Mission: Critical Minerals

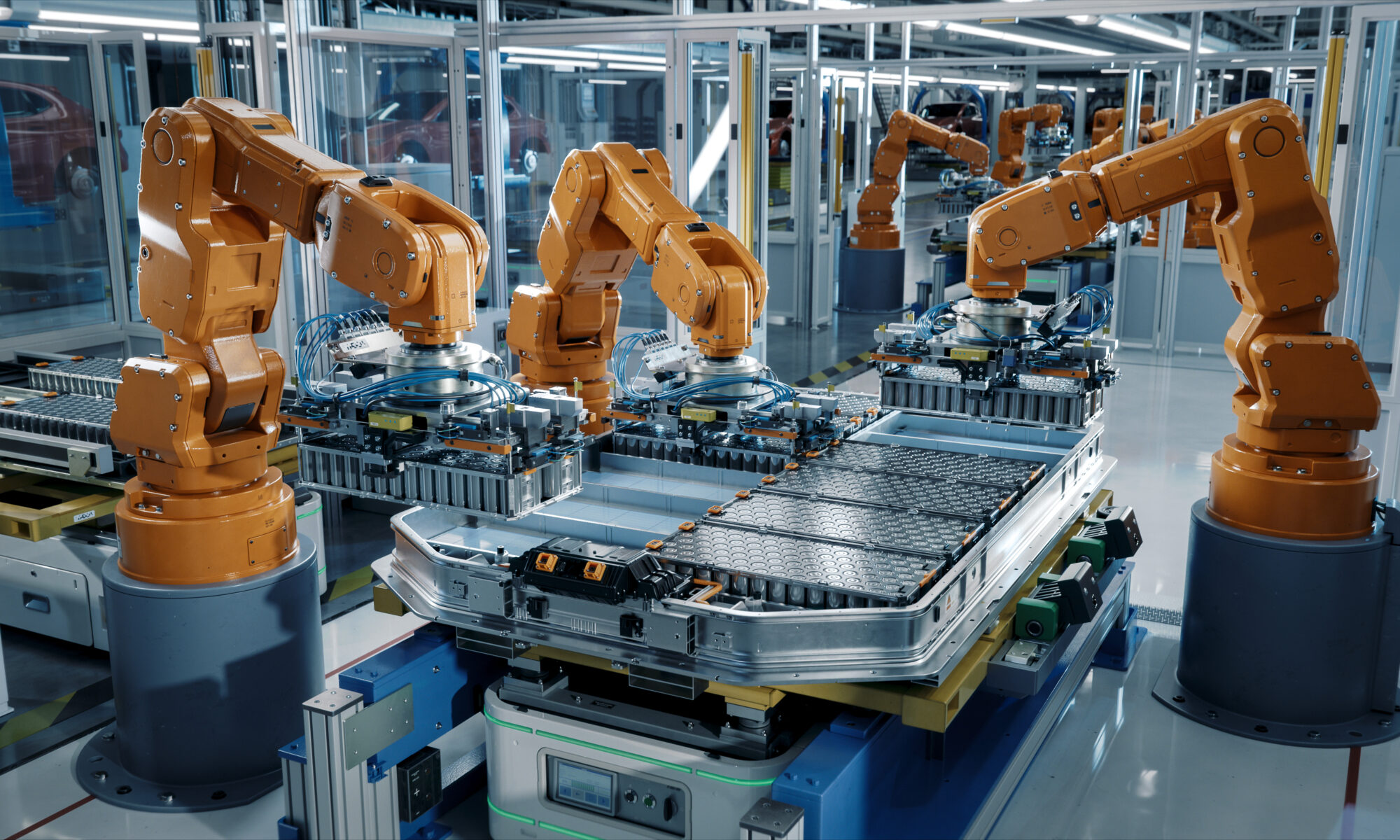

The transition to a clean and digital economy has ignited a global race for critical minerals — the essential inputs for batteries, electric vehicles (EVs), wind turbines, solar panels, advanced electronics and defence technologies.

These minerals (such as lithium, cobalt and nickel) are now as strategic to economic and national security as oil was in the past.

