Free Atlantic: Unlocking Regional Growth

Introduction

Liberalizing trade within Canada has long been a challenge. Geographic constraints, infrastructure gaps, differences in language and culture, and easy access to a large market to the south have all dampened the volume of internal trade. Concerns over limited interprovincial trade have surfaced repeatedly throughout Canadian history, from early infrastructure challenges at Confederation aimed at bridging these divides to issues of local protectionism in the 1930s and, more recently, to disputes over alcohol distribution, credential recognition and much more.

While these concerns have been a consistent thread in Canada’s history, the recent prospect of significant U.S. protectionism — and the potential loss of easy access to a large, previously friendly market — has raised serious alarms. Governments now recognize that efforts to diversify trade must be dramatically increased. This includes not only boosting international trade but also enhancing trade between provinces.

Prime Minister Mark Carney has signalled that this strategy involves addressing not only regulatory barriers imposed by the federal government that add to interprovincial trade costs but also making major investments in national infrastructure. And provinces have begun to seize this uniquely uncertain moment by advancing efforts to liberalize trade among themselves. This paper analyzes those recent efforts, with a focus on economic gains available to Atlantic Canada.

Before turning to a discussion of recent trade agreements in Canada — and the underlying data and quantitative analysis — it is important to clearly define what internal trade costs in Canada actually are. Unlike trade between countries, tariffs are not levied on economic transactions between provinces; this is explicitly prohibited by the Constitution. Instead, Canada’s highly decentralized federation has created internal trade costs not by design, but as an unintended consequence of enacting different rules, regulations, standards and certifications across jurisdictions.

A business seeking to buy or sell in another province may need to comply with multiple sets of regulations, which naturally raises the cost of doing business. This, in turn, creates a marginal disincentive to pursue such transactions in the first place. The same is true for businesses looking to operate across provincial boundaries. These seemingly small frictions can, at the margin, deter firms from scaling up to the level that their productivity might otherwise allow.

Internal trade frictions, therefore, act as a drag on productivity in much the same way that international trade barriers do. They enable relatively less productive firms to remain larger than they otherwise would be or, in some cases, to exist at all. These frictions are not so large as to prevent internal trade entirely — far from it. But they do matter at the margins, subtly shaping business decisions and reducing economic efficiency.

Currently, internal trade accounts for roughly one-fifth of Canada’s economy — significantly less than the share of international trade, which is nearly double. Before the early 1980s, internal and international trade volumes were roughly similar. But as international trade liberalization advanced, the share of economic activity represented by internal trade declined, while international trade’s share increased. A considerable body of academic research supports the existence of meaningful internal trade frictions in Canada. Studies suggest that these barriers may reduce Canada’s overall productivity by between four and eight percent.

As policymakers focus on easing internal trade frictions and capturing some of the associated productivity gains, increasing attention should be paid to the various strategies governments are using to pursue this goal. One proven approach involves regions liberalizing trade within a smaller subset of provinces. Past successes with this model suggest similar gains could be achieved in regions that have not yet adopted such arrangements. There have also been several memorandums of understanding (MOUs) between provinces to improve trade and labour mobility. This includes agreements between Ontario, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, another between Newfoundland and Labrador and New Brunswick, and most recently (at the time of writing) one between Ontario and Manitoba.

The goal of these agreements is to facilitate the movement of goods, the provision of services, investment, and worker mobility between the two economies in a more seamless way. Premier Susan Holt of New Brunswick emphasized that the aim of the MOU is to “ensure that all products, services and credentials that are approved by Newfoundland and Labrador are automatically recognized by New Brunswick, and vice versa.”[2] They have broad support across both provinces and the political spectrum, with provincial governments led by Liberal parties, Conservative parties and the New Democratic Party each committing to significant action.

These recent moves are especially encouraging as they represent a departure from past provincial practices of more limited liberalization. In 2017, for example, the Canadian Free Trade Agreement — then the most comprehensive effort to liberalize internal trade in Canadian history — aimed to harmonize regulations across provinces. However, the new MOUs between provinces have taken a different approach, committing to the mutual recognition of credentials, regulations, standards, certifications and more. This distinction is critical and could, if provinces follow through, mark the beginning of a new era of internal trade liberalization in Canada.

This paper illustrates the potential benefits of these new approaches, with a particular focus on Atlantic Canada. In recent months, the region has taken a leadership role in advancing trade liberalization through ambitious new agreements, with the prospects for deep regional integration growing stronger.

