccine Brand Preferences Exist?

Series | COVID-19 Vaccine Skepticism in CanadaIntroduction

The Canadian approach to vaccine procurement has been to purchase large volumes of vaccines from multiple producers. Unable to rely on domestic manufacturing capacity, unsure of the integrity of global supply chains, and conscious of the global race to procure vaccines, the Canadian government has spread its bets across multiple vaccines. Indeed, no other country has secured as many vaccine doses per person as Canada. Federal regulators have approved for use four vaccines—Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca, and Johnson & Johnson—one more than the United States.

This strategy of heavy procurement and broad regulatory approval means that when vaccines are sufficiently available, Canadians may feel they should have a choice in which they receive.

Do Canadians actually care which vaccine they get? The answer is yes, and to a degree which may matter materially for the distribution of vaccines. In this short report, we present results from a recently conducted survey in which we explore Canadians’ preferences over both vaccine brands and vaccine characteristics. The results suggest that:

- Canadians prefer the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines to the AstraZeneca vaccine;

- Canadians evaluate the efficacy and safety of Pfizer and Moderna higher than AstraZeneca;

- Differences in brand preferences exist among those who are vaccine willing, not those who already express vaccine hesitancy; and

- The performance features of vaccines matter for Canadians’ vaccine preferences, and these effects are more pronounced among those already willing to take vaccines.

In presenting results on the public’s view of various vaccines, it is important to acknowledge that the public is not, as a whole, a scientific expert, and public judgements can never substitute for clinical trials. But public beliefs matter, because they guide behaviour. It is important that we understand what the public is thinking as we begin the process of mass vaccination.

Data

This report relies on data collected through the Media Ecosystem Observatory (MEO), a collaborative effort of three research sites—the Centre for Democracy, Society, and Technology, the Social Dynamics Lab at McGill University, and PEARL at the University of Toronto. MEO was born out of the Digital Democracy Project, of which the Public Policy Forum was an early funder and champion. Since the third week of March 2020, MEO has conducted more than 75,000 interviews of Canadians over 37 waves of data collection, all focused on the social and political contexts and implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. A longer description of our research strategy is available at www.mediaecosystem.com.

The data presented here were collected in our 37th wave, from February 24 to March 1, 2021.[1] We have 2,495 effective respondents, balanced by age, gender, and region. Respondents were recruited by Dynata to a survey hosted on the Qualtrics platform. Iterative proportionally fitted weights are generated using levels from the Canadian census and are applied to our data.

Analytical approach

The results we present rely on two sets of questions posed to our sample of respondents. First, to measure brand preferences, we asked Canadians the following:

- If you were offered the Moderna/Pfizer/AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine, how likely would you be to take it? (Very likely/Somewhat likely/Not very likely/Not at all likely).

- How would you rate the effectiveness of the Moderna/Pfizer/AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine? (Very effective/Somewhat effective/Not very effective/Not at all effective).

- How would you rate the safety of the Moderna/Pfizer/AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine? (Very safe/Somewhat safe/Not very safe/Not at all safe).

We randomize respondents to see only one brand for all three questions. To understand “brand effects”, we thus compare one set of respondents’ evaluations of one brand to another set of respondents’ evaluations of another brand.

Second, we conducted a conjoint experiment in which we asked respondents to consider two hypothetical vaccines side by side, with the vaccines varying on several characteristics.

The question wording for our conjoint experiment was:

In the following section we will provide you the characteristics of several hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine candidates. Please read the information carefully. We will ask you questions about them after each set of profiles.

Respondents were then presented with two profiles, where the attributes of each vaccine – country of origin, effectiveness against serious illness, risk of minor side effects, etc – are populated from plausible values for each variable. An example of the question is as follows:

Imagine the following vaccine candidates are in the process of being mass produced for public use.