Demand is soaring worldwide, creating both a supply challenge and a once-in-a-generation opportunity for resource-rich nations. Canada, endowed with many of these critical mineral resources, aspires to become a reliable global supplier and clean-technology leader. In fact, leveraging Canada’s vast critical mineral resources could be a key driver for long-term economic growth.

The next few years will be crucial for Canada to ramp up extraction and build midstream processing capacity domestically. Even developing the major proposed critical mineral projects now in the pipeline could generate an estimated $80 billion in new investment and add over $500 billion to GDP over their lifetimes.

But there are significant barriers to be cleared — from market volatility and potential Chinese market manipulation, to regulatory and infrastructure hurdles.

The global scramble for critical minerals is already well underway. In May, the U.S. Department of Defence invested $20 million in a tungsten and molybdenum mine in New Brunswick — a sign of the growing strategic importance of this resource.

Canada needs to quickly advance strategies to secure critical mineral supply chains. In recent months, PPF hosted roundtables and discussions with industry, financial, government and academic leaders that have informed a few key recommendations. They include establishing a national reserve of critical minerals, innovative financing mechanisms and setting price floors — all with an eye to stabilizing prices and enabling investment.

This could be a nation-defining race that Canada can’t afford to lose.

Global demand for critical minerals is expected to grow explosively in the coming years, driven by the deployment of EVs, renewable energy, energy storage and other low-carbon technologies. Demand for lithium, cobalt and copper could increase almost fourfold by 2030, and by 2050 lithium demand alone may surge over 1,500 percent (with similar leaps for nickel and cobalt). Overall demand for these critical minerals could increase six-fold by 2040.

By mid-century, the market value of minerals needed for the energy transition is projected to reach around US$400 billion annually, exceeding the value of all coal mined in 2020. There is “no energy transition without critical minerals,” as the Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy notes — without these inputs, we cannot build the batteries, motors or renewable generators that a net-zero world requires.

Furthermore, with the rapidly accelerating role of artificial intelligence and the rapid build out of AI infrastructure, critical minerals are necessary for everything from microprocessors to fibre optic cable to copper wire in data centres.

Canada is exceptionally well positioned to benefit from this boom. A recent assessment by TD Economics estimated the in-ground value of Canada’s known reserves of just six key critical minerals (lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, graphite and rare earth elements) at over $300 billion. These reserves place Canada among the top 10 globally for each of those minerals by size. For example, Canada holds approximately 3 percent of world lithium reserves, 2 percent of cobalt and graphite and 1.7 percent of nickel.

Beyond raw resources, Canada brings other strengths to the table. It has a long-established mining industry with a skilled workforce and mining services companies that operate globally. Canada is home to nearly half of the world’s publicly listed mining and mineral exploration firms (albeit many of them small cap players) and has deep expertise in finding and developing mineral projects. It also boasts strong environmental and labor standards, which can make Canadian minerals attractive to buyers seeking ethically sourced inputs.

Moreover, Canada has a stable political environment and is a trusted trade partner to fellow democracies, a reputation that matters as countries look to “friendshore” their supply chains for strategic materials. All these factors underpin Canada’s ambition to be a “supplier of choice” for responsibly sourced critical minerals.

Recognizing the opportunity, the Canadian government has launched an ambitious Critical Minerals Strategy (December 2022) backed by nearly $4 billion in federal investments. The strategy explicitly aims to “position Canada as the global supplier of choice for critical minerals and the clean digital technologies they enable.”

Concrete steps have followed: Budget 2022 introduced a new Critical Mineral Exploration Tax Credit (up to 30 percent of capital costs) and a $3.8 billion fund to support mining infrastructure and development projects. Federal and provincial governments have also partnered with automakers and battery companies to build out downstream manufacturing that will use Canadian-mined minerals.

But being well-positioned is not the same as being fully prepared. Canada currently has only a handful of active mines producing critical minerals like lithium, cobalt or rare earth elements — most projects are still in development stages or all still awaiting regulatory approvals. It currently produces only about 1.9 percent of the world’s lithium and under 1 percent of its graphite, indicating substantial room to grow domestic output.

