How Canada can best respond to the U.S. trade war

A quantitative analysisDonald Trump’s long threatened tariffs on Canada came into effect this week. The question on everyone’s mind is: How did we get here? Over many decades, Canada and the United States have built one of the largest and most mutually beneficial trading relationships in the world. Over almost four decades, we have signed three free trade agreements with the U.S., with over $1.3 trillion in merchandise crossing the border in either direction in 2024, to the benefit of both nations. But the Trump administration’s unilateral tariffs have reversed decades of trust and jeopardized economic growth in both countries.

Since Trump was sworn in for a second time, we have been assessing the potential impact of tariffs on both the United States and in Canada. PPF has asked Navius Research, a non-partisan consultancy that focuses on quantitative analysis, to simulate the effect of those tariffs with its proprietary economic model. We’ve assessed how damaging the U.S. tariffs will be on both Canada and the United States as well as analyzed potential Canada-led strategies to respond to Trump’s tariffs. From these analyses, a few messages have become clear.

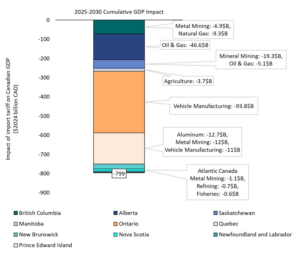

All Canadians are in this together. Unlike many other policies which disproportionately affect or impact one Canadian region more than another, U.S. tariffs on Canadian goods consistently reduce growth in every Canadian province. Each Canadian province has sectors that benefit from the close trade relationship with the United States. When tariffs are introduced, output from those sectors either declines or experiences price reductions (see Figure 1). This is true whether you look at gasoline and diesel refined in New Brunswick, aluminum exported from Quebec, steel and automobiles from Ontario, potash and uranium from Saskatchewan or oil and gas from Alberta.

Figure 1: Economic impact of US tariffs on Canadian goods

Paradoxically, some Canadian sectors could benefit from the tariffs. But these benefits should not be taken as nuggets of good news, but as a guide for how to better insulate Canada’s economy in the future. The sectors that see neutral-to-positive GDP growth in the face of U.S. tariffs are ones where trade already flows east-west rather than north-south — either trading between provinces or with countries other than the United States, in Asia and Europe. LNG production on the west coast and offshore oil production in Newfoundland uniquely see increases in economic output despite U.S. tariffs as they have access to broader markets and can reap higher prices abroad. The lesson here is clear and should be extended beyond these sectors. Greater trade networks to either the east or west coast will help insulate Canada from trade shocks with the U.S. and can act as leverage for the next tariff threat.

Before discussing options for retaliatory tariffs, it is important to highlight that no one wins a trade war. The United States will weaken its own economy and make life more unaffordable for Americans by implementing tariffs on Canada. Likewise, any retaliatory tariffs implemented by Canada will likely slow our economic growth as well. Therefore, we need to understand that the objective of our retaliation is not to boost our economy in the face of tariffs, but to strategically inflict more damage on the U.S. economy that we inflict on our own.

To inform Canada’s response, we analyzed the effect of a 25% retaliatory tariff on imports of U.S. goods into Canada on 23 classes of goods (each tariff was simulated individually to isolate its impact). The analysis indicates the retaliatory tariffs that inflict more damage on the U.S. than on Canada and the tariffs which Canada should avoid (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Net impact of 25% retaliatory tariffs on select commodity groups

Tariffs on U.S. goods can inflict more damage on the U.S. economy than on Canada under a limited but strategic set of circumstances. First, when Canada has adequate opportunities to substitute away from U.S. goods (i.e., a suitable domestic or non-U.S. alternative is available) we fare better. Alcohol imports from the U.S. are a perfect example of an opportunity to substitute away from the U.S. Canada has many options for alcohol other than the United States, including through interprovincial trade or from other countries.

Second, tariffs have a greater impact on the U.S. than in Canada if we have industries that are negatively impacted by U.S. tariffs and we have sufficient production capacity to meet our needs. Steel production in Ontario and Quebec are both negatively affected by U.S. tariffs and could export to other regions instead of the United States. Reciprocal tariffs on U.S. steel leads to a greater negative impact on the U.S. than in Canada.

Our analysis also hints at goods on which we should avoid imposing tariffs. These include goods used for investment purposes (e.g., machinery). These tariffs may negatively affect the United States, but they make investment in Canada more costly and further erode our productivity. As a result, the damage to our economy exceeds the damage to the U.S. economy, and lowers our global competitiveness.

Finally, we should avoid tariffs on goods that rely on highly integrated supply chains between Canada and the United States. Vehicles fit this description, despite Canada having many options for importing vehicles from outside of the United States. Our vehicle sector is too highly integrated with the United States to avoid the negative impacts of tariffs on Canada. In fact, the negative impact of vehicle tariffs was so disproportionately large on Canada, that they fall outside the figure.

The optimal response could extend beyond what was analyzed here. Policymakers do not need to be limited to a 25% tariff on a particular suite of goods. For example, raising the tariff above 25% on alcohol and tobacco may enhance the level of damage on the U.S. economy relative to Canada’s.

This analysis points to a potential path forward for Canada in this difficult and unprecedented situation. First, the analysis clearly shows that we, as Canadians, have to stick together because Trump’s tariffs affect us all. We can’t afford to be split along regional lines, as Canada and Canadians are prone to do. Second, we need to trade more east-west than north-south – either build on what we can do within Canada and trade across provincial lines, or develop new markets in Asia and Europe. And third, to the extent that we hit back, we need to hit back on those sectors that hurt the American economy more than our own.

This was not a trade war that Canada sought or started. But by preserving our unity, building stronger national and global east-west relationships, and implementing smart strategic response, we can still come through this stronger as a country.

PPF Fellow Mark Cameron leads PPF’s Canada-U.S. project; Jotham Peters is Managing Partner at Navius and Brianne Riehl is Managing Director — both specialize in energy-economy models.