Table 1: Hypothetical vaccine profiles presented to respondents.

| A | B | |

| Country of origin: | USA | UK |

| Effectiveness against severe illness or death from COVID-19: | 85% | 95% |

| Effectiveness against symptomatic coronavirus infection: | 65% | 85% |

| Effective against new variants of the coronavirus: | No | Yes |

| Risk of minor side effects (e.g. fever, chills): | 1 in 100 | 1 in 2 |

| Risk of major side effects (e.g. severe allergic reaction): | 100 per million | 20 per million |

We then asked respondents how likely they would be to take each vaccine, how safe it is, and how effective it is. This was repeated two more times, so each respondent saw six vaccine profiles in total. We use a linear regression model for each profile to estimate the “average component marginal effects” for each vaccine characteristic.

Results

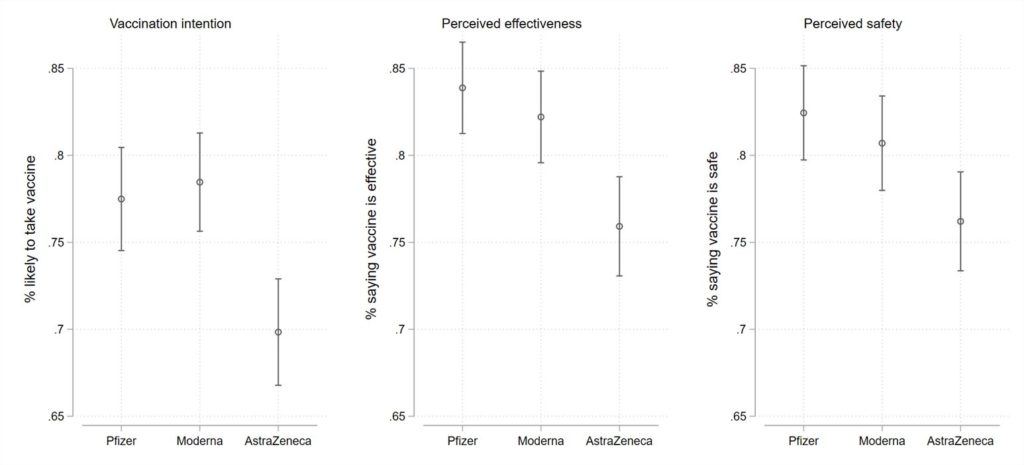

Figure 1: Vaccination intention, perceived effectiveness, and perceived safety by vaccine type, all respondents.

To begin, Figure 1 demonstrates three different outcomes by vaccine brand: the percentage of Canadians very or somewhat willing to take a vaccine if offered, the percentage regarding a vaccine as effective, and the percentage regarding a vaccine as safe. Among all respondents, the percentage indicating that they are very or somewhat likely to take the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine is 77% and 78%, respectively. By contrast, the share indicating that they are very or somewhat likely to take the AstraZeneca vaccine, if offered, is 70%.

These differences in uptake rates are underwritten by differences in perceived effectiveness and safety. Among our respondents, the share who perceive the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines as effective is 84% and 82% respectively. It is 76% for AstraZeneca. A similar difference emerges for perceived safety, where 82% and 81% of respondents respectively regard Pfizer and Moderna as safe, where only 76% regard the AstraZeneca vaccine as safe.