To preview the main findings: I estimate that goods traded between Atlantic Canadian provinces face, on average, trade costs equivalent to a tariff of approximately six percent. This aligns with national-level research by other scholars. However, trade costs for services are significantly higher: I estimate the average to be around 39 percent — a much steeper barrier than for goods. This disparity underscores the importance of credential recognition and the ability of professionals and service providers to operate across provincial boundaries, even when they are not locally registered. Credential recognition extends well beyond liberalization alone. Most of the economic gains associated with mutual recognition come from making it easier to trade services across provinces. The high trade cost for services in Atlantic Canada may also explain why services trade accounts for a smaller share of total trade in the region — approximately 40 percent — compared to the national average of about 60 percent.

The potential gains from reducing these internal frictions between Atlantic provinces are substantial. I estimate that a one percent decline in trade costs between provinces in the region could raise real GDP by approximately $200 million per year. Wages could increase by between 0.1 and 0.3 percent, depending on the province, and both employment and population could grow by between 0.1 and 0.4 percent. Policy-relevant measures could yield even larger gains. If Atlantic Canada were to implement changes similar to those in the New West Partnership— achieving trade cost reductions observed in comparable arrangements — real GDP could increase by $500 million. This would translate into per capita gains ranging from $140 in New Brunswick to $410 on Prince Edward Island. For the most ambitious scenario — full mutual recognition across all four Atlantic provinces — real GDP could rise by approximately $14.7 billion per year. The per capita gains could be substantial: $3,400 annually in Newfoundland and Labrador; $4,900 in New Brunswick; $5,900 in Nova Scotia; and as much as $12,600 per year on Prince Edward Island. These represent productivity gains of between 4.4 percent and 22.4 percent, depending on the province.

While there are several important caveats to these estimates, which are detailed throughout the paper, the conclusion is clear: meaningful reductions in internal trade costs can yield significant economic benefits for residents of Atlantic Canada — and, potentially, for Canadians more broadly.

Regional Internal Trade in Canada

This paper began by briefly outlining the relevance of regional internal trade agreements in Canada, which have often been the standard approach to liberalizing internal trade and overcoming regulatory barriers to economic exchange. I then provided a high-level overview of regional trade flows within and between the four Atlantic provinces. With this policy and data foundation in place, I’ll now estimate trade costs in the region, followed by an analysis of the economic impact of various forms of regional liberalization.

Regional Trade Agreements

Canada has entered into many regional trade agreements over the years. One of the earlier ones, adopted in 1989 by the four western provinces, aimed to ensure that government procurement processes were not overly biased toward local suppliers. Later, in 1994, Ontario and Quebec signed an agreement addressing labour mobility and government procurement. This was followed shortly after by the National Agreement on Internal Trade. Subsequent agreements focused on facilitating the mobility of construction workers — first between Ontario and Quebec in 1996 and then between Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador in 1998. Within Atlantic Canada, there were also region-specific agreements: one in 2000 related to certain vehicle weight regulations and another in 2008 concerning government procurement.

Among the most ambitious regional trade agreements ever enacted in Canada is the New West Partnership Trade Agreement (NWPTA), involving the four western provinces — British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and, most recently, Manitoba. The origins of this agreement trace back to a bilateral deal between British Columbia and Alberta in 2009 known as the Trade, Investment and Labour Mobility Agreement. The NWPTA currently seeks to facilitate the movement of goods, services, investment and workers between provinces.

While not without flaws, the agreement is promoted by the participating governments as creating the largest barrier-free interprovincial market in Canada. To achieve this, the jurisdictions committed to full mutual recognition or reconciliation of their rules concerning the movement of goods, people, services and investment. Although the commitment is ambitious and the agreement’s text is quite encouraging, there are many ways in which it has fallen short of true mutual recognition, and significant barriers remain between these jurisdictions. That said, recent research has measured — using statistical methods — the effect of the NWPTA on trade costs between the four provinces. The findings show that interprovincial trade costs declined by 2.3 percent. While this may not seem like a substantial drop, it represents a meaningful reduction in interprovincial frictions.

This estimate will be applied later in this paper to assess the potential gains for Atlantic Canada if it were to adopt a regional trade agreement of similar scope and with a comparable effect to that observed under the NWPTA.

