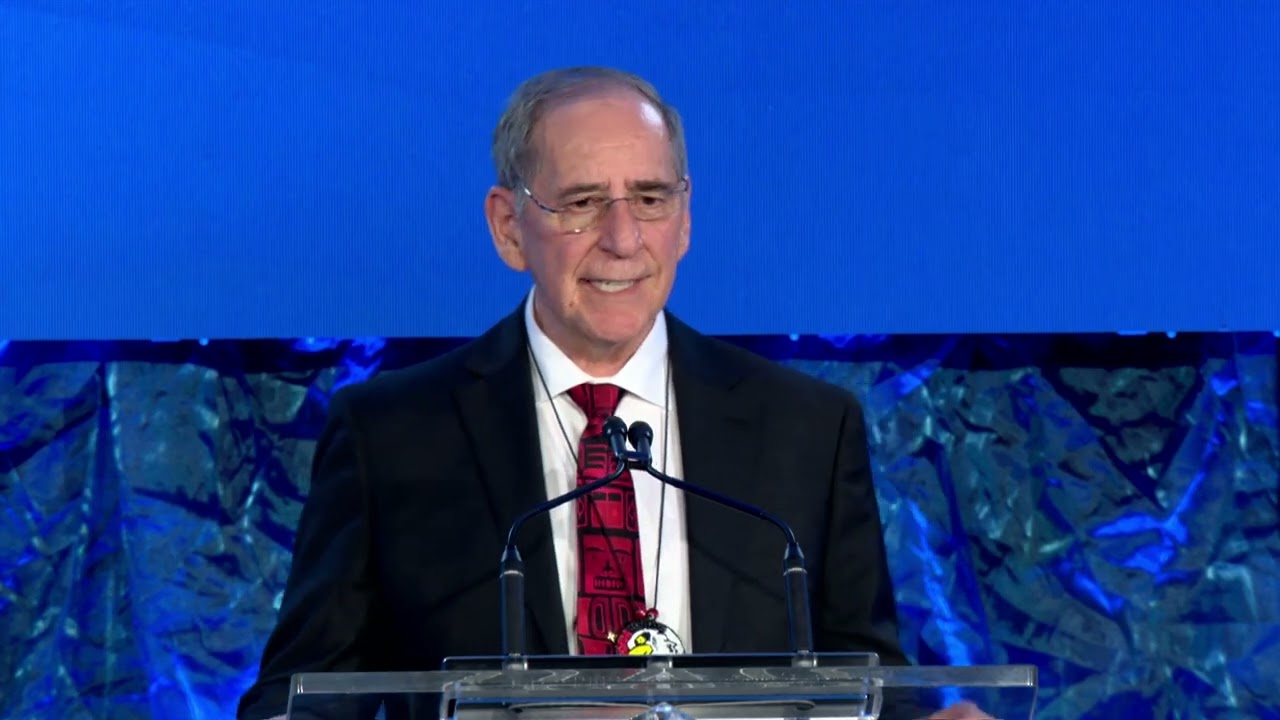

Harold Calla – 2023 Testimonial Dinner Award Honouree

Date: Tuesday January 17, 2023

Photography by Blair Gable

Harold Calla: “Providing the platform to move from managing poverty to managing wealth”

As Executive Chair of the First Nations Financial Management Board, Harold Calla is bringing economic reconciliation to life

It was a meeting at the local bank in 1987, while he was working for the Squamish Nation, that put Harold Calla on a career path that would make him a leader in Indigenous economic development.

Calla was born and raised in North Vancouver, adjacent to but not on the reserve, his mother a member of the Squamish Nation. He became a certified general accountant (CGA) in large part out of familial duty, to help the family cement company, but he went on to work for more than 10 years in international business, gaining experience in finance, manufacturing and distribution. In the mid-1980s, a cousin who was the director of post-secondary education for the Squamish asked if he could tutor a couple of young students looking to become accountants. Calla soon realized he wanted to come back to work in his community.

Also see: Harold Calla: Creating a seat at the table

Now here he was, the CFO of the Squamish Nation, meeting with a banker to arrange a loan. It should have been a simple matter — a short-term 30-day loan to cover a potential overdraft at the end of the fiscal year. But he was told he would need a letter from the federal minister of Indian Affairs backing the request.

“I had been a CGA for 10 years, I had been in the private sector, and I was able to make these kinds of decisions six months earlier, and now, all of a sudden, I couldn’t? I found that very offensive,” he recalls. “It was the first time I had sat across from anybody and was spoken to as an Indian. And I didn’t like it.”