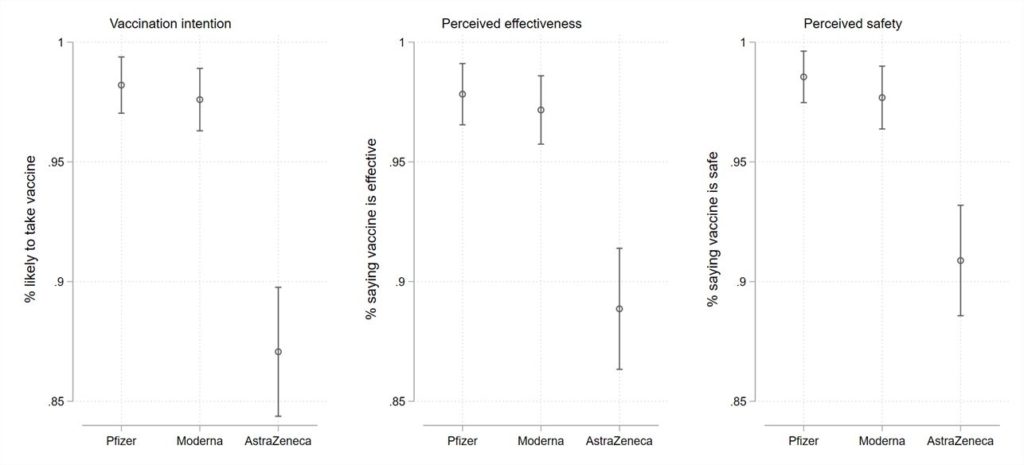

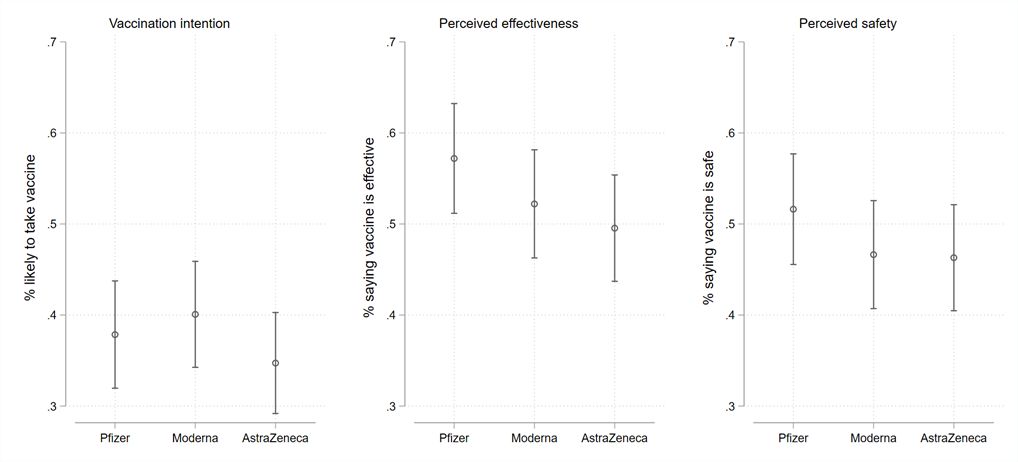

These results suggest that there are important, but perhaps not substantial, brand differences. However, these results are taken among all respondents. When we perform the analysis according to respondents’ baseline willingness to take a vaccine, larger brand differences emerge, and they do so among those Canadians who express a general willingness to take a vaccine once one becomes available. Figure 2 demonstrates brand preferences among the vaccine willing. While such Canadians are overwhelmingly likely to take a Pfizer or Moderna vaccine if offered (98% and 98%, respectively), that number declines to 87% willingness for the AstraZeneca offering. Similarly, perceived efficacy declines from 98% and 97% of respondents for Pfizer and Moderna respectively to 89% for AstraZeneca. Perceived safety shows similar differences, ranging from 99% and 98% respectively for Pfizer and Modern to 91% for AstraZeneca. As Figure 3 shows, similar brand differences do not exist among vaccine hesitant respondents. Across the board, they express they are less likely to take any vaccine, and they express markedly lower levels of perceived effectiveness or safety.

Figure 2: Vaccination intention, perceived effectiveness, and perceived safety by vaccine type, vaccine willing respondents.

Figure 3: Vaccination intention, perceived effectiveness, and perceived safety by vaccine type, vaccine hesitant respondents.