Pattern of Regional Trade Flows

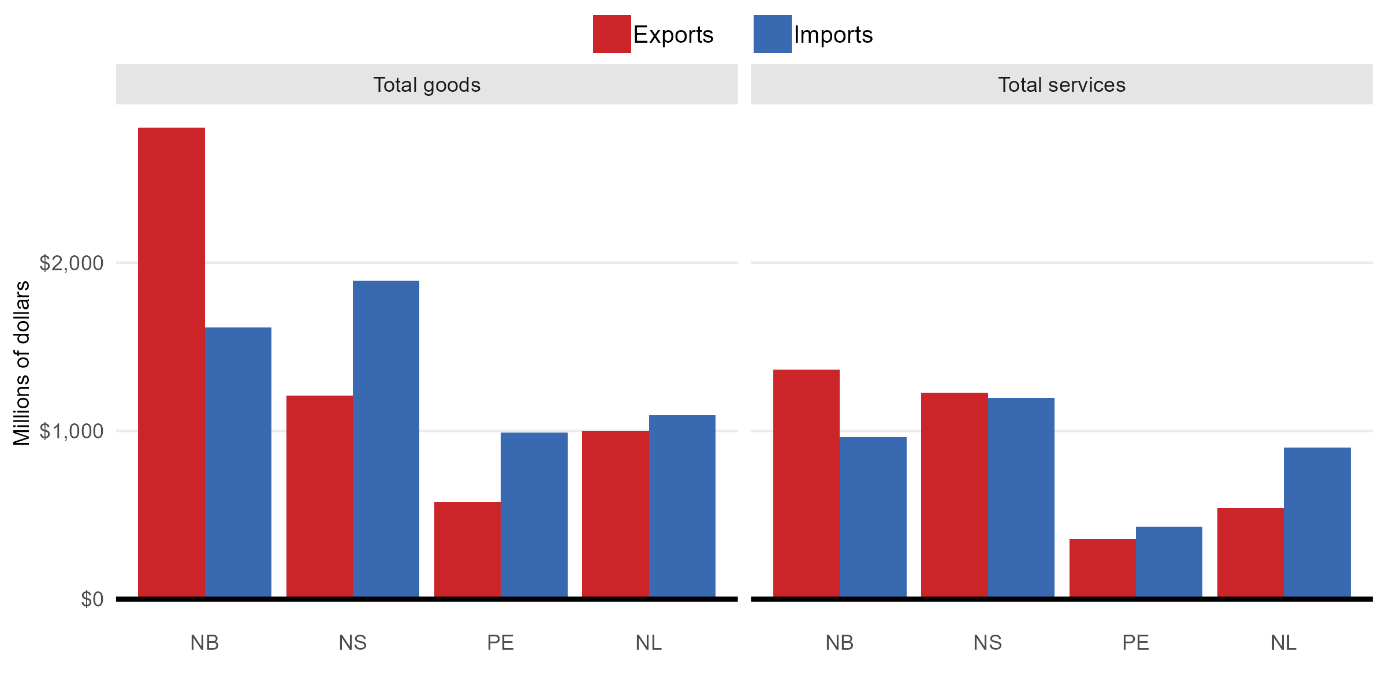

There is considerable trade volume between the four Atlantic provinces, based on the latest available data, as illustrated in Figure 1. The value of exports from each province to the other Atlantic provinces, and the imports from those provinces in return, varies across the region. In the case of New Brunswick, trade in goods shows exports exceeding imports. For the other provinces, imports tend to exceed exports. However, in terms of services, both New Brunswick and Nova Scotia have regional exports that surpass their imports.

The benefits of lower trade costs arise from both exports and imports becoming more efficient. The implications of this type of trade liberalization for economic outcomes — and the potential impact on provincial transfers — will be discussed later, as they depend on the direction of trade flows. Overall, approximately $9.1 billion is traded annually between the Atlantic provinces, representing around 6.5 percent of the region’s economy in 2021. Of this, about $5.6 billion consists of goods, while $3.5 billion comes from services. This distinction is important when comparing regional trade patterns to those of the national economy. Across Canada, interprovincial trade in services accounts for roughly 60 percent of total interprovincial trade, whereas in Atlantic Canada, services make up only about 40 percent.

In terms of goods, the most commonly traded items between the provinces include diesel, gasoline and conventional oil, followed by various fishery products, pharmaceuticals and animal feed. As for services, the largest component of regional trade involves wholesale margins — especially for machinery and equipment. Other key service categories include architectural and engineering services, building support services, administrative services and truck transportation.

| Figure 1: Interprovincial Trade Within Atlantic Canada (2021)

Note: Displays the value of inter-regional trade between Atlantic provinces in 2021. Source: Author’s calculations using Statistics Canada data table 12-10-0101-01. |

Alcohol, of course, receives significant public attention in any discussion of interprovincial trade. Within the region, approximately $90 million worth of beer was traded, followed by $6.8 million in wine. This is only about one percent of the total value of goods and services traded.

