What is productivity? And why is it such a problem in Canada?

Robin Shaban is a PPF Fellow and Associate Partner with Deetken Insight.

Laura Adkins-Hackett is an economist with the Labour Market Information Council

Productivity is a core driver of GDP growth and living standards. The level of Canada’s productivity, which is typically measured as GDP per hour worked, ranks 18 out of all OECD countries. Further, the growth of Canada’s productivity also lags that of other countries.

Canada’s weak productivity performance has long been a topic of debate and worry. Recently, the Bank of Canada declared it a national ‘emergency.’ People have put forward a dizzying array of solutions to this problem, including striking a productivity commission, undertaking a comprehensive review of the tax system, supporting expansion for small businesses, increasing competition in Canadian marketplaces, bolstering Canada’s R&D ecosystem, supporting SMEs in adopting new technologies, encouraging AI adoption, promoting a national culture of pride in one’s work, and the list goes on. Many have also pointed out that there is no silver-bullet solution to our lagging productivity owing to the vast number of factors that contribute to it.

What’s more, many of the potential solutions to our substandard productivity performance are inconsistent and conflict with each other. For example, as Professor Barry Cross at Queen’s University points out, larger companies are shown to be more productive and invest more to improve their productivity, so helping businesses scale should be a viable solution. However, in markets that are dominated by oligopolies, large business often goes hand-in-hand with a lack of competition, reducing the incentive for firms to invest in their productivity.

Although the issue of Canada’s poor productivity performance can be complex, its importance is all the more salient in our current affordability crisis as many people in Canada are struggling to maintain their standard of living. However, this complexity makes it difficult for policymakers to chart a decisive path towards greater productivity, and raises the question of whether policy even has the power to shift our productivity performance in a meaningful way.

What is productivity growth and how is it measured?

In a broad sense, productivity is the amount of output the economy generates from a certain level of inputs. The type of productivity that is generally discussed is labour productivity, calculated as GDP divided by total number of hours worked in the economy.

While there are many ways economists go about measuring productivity, labour productivity is often the focus of policy conversation because of its more direct connection to living standards and the data used to calculate it is more accessible compared to other productivity measures.

The growth of labour productivity is about more than just labour. Economists have broken labour productivity growth into three different components: multifactor productivity growth, the growth of labour composition, and capital composition growth.

Multifactor (aka total factor) productivity is a critical yet ethereal component of Canada’s productivity story. It is the total output of the economy divided by both the labour and capital that goes into the economy and captures the intangible or “disembodied” aspects of productivity.

These intangible aspects of productivity are vast, and can include things like good management practices, scientific insights, and network effects, as well as the way businesses are structured and organized (like whether a business benefits from economies of scale), among others. Multifactor productivity growth reflects all the sources of productivity that cannot be directly attributed to workers or capital, making it a ‘grab bag’ of all sorts of other factors that influence the productive capacity of Canadian enterprises.