Individual-level Characteristics

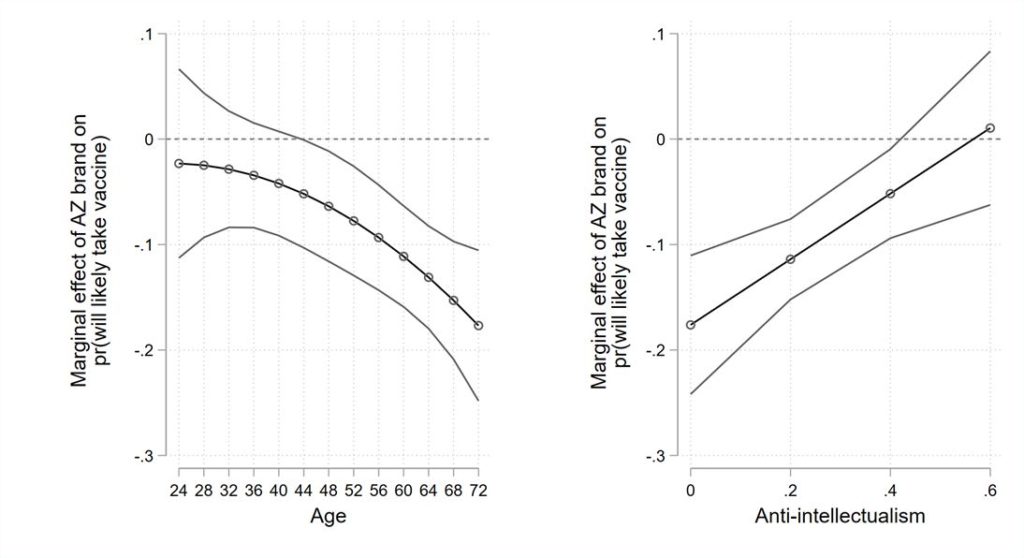

To better understand vaccine preferences, we present two more analyses. Our first goal is to understand what individual-level characteristics are underwriting marginally greater reluctance to use the AstraZeneca vaccine. Importantly, the AstraZeneca offering does differ from Pfizer and Moderna in its effectiveness for older Canadians, as demonstrated in randomly controlled trials. Indeed, federal usage guidelines for AstraZeneca have reflected this difference. Accordingly, we may find that both older Canadians and those who are more disposed to defer to scientific advice demonstrate a greater aversion to the AstraZeneca offering. This is indeed what we find, as demonstrated in Figure 4. The left panel in that figure demonstrates how much less likely a respondent is to indicate a willingness to take the AstraZeneca vaccine compared to the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines, according to their age. For respondents up to approximately age 44 there is no statistically significant negative effect. However, as age increases beyond that point, we find that respondents are measurably less likely to indicate a willingness to take the AstraZeneca offering compared to Pfizer or Moderna vaccines. Indeed, the effect is substantial among older Canadians, with our modelling suggesting that a 72-year-old respondent is 18% less likely to accept the AstraZeneca vaccine.

Figure 4: Effect of age and anti-intellectualism on willingness to take the AstraZeneca vaccine.

In our right panel, we consider whether respondents who are more likely to trust experts are less likely to take accept the AstraZeneca offering versus Pfizer or Moderna. We rely here on the concept of anti-intellectualism. This concept, which my colleague Eric Merkley has pioneered, measures the trust of individuals in scientific experts and expertise. We have previously shown, for example, that this psychological trait was a major predictor of mask uptake in response to changing federal recommendations on mask usage. Our results in the right panel of Figure 3 suggest that this trait also matters for vaccine brand preferences.

The brand penalty for AstraZeneca is greatest among those who show the most trust in scientific expertise. This penalty decreases as trust in scientific experts decreases.

In short, comparative reluctance toward the AstraZeneca vaccine is not seen among the generally vaccine hesitant or among those who reject scientific direction. Rather, it is higher among those most likely to take vaccines and those most likely to trust experts.