Quantifying Interprovincial Trade Costs

Inferring trade costs between provinces in Canada is no easy matter. Unlike tariffs between countries, interprovincial trade costs are not directly observable. They often take the form of non-tariff barriers arising from differences in rules, regulations, standards, certifications and so on. Providing jurisdictional compliance across provinces — especially when it involves adhering to different sets of rules and regulations around product safety standards — is costly for firms that wish to operate or trade across provincial boundaries.

However, a variety of methods have been developed to quantify the size of non-tariff barriers. Researchers have consistently used these methods across countries, and they have also been successfully applied within Canada. The details of these methods are not important for the purposes of this paper, but the underlying idea is relatively straightforward. If one observes a certain volume of trade between two jurisdictions, that volume can be compared to a counterfactual estimate of what trade would look like in the absence of all trade costs. If individual buyers — whether consumers or businesses — have similar goals and no inherent preference for locally supplied goods, a world without trade costs would see buyers in different provinces making identical choices in sourcing the lowest-cost goods or services. Any differences in actual sourcing decisions observed in the data can therefore be taken as indicative of the presence and size of trade costs.

To quantify how large these trade costs are to explain observed trade volumes, we need estimates of how sensitive trade flows are to trade costs. For items where trade flows are highly sensitive, only small trade costs are needed to explain limited trade volumes. Conversely, for items that are relatively insensitive to trade costs, a larger magnitude of trade costs is necessary to account for the same trade patterns. Estimates of the elasticity of trade — how responsive trade flows are to changes in trade costs — exist for highly detailed, product-level data across countries, and a well-known, dependable estimate also exists within Canada. If the sensitivity of trade flows to costs within Canada resembles what is observed internationally, we can apply those international estimates to better understand and quantify interprovincial trade costs.

One would not want to stop the analysis here, however, since measures of trade costs between Canadian provinces reflect a variety of factors that may or may not be relevant for policymaking. Time, fuel, labour and equipment required to ship a good from Vancouver to Halifax will always and necessarily be non-trivial. The frictions involved in simply learning about the availability, price, quality and other attributes of items in far-off markets also pose challenges for internal trade. In a country as vast as Canada, many fundamental contributors to interprovincial trade costs are difficult — if not impossible — for governments to address through policy, particularly in the short term.

Of course, infrastructure quality and the efficiency of our rail, port and road networks can help mitigate how much distance limits internal trade. However, for the purposes of this paper, the focus is on the size of interprovincial trade costs that result from regulatory differences rather than from infrastructure limitations. This distinction is particularly important within the Atlantic region, which — aside from Newfoundland and Labrador — occupies a relatively small geographic area that can, in theory, be more easily integrated through infrastructure compared to other parts of Canada.

To strip out the effect of distance from the overall size of trade costs, I follow an approach used in other research, which correlates measures of trade costs at the industry level with the distance between provincial jurisdictions. This provides an estimate of how much trade costs increase with each kilometre of separation. Using this estimate, I then remove the impact of distance, leaving what I refer to as “non-distance trade costs” — a measure that may be especially relevant from a policy perspective.

To be clear, these estimates rely on several underlying assumptions, which may or may not hold true in practice. Any estimate of non-tariff barriers is inherently an exercise in using assumptions to interpret data and infer fundamentally unobservable elements. As such, these estimates should be viewed as subject to potential error. For example, if people do have a strong preference for locally supplied goods or services, the method will incorrectly attribute limited interprovincial trade to high trade costs, when it may reflect differences in consumer preferences. Of course, this too is a matter of interpretation. Strong local preferences can themselves act as a barrier to trade by limiting the extent to which productive firms in one location can scale to serve broader markets. However, these are not trade costs arising from regulatory differences between jurisdictions. There is also statistical error inherent in estimating policy-relevant trade costs, given that the relationship between trade costs and distance carries its own margin of error. In the sections that follow, I report both upper and lower bounds for trade cost estimates where appropriate.