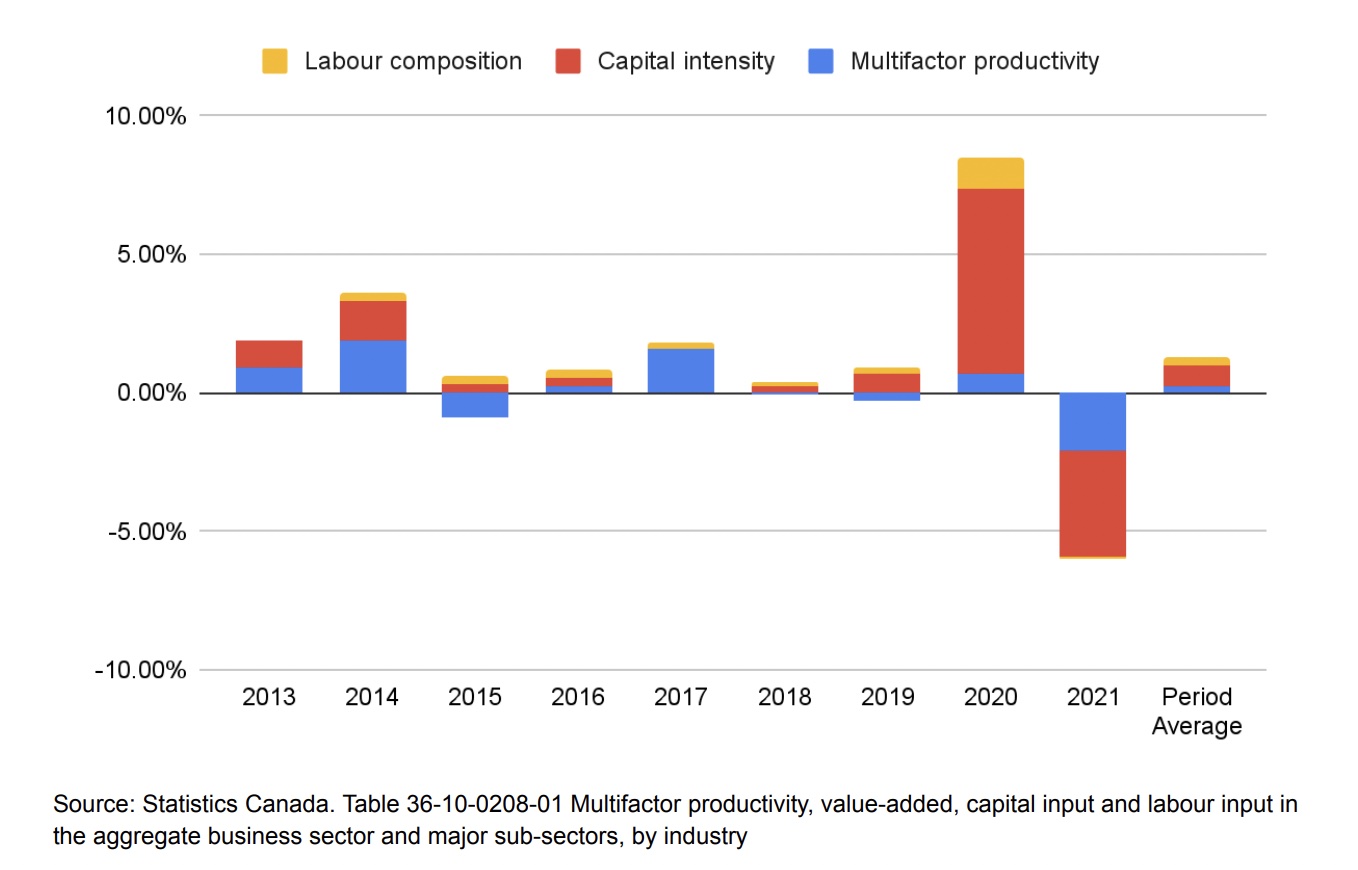

Since 2012, there have been some years where multifactor productivity has declined, creating a drag on top-line labour productivity growth. From 2012 to 2021, the average annual growth in multifactor productivity was 0.22 percent.

With the exception of 2021, the decline of Canada’s multifactor productivity growth has been compensated for by growth in capital intensity and labour composition. Labour composition, or labour quality, measures how much people can produce for every hour they work, which is influenced by personal characteristics like experience and education. Likewise, capital intensity reflects the performance of capital in the economy. It grows when people make investments into capital that deliver more output, such as equipment and technology, and fewer investments in long lived assets that generate less output, such as office buildings.

The onset of the pandemic saw a substantial increase in the growth of capital intensity, which has left a lasting impact despite being followed by a notable decline in 2021. Conversely, labour composition has consistently made a smaller contribution to labour productivity growth. On average, the annual growth of labour quality and capital intensity from 2012 to 2021 was 0.29 percent and 0.76 percent, respectively.

Zooming out to look at the trends from 2008 to 2019, declining capital intensity, particularly in information and communication technologies, was a contributing factor to weak labour productivity growth. After 2000, poor multifactor productivity growth has been the main cause of Canada’s lacklustre labour productivity growth.

How can productivity be improved?

The data highlight the sore points of Canada’s productivity performance, and gives some hints on how to enhance it. But these hints are far from providing a clear path forward.

Policymakers could certainly try to address these sore points directly. One way to do that is by encouraging businesses to spend more on research and development, which can lead to innovations that improve business technologies and practices. Some have critically pointed out that our weak productivity growth has persisted despite the many innovation programs the federal government has put in place. But it is not realistic to expect home-grown innovation alone to move the needle on Canada’s national productivity trends in a big way, especially over just a few years.

Furthermore, it is highly unlikely that government support will lead to the one blockbuster innovation that completely upends Canada’s productivity trend (although it would be great if it did). Rather, each innovation holds the potential to make a small, incremental improvement to our overall productivity, assuming Canadian businesses also adopt these innovations.

Another approach is for governments to sit back and let markets take the wheel. Firms in other countries, notably in the U.S., are leading in the adoption of innovative, productivity-enhancing technologies and business practices. So long as the Canadian border remains open to the flow of technology, investment and business know-how into Canada, Canadian businesses can import these productivity solutions rather than developing them themselves. Assuming there are no barriers to the free flow of these solutions, Canadian businesses could, in theory, become just as productive as their American counterparts. But for this approach to work, governments need to do their part to promote competition and trim business regulations that hamper business performance.

One thing commentators can likely all agree on is that there is no silver bullet solution to Canada’s disappointing productivity growth. If tools even exist for governments to tackle this issue in a meaningful way, approaches will need to be multi-pronged.

Ultimately, Canadians can take comfort in the fact that this problem is not unique to Canada, and that many other countries are also grappling with subpar productivity growth. Perhaps a path forward lies in working together with international peers to find solutions that bring prosperity to Canada and beyond. The more that we understand productivity and its drivers, the better we can ensure that the benefits of productivity are passed down to workers themselves, leading to wide-spread benefits for all Canadians.