Characteristics of Vaccines

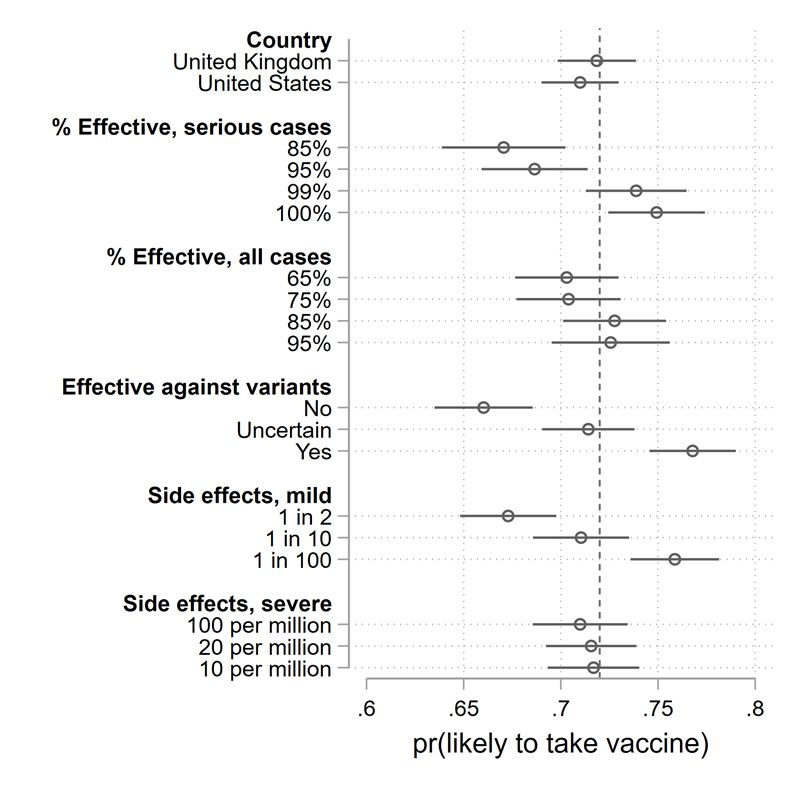

Second, moving beyond brand preferences, we wanted to more deeply explore the characteristics of vaccines which might increase or decreases willingness to take a vaccine. Because vaccine characteristics vary, it is difficult to understand preferences only in reference to brands. Accordingly, to get a better understanding of the effectives of different characteristics, we conducted a conjoint experiment presenting individuals with a series of different vaccine profiles, which varied according to their country of origin (the United Kingdom or the United States), the effectiveness against serious cases and their effectiveness against all cases, the effectiveness against variants, their rate of mild side effects, and their rate of severe side effects.

Figure 5 presents our results, estimated across all respondents. For explanation, the circles represent the estimated percentage of respondents willing to take a vaccine according to a characteristic, averaged across all other dimensions. The horizontal lines are estimated confidence intervals. The vertical dashed line indicates the mean willingness to take a vaccine average across all characteristics. Accordingly, a circle to the left of the line indicates that a characteristic decreases the likelihood of accepting a vaccine, while a circle to the right of the horizontal line suggests the factor increases likelihood above the average.

Figure 5: Effect of vaccine characteristics on willingness to choose a vaccine, all respondents.

When considering all respondents, it is clear that some vaccine characteristics matter, while others do not. Among the factors that do not matter for the average Canadian’s willingness to take the vaccine are the country of development (the United States versus the United Kingdom), or the incidence of severe side effects (when presented at rates ranging from 10 per million to 100 per million). Other factors do matter, however. Performance against serious illness matters markedly. A hypothetical vaccine with 85% effectiveness against severe illness is chosen with a probability eight percentage points less than one with 100% effectiveness. Effectiveness against all illnesses, on the other hand, matters but only marginally. Protection against mild side effects matters, though this was measured with substantial range, from 1 in 2 cases to 1 in 100. Perhaps the most impressive factor guiding vaccine preferences among all respondents is protection against new variants. A vaccine which is effective against a variant of concern has a 77% likelihood of being taken. This falls to 66% for one which is not effective against new variants.