Estimates of Interprovincial Trade Costs

Using these methods, I estimate that the average interprovincial trade cost between the four Atlantic provinces — excluding the effect of distance on those trade costs — is approximately 21 percent. The confidence interval around this statistical estimate ranges from a low of 16 percent to a high of 27 percent.

| Table 1: Average Non-Distance Trade Costs in Atlantic Canada | ||||

| Destination Province | ||||

| Origin Province | New Brunswick | Newfoundland and Labrador | Nova Scotia | Prince Edward Island |

| Goods | ||||

| New Brunswick | 3.6% | 5.5% | 1.0% | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1.0% | 10.2% | 53.0% | |

| Nova Scotia | 9.6% | 5.7% | 9.3% | |

| Prince Edward Island | 11.4% | 9.7% | 17.7% | |

| Services | ||||

| New Brunswick | 37.7% | 53.9% | 42.9% | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 41.0% | 31.6% | 56.3% | |

| Nova Scotia | 57.1% | 36.3% | 71.6% | |

| Prince Edward Island | 51.2% | 43.5% | 77.3% | |

| All Items | ||||

| New Brunswick | 13.1% | 21.7% | 10.6% | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 9.6% | 20.5% | 55.8% | |

| Nova Scotia | 32.6% | 23.1% | 28.7% | |

| Prince Edward Island | 22.2% | 27.4% | 39.6% | |

| Note: Reports the average tariff-equivalent internal trade costs between Atlantic Canadian provinces

Source: Author’s calculations. See text for details. |

||||

There is also notable variation across types of items, with goods facing significantly lower interprovincial trade costs than services. Our estimate suggests that goods, on average, face trade costs equivalent to a tariff of approximately six percent, ranging from 3.4 percent at the low end to nine percent at the high end. By contrast, trade costs for services are much higher, averaging around 39 percent, with a range from 39.5 percent to 59.5 percent. That services face much higher trade costs than goods should not be too surprising. Internal frictions affecting services are typically more complex due to the hundreds of occupations and professions subject to local licensing requirements to legally operate and supply services to buyers. In this context, mutual recognition agreements — especially those focused on professional credentials — represent some of the most impactful policy reforms available to governments. I expand on this later in the report.

Trade costs within the Atlantic region are, on average, higher than those observed interprovincially across Canada as a whole. Nationally, interprovincial trade frictions for goods and services average approximately 9.3 percent, with a range from 5.6 percent to 13.6 percent. For goods alone, the national average is about 1.4 percent, while for services it stands at an estimated 16.8 percent. The higher overall level of interprovincial trade frictions in Atlantic Canada suggests that the potential for reform to positively influence trade volumes — and, by extension, to support underlying economic productivity and growth — is greater here than in most other regions of the country.

There is considerable variation in trade costs across sectors within the Atlantic region. The sectors where trade costs matter most tend to be those that are both trade-intensive and key suppliers of inputs to other industries. Among the most significant trade costs within the region, transportation services stand out, with average tariff-equivalent interprovincial trade costs estimated at approximately 40 percent. Another sector notably affected is architectural, engineering and related services, which face average trade costs of just over 34 percent. While a full enumeration of interprovincial trade costs across the more than 200 sectors for which I provide estimates is beyond the scope of this paper, it is sufficient to say that trade frictions are substantial in many sectors. Of course, many sectors, including those central to the Atlantic region’s economy, encounter relatively low barriers. For example, seafood product preparation and packaging face an average tariff-equivalent internal trade cost of approximately three percent. Breweries in the region, despite drawing significant public attention in discussions of alcohol-related trade barriers, face average internal trade costs of approximately 3.9 percent. These figures suggest that, while alcohol trade barriers are often politically salient, they are not a major economic driver of the broader problem of internal trade frictions.

The Effect of Interprovincial Trade Costs in Atlantic Canada

The second step in the analysis of this paper is to quantify the effect of interprovincial trade costs between the Atlantic provinces, specifically in terms of their impact on economic activity, real GDP, wages and prices in the region. To do this, a comprehensive model of Canada’s economy is employed, based on widely used and well-established methods from the international trade research literature. The model is briefly described in the next section, followed by a discussion in subsequent sections of its implications for the economic effects of trade costs.

Description of the Model

The details of the model, as well as the code enabling replication of its results, are available from recently published work in the Canadian Journal of Economics.[3] A simplified version of that model is used in this paper by excluding government finances and federal-provincial transfers from the analysis. This model is also expanded to include 230 distinct sectors for each province and territory in Canada, with the rest of the world explicitly modelled as well.

While the technical details are not central to this paper, the underlying intuition is relatively straightforward. First, productivity gains in a province from trade liberalization occur because it enables the region to specialize in a narrower range of goods and services and import the rest. This increased specialization leads to productivity improvements, as the goods and services that see reduced or no production post-liberalization tend to be those the province produces less efficiently compared to other regions.