Critical mineral supply chains are geographically concentrated and vulnerable, leading to tight markets, price spikes and geopolitical risks. A handful of countries dominate production of key minerals: for instance, the Democratic Republic of Congo provides about 70 percent of the world’s cobalt, China produces around 60 percent of rare earth elements and Indonesia supplies 40 percent of nickel.

Processing and refining are even more concentrated, with China refining roughly 90 percent of rare earths and 60 to 70 percent of global lithium and cobalt. Such concentration leaves the world exposed to supply disruptions or export restrictions.

In 2010, for example, a sudden Chinese embargo on rare earth exports caused prices to soar by over 10-fold within a year, disrupting industries from electronics to automotive. More recently, pandemic-related supply chain shocks and the war in Ukraine have illustrated the fragility of critical mineral supply, contributing to record price swings. For instance, lithium carbonate prices spiked to all-time highs in late 2022 before crashing by over 60 percent in China by mid-2023 and have declined further since then.

Several major barriers must be addressed to unlock Canada’s critical minerals potential. They include:

Price Volatility and Market Uncertainty: Many critical minerals are “emerging or niche commodities” with opaque markets dominated by a few suppliers, leaving them highly susceptible to disruptive trade practices and price swings. Cobalt prices spiked to decade-high levels in 2018 only to crash the next year when oversupply hit the market. Lithium has seen similar boom-bust cycles: after surging to record highs in 2022, lithium carbonate prices fell by roughly 70 percent within months as supply briefly outpaced demand. Such volatility can quickly render a mine uneconomic and scare off investors who fear that today’s high prices may not last by the time their project comes online. Without intervention, price uncertainty will continue to delay, and even cancel, critical mineral projects despite strong long-term demand.

Chinese Market Dominance and Manipulation: China is the world’s largest processor (and often producer) of many critical minerals — controlling an estimated 90+ percent of certain key minerals for energy transition technologies. Chinese firms (often with state backing) control large portions of global supply chains — not only by refining 60 to 70 percent of critical materials as noted, but also by aggressive mining investment abroad. In some cases, China has used this dominance to influence market prices and undercut competitors.

Chinese oversupply has at times flooded the market and crashed prices, as seen recently with lithium and nickel, which made it harder for new projects in North America to secure financing. This intentional price undercutting (“dumping”) keeps potential Western rivals out of the market. Conversely, China has shown it can restrict exports to exert pressure, as with rare earths in 2010, and more recently its export restrictions on gallium and germanium (critical for semiconductors).

As former Natural Resources minister Jonathan Wilkinson noted, “if China can simply intervene and crater the price, you will never see the development of the critical minerals that we have to.” Until there is more transparency and fair play in critical mineral markets, Canadian projects will be cautious. Canada suspects market manipulation and dumping is occurring in battery metals markets right now and has urged allies to develop alternative pricing mechanisms to counter China’s sway.

Canada faces an added dimension in strategic competition with China: Chinese companies have sought to invest in Canadian mines (e.g. for lithium and rare earths), raising questions about security of supply and intellectual property. In late 2022, Canada moved to bar or unwind certain Chinese investments in critical mineral projects on national security grounds, highlighting the risk of losing control over strategic resources.

Regulatory and Permitting Challenges: Developing a mine in Canada (as in many democracies) involves lengthy regulatory reviews, environmental assessments and consultations – processes vital for responsible resource development, but often slow and unpredictable. It can take over a decade from discovery to production. The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy itself acknowledges the need to “speed up regulatory decisions on critical mineral projects” if Canada is to compete.

Without streamlining, the complex federal-provincial permitting framework Canada risks missing the window of opportunity as other countries move faster to bring critical mineral supplies online.

Notably, Indigenous partnerships are both a moral imperative and a practical necessity: many deposits are on or near Indigenous lands, and projects can face opposition or legal challenges if communities are not properly consulted and benefiting.

Infrastructure and Geographic Hurdles: Many of Canada’s critical mineral deposits are in remote northern regions. Lack of all-season roads, rail links or grid power in proximity to mine sites raises the cost and complexity of development.

While the federal $3.8 billion Critical Minerals Infrastructure Fund and other programs aim to support building such infrastructure, significant gaps remain. Until road, rail spurs and grid connections are planned in a strategic way, many promising deposits will remain inaccessible.