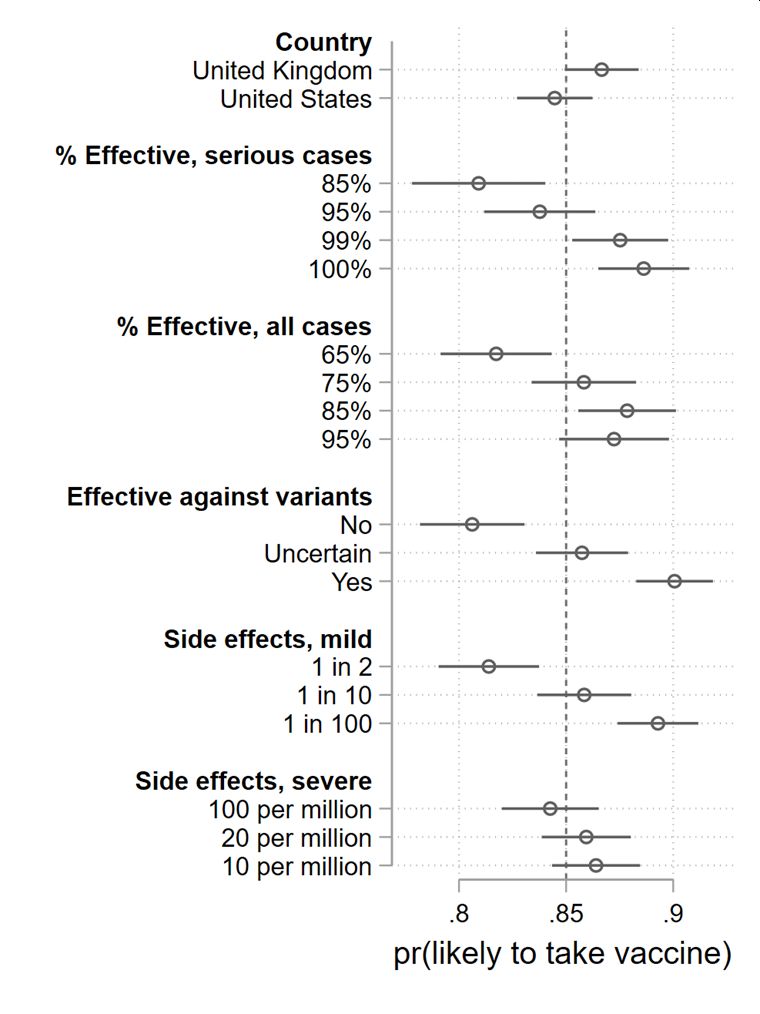

In Figure 6, we repeat this analysis, but limit the estimates to those respondents who told us earlier in the survey that they are willing to take a vaccine. We see similar effects, with one nuance. As with all respondents, severe side effects do not matter, but mild side effects do. Country of origin matters marginally, with a small preference for a UK versus American vaccine (contra AstraZeneca brand penalties). Effectiveness against serious cases once again matters, but so does effectiveness against all cases. What matters most, again, is effectiveness against variants.

Canadians with a baseline willingness to take a vaccine are 10 percentage points more likely to take a vaccine if it is effective against new variants versus one which is not.

Figure 6: Effect of vaccine characteristics on willingness to choose a vaccine, vaccine willing respondents.

Implications

The Canadian vaccine procurement strategy has been, in brief, to buy an excess of vaccines and to do so from multiple suppliers. The volume side of this strategy has had mixed results, though it is not clear that going with a single supplier would have increased volume. Purchasing from multiple suppliers insured Canada against failures in a single vaccine supplier or technology. The upside of this is that Canadians can now receive one of three vaccines, and soon one of four.

The challenge is two-fold. Different vaccines have different characteristics and Canadians have preferences on these characteristics. Accordingly, a major potential challenge in our vaccination campaign will be convincing vaccine recipients that the best vaccine is the one that is on the table in front of them, and it is not worth the wait for another. This challenge is only compounded by the fact that those who have the strongest vaccine preferences are those who are already inclined to take vaccines and who follow science more closely. This is one further complication in an already difficult vaccination campaign. It should not be ignored.

Footnotes

- We underline that our study went into the field prior to the federal government’s approval of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. ↑