The model simulates changes in purchasing behaviour — both for consumers and for businesses acquiring intermediate inputs — based on an assumed trade elasticity discussed earlier. It also captures the reallocation of employment and output across sectors in response to reduced trade costs, reflecting regional differences in sector-specific productivity. Additionally, the model accounts for worker mobility across provinces. In the model, workers can relocate in response to opportunities for higher incomes or lower living costs prompted by changing trade costs, including moves across Atlantic provinces. How sensitive workers are to changes in living standards across regions is set to correspond to reasonable empirical estimates of the elasticity of interprovincial migration in Canada with respect to real incomes.

Finally, the model features a full set of intersectoral and input-output linkages. Sectoral outputs are used not only for final consumption but also as intermediate inputs in the production of many other goods and services. These linkages are crucial for understanding the broader economic effects of trade costs. As trade barriers fall, input prices decline, which in turn reduces production costs across a range of sectors. The extent of this cascading effect depends on how widely an input is used. Consequently, reductions in interprovincial trade costs have larger economic implications for the Atlantic provinces when they affect upstream goods — that is, those heavily used as inputs rather than consumed directly. These upstream sectors tend to yield the greatest economic benefits from trade liberalization.

It turns out that the aggregate gains from reducing trade costs can be understood as the simple product of two key factors. I refer to this as the marginal cost of internal trade frictions. It is quantified by estimating, first, interprovincial imports as a share of total expenditures and, second, a sector’s centrality in the overall economy. More intuitively, this means that goods that are traded intensively would yield greater gains if trade costs were to decline. This is a straightforward point: when trade is already robust, reducing frictions means fewer resources are wasted overcoming those barriers. The centrality of a sector refers to how important it is as a supplier of intermediate inputs to other sectors across the Canadian economy. This can be calculated relatively easily using publicly available input-output data from Statistics Canada.

With this intuition in mind, I now turn to the quantitative results of the model. These results simulate production and trade under various trade cost scenarios, starting with a uniform one percent reduction as a baseline. This is followed by a scenario reflecting the trade cost reduction observed among the four provinces that formed the New West Partnership. I conclude with estimates of the economic gains from achieving full mutual recognition across the Atlantic region.

Gains from Lower Regional Trade Costs

To understand the sensitivity of provincial economies to changes in interprovincial trade costs within Atlantic Canada, we can begin with a simple exercise: simulating a uniform one percent reduction in trade costs across all sectors and trade pairs within the region. While this is only illustrative, it helps to concretely demonstrate how sensitive various economic outcomes are to changes in trade costs.

| Table 2: Economic Gains from Atlantic Canada Trade Liberalization | |||||

| Region | |||||

| Scenario | NB | NS | PE | NL | Canada |

| Labour Productivity (%) | |||||

| Uniform 1% lower costs | 0.11% | 0.17% | 0.30% | 0.10% | 0.01% |

| Uniform 2.3% lower costs | 0.26% | 0.40% | 0.73% | 0.25% | 0.02% |

| Full mutual recognition | 8.96% | 11.22% | 22.42% | 4.37% | 0.47% |

| Real GDP per Capita ($) | |||||

| Uniform 1% lower costs | $59 | $88 | $169 | $79 | $5 |

| Uniform 2.3% lower costs | $144 | $215 | $410 | $191 | $11 |

| Full mutual recognition | $4,928 | $5,949 | $12,575 | $3,351 | $343 |

| Note: Reports the change in labour productivity (real GDP per worker) and the change in real GDP per capita in dollars for each simulated change in internal trade costs. Dollar values are based on a 2022 baseline.

Source: Author’s calculations. See text for details. |

|||||

Depending on how large one believes the potential liberalizations might be, gains can be scaled from this starting point to approximate broader benefits. In this section, I simulated a one percent uniform economy-wide reduction and, in addition, modelled a one percent reduction separately for goods and services. I also report sector-specific changes in trade costs to highlight the areas that offer particularly large gains for the region — information that can help policymakers allocate their efforts more strategically across sectors (see Table 2).

For the uniform one percent reduction in interprovincial trade costs, I find that wages increase by between 0.1 and 0.3 percent, depending on the province. New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador experience the smaller end of that range, while Prince Edward Island sees the largest increase, with Nova Scotia in the middle at 0.2 percent. In terms of price changes, as discussed previously, lower trade costs can either increase or decrease prices depending on several factors. New Brunswick and Nova Scotia see slight overall price increases — though very modest — at 0.01 and 0.03 percent, respectively. Meanwhile, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador experience price decreases of approximately 0.04 and 0.05 percent, respectively.