Additionally, Canada currently has insufficient domestic processing capacity for certain minerals — for instance, no commercial-scale lithium refineries or rare earth separation facilities yet — meaning that even if mined, raw materials might have to be exported for processing (often to China) unless midstream facilities are developed.

Labour and Skills Shortages: While the mining industry employs around 200,000 people directly, a significant wave of retirements is underway and younger Canadians are not entering mining trades and professions at the needed rate. In fact, surveys show that two-thirds of young Canadians would not even consider a mining career, contributing to an estimated 10,000-worker shortfall. Critical minerals development will require not just geologists and miners to find and extract resources, but also metallurgists, chemical engineers and technicians to build and operate processing plants, as well as environmental and community engagement specialists. The risk is that even if Canada can finance and permit new critical mineral projects, who will build and operate them?

What will it take to move Canada from promising geology to commercial production and global leadership? The biggest challenges the sector faces are related to price volatility and financing issues.

Through consultations with key players in the industry, three key targeted policy tools emerge that could de-risk investment, when considered alongside the broader permitting, infrastructure, labour and Indigenous‑partnership measures examined above.

1. Build Strategic Mineral Stockpiles

Government-managed stockpiles (or “buffer stocks”) can help smooth out the extreme highs and lows of critical mineral markets. By buying minerals when supply is ample or prices are low, and releasing them during shortages, a stockpile acts as a shock absorber against unanticipated demand spikes or supply disruptions.

Japan, for example, created a rare metals stockpiling program in the 1980s and, after China’s rare earth embargo in 2010, significantly expanded its stockpiles and diversified supply — cutting its dependence on Chinese rare earth imports from 90 percent to about 60 percent within a decade. Canada should similarly evaluate building strategic reserves of critical minerals (possibly in coordination with allies) to guard against both physical shortages and wild price swings.

PPF’s Build Big Things: A playbook to turbocharge investment in major energy, critical mineral and infrastructure projects recommends government backed offtake agreements as one tool for encouraging critical mineral investment. A Canadian Critical Minerals Stockpile could purchase output from domestic producers during downturns (providing a guaranteed buyer of last resort) and hold these materials for emergency use or future sale. This would directly support Canadian miners through price troughs and help stabilize global markets.

International coordination could multiply the effect — for instance, a joint G7 or NATO stockpiling initiative could cover a broad range of critical elements. While carrying costs and storage considerations (especially for minerals that can be bulky or have limited shelf life) must be managed, the benefits of a well-designed stockpile in reducing volatility and ensuring supply security could outweigh the costs. It signals to investors that there is a backstop market, thereby encouraging more mine development.

2. Set Price Floors

To address the investment-dampening effect of price volatility, governments should provide price support mechanisms that reduce price risk and guarantee a minimum revenue for critical mineral producers. This could include a form of a price floor or guarantee which would compensate producers if prices fall below a certain threshold due to unfair market manipulation.

One model gaining attention is the use of contracts for difference (CFDs) — a tool borrowed from renewable energy financing — as a form of price floor. Under a CFD, the government would pay producers the difference between the market price and an agreed “strike price” (floor) when market prices are below that level, ensuring the project earns a stable minimum price. If prices exceed the strike price, payments could reverse (the producer might pay back into a fund or to the government), although designs can vary.

The effect is to de-risk projects by making future revenues more predictable. In essence, a CFD shifts some downside price risk to the public sector, which can absorb it more easily than a junior mining firm.

In Canada’s context, price floors could be set for critical minerals of strategic importance to guarantee producers a reasonable return on investment, potentially funded through the Canada Growth Fund (CGF). The CGF was established in Budget 2022 with a specific mandate to “capitalize on Canada’s abundance of natural resources and strengthen critical supply chains,” and was authorized to use offtake agreements and contracts for differences as financing tools. CGF has already announced one deal in the critical minerals sector (an investment in Nouveau Monde Graphite in Quebec).

3. Launch Innovative Financing Supports

Large-scale capital investment is needed to develop mines, processing plants and supporting infrastructure. Governments could spur this by leveraging creative financing tools and public-private partnerships.