It was a small example of the kind of paternalism Indigenous Peoples have suffered in Canada. They had been banished from the mainstream economy in countless ways over the centuries — denied legal rights and even permission to leave reserves, unable to own property or levy taxes on their own lands. Harold Calla has spent his life finding ways and building institutions to help First Nations take control of their economic destiny. He’s a trailblazer in what has become known as economic reconciliation.

It helped that Squamish Chief Joe Mathias took him under his wing. “I was one of the first professionals to come home, certainly the first professional in accounting, and those skills sets were something that could be used by the Squamish Nation looking at its economic development and political future,” he says.

At the time, Mathias and the Squamish were part of an effort to develop a modern treaty process in British Columbia. Calla was charged with helping to figure out what the tax and fiscal provisions of such treaties might look like. “It became clear we could not thrive and realize our economic potential if we remained under the Indian Act,” says Calla. So, he got involved in advising on federal legislation that would allow First Nations to opt out of certain provisions.

From there, Calla was instrumental in developing the First Nations Fiscal Management Act — the legislation that has defined his career ever since. Passed by the Paul Martin Liberal government in 2005 — though Calla proudly notes it had all-party support — it gives First Nations access to capital in a way that facilitates Indigenous ownership and creates opportunity for greater integration into the Canadian economy.

The act created the First Nations Financial Management Board (FMB), of which Calla is the executive chair, and the First Nations Finance Authority. The FMB is a nearly $2 billion pool of capital that First Nations can borrow from to finance development projects and business ventures. The Management Board helps develop a “financial administration law” establishing the processes and governance controls that the band will follow. It also examines five years of audited statements and awards a “financial performance certificate” if the band hits certain benchmarks. Bands need both things to borrow from the Finance Authority; so far, some 343 of the 579 Indian Act bands have asked to go through the Management Board process and be “scheduled” to the Fiscal Management Act.

It was this process that allowed a coalition of seven Mi’kmaq First Nations to borrow $250 million from the Finance Authority to buy a 50 percent stake in Clearwater Seafoods Inc., one of Canada’s biggest Indigenous business deals to date. The Management Board process gives outside investors and lenders reassurance to engage in true partnerships with First Nations. It can help grease the skids for projects that might otherwise stall or turn acrimonious, something that can send international capital to look elsewhere for opportunity. “Access to capital is important for us to come to the table as meaningful partners,” says Calla. “This can’t be left to the generosity of the private sector.” Together with the emergence of ESG (which demands companies invest based on sound environmental, social and governance principles), “there’s an even greater importance for inclusion of Indigenous communities in the decision-making process around project approvals and economic participation,” he adds.

And access to capital gives First Nations the opportunity to build their own economies. “We often describe ourself as providing the platform to move from managing poverty to managing wealth,” says Calla. More prosperous and healthy First Nations will be a benefit to all Canadians, he notes, in part because Indigenous Peoples are the fastest growing segment of the population in a country that needs workers, but also because economic reconciliation is not a zero-sum game. Strong First Nations economics will mean strong regional economies and a stronger national economy.

Having the tools to build their own economies is critical as well to Indigenous self-government. For economic reconciliation to proceed, Calla says, “there needs to be a nation-wide understanding and belief that Indigenous rights and title do exist. They weren’t extinguished. So, this is not pandering to Indians, if I can be blunt. This is about recognizing rights-holder interests, and working with rights holders to achieve common goals and objectives.” The fact that the Fiscal Management Act was driven by Indigenous Peoples is evidence that “First Nations can create solutions they can bring to the table.”

For Calla, the job of building economic capacity will continue. There’s interest in creating a First Nations asset management unit and a business development bank — and the need for more capacity to manage data. “Those are the kinds of things that we are going to need in the future to sit at the table with Canada as an equal.”

“Reconciliation is about more than righting past wrongs. It’s also about what you do going forward,” he adds. And he’s heartened by the reception these efforts have received. “We’re having the kinds of conversations that wouldn’t have happened 10 years ago.” It’s a long way from that unpleasant conversation in the local bank 35 years ago. “I never thought I’d see (this change) in my lifetime, to be very frank.”

Profile by Mark Stevenson

2023 Honourees:

Naila Moloo | John Risley | Lisa Raitt | Stephanie Nolen | Janice Stein | Laurent Duvernay-Tardif