Overall, provincial economies increase by between $60 and $170 per capita. New Brunswick sees the smallest per capita gains, while Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador see moderate gains of $88 and $79, respectively. Prince Edward Island stands out, capturing the higher end of the range. These results illustrate that even small changes in interprovincial trade costs within the region can have meaningful effects on the economies of all four provinces. In aggregate, gains in real GDP from a one percent trade cost reduction within Atlantic Canada amount to roughly $200 million per year. Outside the region, it is important to note that it is not only the Atlantic provinces that benefit. While the effects are modest elsewhere, all other provinces in Canada see slight increases in real GDP per worker.

There is also a response in terms of employment allocation across Canada. In reaction to reduced interprovincial trade costs among Atlantic provinces, I estimate that Canadians at the margin may migrate from other regions towards Atlantic Canada. This one percent uniform trade cost reduction results in estimated increases in employment and population ranging from 0.1 to 0.4 percent. New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador fall on the higher end of that range, Nova Scotia in the middle at 0.2 percent, and Prince Edward Island again on the higher end.

Gains from Regional Trade Agreements

Simulating a uniform reduction in interprovincial trade costs of 2.3 percent among the four Atlantic provinces, I find overall national GDP gains of approximately $500 million. These gains are significant, translating into GDP per capita increases of over $140 for New Brunswick, over $190 for Newfoundland and Labrador, nearly $215 for Nova Scotia, and just over $410 for Prince Edward Island (see Table 2). These are substantial gains, reflecting productivity improvements ranging from 0.3 to 0.7 percent, depending on the province. And while the effects are small, all other provinces also see increases in the size of their economies. That trade liberalization within a particular region does not, therefore, simply divert economic activity but instead contributes meaningfully to an improvement in the strength of the overall national economy.

These economic gains are not merely an abstract boost in some statistical measure; they represent real tangible benefits to individuals in the form of higher wages and increased purchasing power. I estimate that wages in the region rise between 0.1 and 0.6 percent, depending on the province. Consumer prices are projected to decrease by 0.1 percent in Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island, while Nova Scotia sees a slight increase of 0.1 percent.

It’s important to note that trade agreements and trade liberalization should not be viewed solely as mechanisms for lowering prices. Liberalization tends to reduce prices on goods for which an economy lacks a comparative advantage, while increasing prices on goods in which it does have one. This benefits producers and, on balance, these gains tend to outweigh the losses borne by consumers of now more expensive goods. Even in Nova Scotia, where the model predicts a 0.08 percent increase in consumer prices, the 0.49 percent increase in wages more than offsets the rise. This results in an estimated 0.4 percent increase in real incomes for residents of the province.

Gains from Full Mutual Recognition

The full and complete elimination of all measured barriers to the trade of goods and services among the four Atlantic provinces yields benefits significantly larger than those estimated under a scenario modelled on the New West Partnership. Estimating these potential gains involves a two-step procedure: first, measuring the prevailing trade frictions between the four economies; and second, simulating the removal of those frictions.

Controlling for geographic factors that naturally influence trade costs—thereby isolating only the policy-relevant scope of liberalization—I estimate that the full removal of measured interprovincial trade barriers would increase real per capita GDP by between 4.4 percent and 22.4 percent. The largest gains would accrue to Prince Edward Island, while the smallest would be seen in Newfoundland and Labrador. Gains in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia are estimated at 11.2 percent and 22.4 percent, respectively. I display these results in Table 2.

These are substantial improvements — equivalent to nearly $3,400 per person annually in Newfoundland and Labrador, and up to $12,600 per person annually on Prince Edward Island. For New Brunswick, the gains amount to about $4,900 per person per year, while in Nova Scotia they are around $5,900. On a national scale, real GDP would increase by $14.7 billion. As with the New West Partnership simulation, all other provinces also benefit, though more modestly — experiencing gains in the range of approximately $10 to $20 per person, depending on the province.

For workers, I estimate wage increases of about 0.4 percent in Newfoundland and Labrador and up to 14 percent on Prince Edward Island, with gains of roughly six percent in New Brunswick and nearly 10 percent in Nova Scotia. Consumers also stand to benefit from lower prices. Estimated overall price declines range from approximately 1.4 percent in Nova Scotia to as much as 6.5 percent on Prince Edward Island, driven largely by enhanced production efficiencies and competition.