One approach is for the government to co-invest in projects or provide low-cost financing to reduce the burden on private developers. Canada has already taken steps in this direction: the Strategic Innovation Fund and the Critical Minerals Infrastructure Fund ($3.8 billion) are being used to directly invest in enabling infrastructure and even take equity stakes alongside private or allied investors. Expanding such co-investment programs would spread risk and attract more capital into the sector.

Likewise, loan guarantees or insurance for critical mineral projects can improve access to credit. Export credit agencies (like Export Development Canada) and development finance institutions could be marshaled to support projects that have strategic value but might not get purely commercial financing due to market uncertainties.

Canada should also coordinate with allies like the U.S., European Union, and Japan to create a “critical minerals club” that facilitates joint investment and pooling of demand. This could include harmonized incentives and shared investment vehicles to finance new mines in each other’s countries or in third countries, ensuring those resources enter friendly supply chains.

Additionally, tax incentives can stimulate exploration and processing capacity — e.g., tax credits for critical mineral processing analogous to those for clean manufacturing, and accelerated capital‑cost allowances to catalyze high‑impact investments. The federal government already created a 30 percent Critical Mineral Exploration Tax Credit for targeted minerals like lithium and rare earths. This could be matched by a parallel Critical Mineral Development Tax Credit to offer a rebate or deduction on capital expenditures for building processing facilities or mining infrastructure, helping projects cross the finish line into production.

Allowing companies to write off investment faster would also improve project economics and attract investors.

Provinces can complement this with their own incentives — for instance, Ontario’s Junior Exploration Program provides grants to help fund early exploration, including a dedicated stream for critical minerals.

The federal government could also consider establishing a Critical Minerals Financing Facility — potentially through institutions like the Canada Infrastructure Bank or a new entity — that takes minority equity stakes or provides low-interest loans to promising projects. Canada has already put some money on the table in Budget 2022, announced a $1.5 billion loan facility for critical minerals and the Strategic Innovation Fund has earmarked funds for critical mineral projects, but ensuring these funds are accessible to junior miners is key.

As small companies struggle to tap large programs due to complex application processes or requirements, streamlining access and possibly bundling support (e.g. combining federal and provincial funds) can make a difference.

Public-private partnerships where automakers or battery companies invest in mining projects (with government backstop) should also be facilitated — this vertically integrates the supply chain and provides juniors a guaranteed buyer. Governments can incentivize such offtake investments by offering matching funds or loan guarantees.

Another potential financing tool would be commodity-linked bonds. A commodity-linked bond is a debt security whose interest (coupon) payments and/or principal are indexed to the price of a specific commodity. Unlike a normal fixed-rate bond, its value and payouts fluctuate with the underlying mineral’s market price. As the linked commodity’s price rises, bond investors receive higher payments; if the price falls, the issuer’s payment obligations decline in tandem. This ties the project’s debt service to its commodity revenue — when mineral revenues dip, the bond costs automatically ease, and vice versa. Such bonds could be tied to prices of specific critical minerals (e.g. lithium hydroxide, cobalt sulfate) or to a critical minerals or rare earth price index. This gives investors direct exposure to critical minerals’ upside while aligning a mining project’s financing costs with volatile market conditions. It effectively embeds a commodity hedge into the financing structure.

These policy solutions could form a toolkit to stabilize the market and encourage investment in critical minerals. It is important that such measures be designed in a transparent, rules-based manner to avoid unintended consequences or trade disputes, and be time-limited to address market failures rather than permanent subsidies.

Canada’s endowment of lithium, graphite, nickel, rare earths and more can be the foundation of a secure North American and global supply of these inputs, provided that government and industry act decisively. The cost of inaction will be high: without domestic critical minerals, Canada could see its electric vehicle and clean tech manufacturing ambitions stymied by import dependencies and supply disruptions.

Conversely, by investing now in supply chain resilience, Canada can reduce reliance on any single foreign supplier and gain a strategic edge in the emerging clean economy.

The window of opportunity is open but will not remain so indefinitely — other countries are moving fast to stake their claim in the critical minerals sector. Swift and strategic policy action, in coordination with allies, will ensure that Canada not only meets the global challenge of critical minerals, but prospers from it. This is mission critical.