Job Polarization in Canada

Series | Skills for the Post-Pandemic WorldKey TakeAways

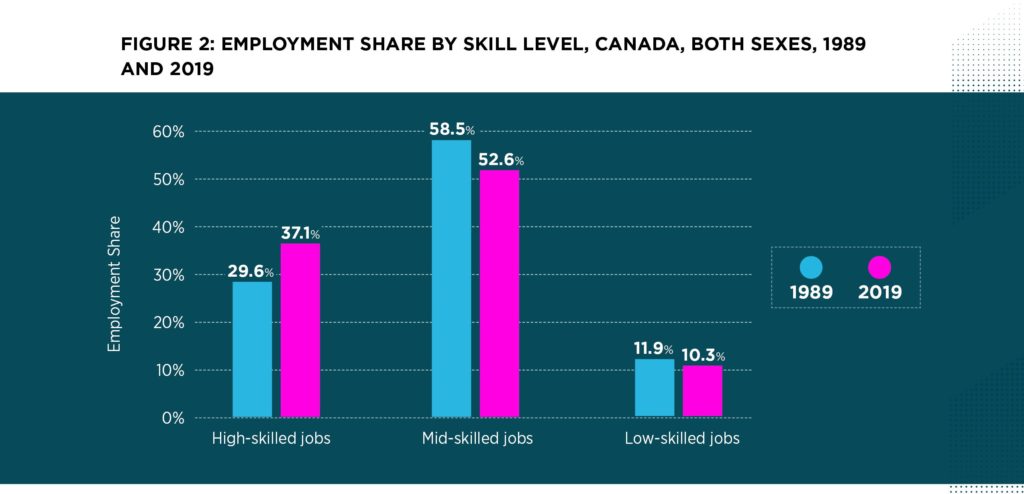

- Data show that the share of mid-skilled jobs in Canada have continuously declined over the last 30 years. While the share of high-skilled jobs increased during this period, the share of low-skilled jobs has remained flat, averaging 10.8 percent in subsequent years. The polarization of the Canadian job market can therefore be best described as creating a “J-shaped” economy.

- It appears that job polarization has different effects on different population groups. Female employment in high-skilled jobs has increased more rapidly than for men. Youth and recent immigrants are significantly more likely to engage in low-skilled jobs. However, data limitation makes it difficult to understand job polarization over time for racialized Canadians, Indigenous people, disabled Canadians and members of other groups.

Executive Summary

Significant changes over the past 30 years in the share of low-, mid-, and high-skilled jobs in Canada’s economy represent an underexplored labour market trend. During this period, Canada has seen a continuous decline in the share of mid-skilled jobs and a steady increase in high-skilled jobs. The share of low-skilled jobs has moved slightly up and down at times but has basically been flat since 2000.

Canada’s experience is not that different from most other advanced economies over this period. Indeed, most peer countries have experienced an increase in the proportion of high-skilled jobs, a reduction in mid-skilled jobs, and an increase in low-skilled ones. This trend is commonly referred to as “job polarization.” As policymakers look to build back economies after the pandemic, these long-term shifts are important to understand and consider, particularly when high-skilled jobs pay, on average, almost four times what low-skilled ones do.

This report looks at job polarization, with the goal of helping Canadian policymakers and the general public better understand the trend, including causes, effects and how it differs among provinces, industries and workers. The goal is to facilitate a discussion and debate about these trends, what they mean for Canada’s economy, and what public-policy changes could help to minimize the more negative economic and social effects of the so-called “vanishing middle.”

Source: Authors’ calculations based on employment data from Statistics Canada. (2020). Table 14-10-0335-01 Labour force characteristics by occupation, annual.

Job polarization has been under way in Canada over the past three decades, though this country’s experience is less marked than the OECD average. On the whole, Canada has seen a 7.5-percentage-point increase in high-skilled occupations and declines in mid- and low-skilled ones. These changes have not been uniform across provinces. Ontario and Quebec saw mid-skilled jobs decline by more than 7.5 percentage points while British Columbia and Nova Scotia saw drops of six and five percentage points respectively. Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Prince Edward Island have actually experienced small increases in the proportion of mid-skilled jobs in their economies, though the national average still trends towards a decrease in the proportion of the population working in these kinds of jobs.

Polarization also appears to have differing effects depending on the population group, though data gaps limit how much can be said about these differing effects. Statistics Canada, therefore, has a role to play in expanding its data collection and releasing more disaggregated data to the public to improve the understanding of how polarization differs for racialized Canadians, Indigenous people, disabled Canadians and younger workers, for example.

The need for further study is underscored by the fact that the way job polarization manifests itself in Canada is complicated. In addition to differences among provinces and populations, it is more pronounced in some industries than others.

But one thing is clear: The changes to the distribution of jobs represent a major economic, political and social development as there is less demand for the mid-skilled worker in the modern economy. Economists David Green and Benjamin Sand have warned that: “The loss of good jobs with wages that could provide financial security for less educated workers raises the spectre of an increasingly unequal society.” And an unequal society can create unrest – as it has in the U.S., where it seems to have contributed to the rise of political populism.

What can be done?

Policymakers should think about how they can create a new generation of middle-class jobs, an exercise that should transform today’s low-skilled jobs into more mid-skilled ones. This could be done by finding ways of furthering the education and training of low-skilled workers, and investing in productivity and modernizing labour market standards to reflect new and emerging forms of employment.

Policy can also play a role in helping to close the gap between people’s credentials and skills and the market’s recognition of them. This could include work on foreign-credential recognition, and reforms to labour regulations to address barriers such as discrimination. Other public policy steps, such as the expansion of childcare for working families could also make a big difference. But such changes will not happen overnight and will require buy-in from employers. Expanding vocational education and micro-credentialing to help those in low-skilled jobs keep up with changing labour-market demands are also avenues worth exploring.

As they turn their minds to post-pandemic planning, these ideas — and others that will emerge with more study — will be important for policymakers to consider.

Thank you to our partners

Skills for the Post-Pandemic World series is funded by the Government of Canada’s Future Skills Program

With support from