Potential Implications for Federal-Provincial Fiscal Transfers

Liberalizing internal trade within the Atlantic provinces can also affect the allocation of federal transfers to provincial governments, particularly those transfers that are sensitive to provincial income levels. Some transfers, of course, are fixed on a per capita basis — such as the Canada Health Transfer and the Canada Social Transfer. Others, like equalization payments, respond to changes in a province’s underlying economic strength. Fiscal capacity, after all, is closely tied to nominal GDP within a province, since changes in the total income earned across the economy directly impact the size of the various tax bases on which these calculations are made. This includes, in particular, personal and corporate income tax bases, as well as the consumption tax base.

This matters because the form in which trade gains materialize has different implications for how these transfers are calculated. For example, if a province unilaterally reduces the cost of importing goods from another, the resulting gains — in terms of real GDP, real income and improved living standards — will come mainly through lower prices, rather than higher wages. Conversely, if gains result from increased demand for a province’s goods — say due to the liberalization undertaken by another province — this would tend to come in the form of higher wages. And since federal transfers are based on nominal rather than real variables, gains that arise through price decreases will not significantly influence transfer calculations. However, gains realized through higher wages may increase a province’s measured fiscal capacity, potentially leading to a reduction in transfers.

Research suggests that measures aimed at boosting the Maritime economies by lowering internal trade costs yield smaller net gains when the impact on fiscal transfers is taken into account. A recent study I undertook with Jennifer Winter,[4] for instance, found that the benefits of a 10 percent reduction in trade costs among the three Maritime provinces are roughly halved once the resulting changes in federal transfers are considered.

A comprehensive examination of this issue is beyond the scope of this paper, but it’s an important consideration. Provincial governments should be mindful of this dynamic, especially given that a substantial portion of their budgets is comprised of federal transfers. To be clear, the overall effect of trade liberalization on the region remains positive and worth pursuing. However, the net benefits — after accounting for changes in transfers — may be smaller than what is otherwise reported here.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

This paper provides a detailed assessment of internal trade costs within Atlantic Canada and evaluates the economic effects of reducing these frictions through regional trade liberalization. Using a well-established model of Canada’s economy, I estimate that even modest reductions in interprovincial trade barriers can yield significant economic benefits for the region — measured in higher wages, lower prices and increased productivity. The gains from trade liberalization are not theoretical. They are grounded in observed data and robust methods and consistent with international and domestic evidence.

Perhaps the most striking result of this analysis is the scale of potential gains from full mutual recognition and removal of internal trade barriers. For all four Atlantic provinces, the benefits are substantial, with Prince Edward Island poised to see the greatest improvements in most cases. These are not merely marginal shifts; they represent meaningful changes in provincial income levels and overall economic strength. Importantly, these gains are not at the expense of other provinces. Rather, they result in net national improvements, with modest benefits extending to the rest of Canada as well.

For policymakers, several implications follow. First, while progress has been made through agreements such as the MOUs between various provinces in recent months, a region-wide approach — similar in spirit and scope to the New West Partnership — could unlock additional economic potential, as demonstrated by other regional trade agreements in Canada. Second, the analysis highlights the importance of services, where trade costs are especially high. Targeting mutual recognition of occupational credentials and harmonizing service regulations should therefore be a priority and seen as more than just a labour mobility issue. Instead, credentials recognition is central to trade liberalization in services.

In short, internal trade reform is a potentially low-cost, high-impact policy lever. While not a solution to all economic, affordability and productivity challenges today, deepening regional trade and mutually recognizing each other’s regulations, credentials and so on can result in substantial economic gains — especially among smaller, closely linked economies like those in Atlantic Canada. With increasing uncertainty internationally, internal trade liberalization offers an interesting opportunity to generate lasting economic benefits for the region.

- † Trevor Tombe is a Professor in the Department of Economics and Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at the School of Public Policy, University of Calgary. Email: ttombe@ucalgary.ca. Phone: 1-403-220-8068. ↑

- Office of the Premier. (April 24, 2025). New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador sign memorandum of understanding to improve trade and labour mobility. Government of New Brunswick. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/premier/news/news_release.2025.04.0157.html ↑

- Tombe, T., and Winter, J. (2021), Fiscal integration with internal trade: Quantifying the effects of federal transfers in Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics 54(2): 522–556. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/caje.12491 ↑

- Tombe, T., and Winter, J. (2021), Fiscal integration with internal trade: Quantifying the effects of federal transfers in Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics 54(2): 522–556. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/caje.12491 ↑