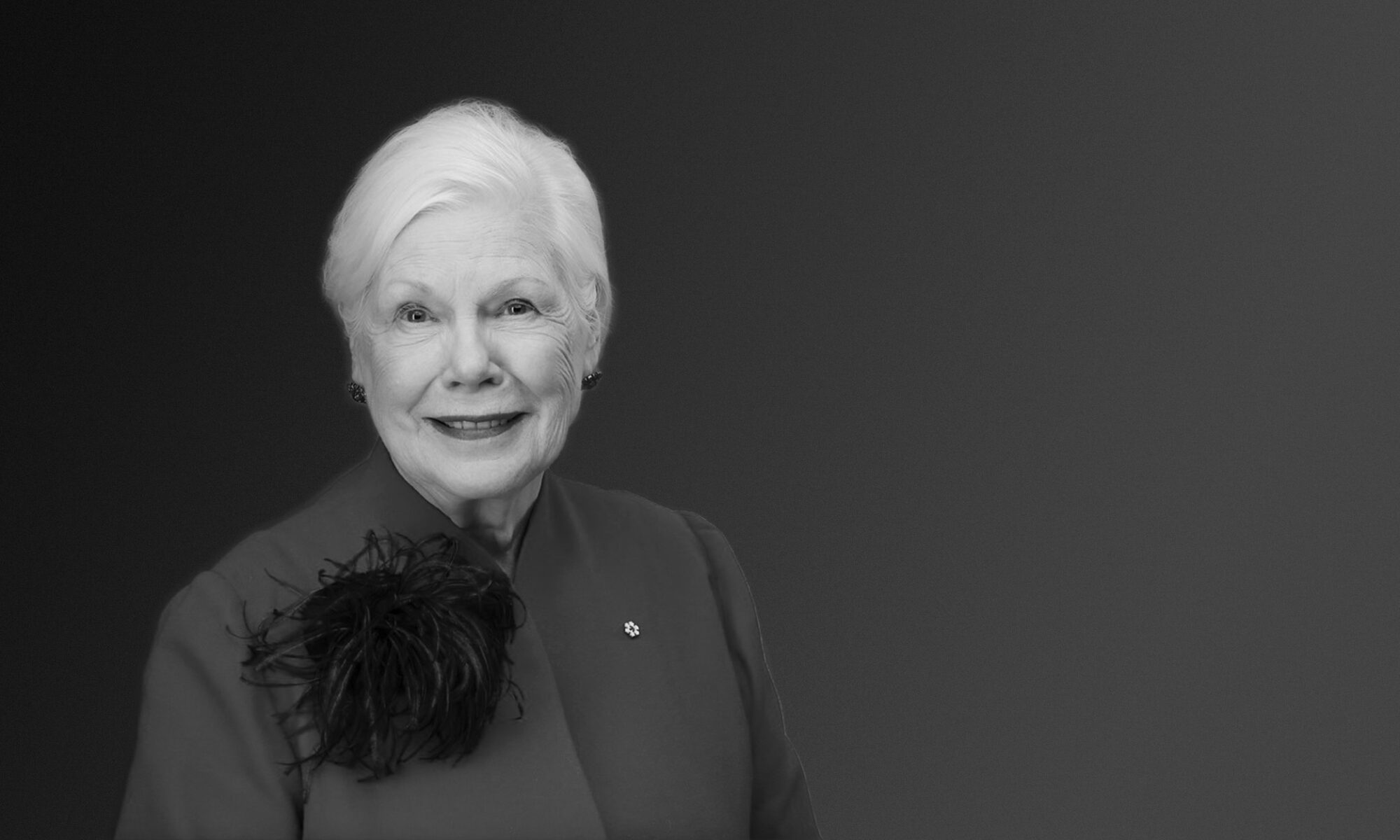

Elizabeth Dowdeswell — 2025 Testimonial Dinner Award Honouree

“I would never have dreamt [I would do] the things that I have done. But when an opportunity arises, I usually say, ‘Is it something worth doing? Am I likely to be working with interesting people? And is it something I know nothing about?’”

Elizabeth Dowdeswell is in transition.

Again.

“I’ve managed many transitions in my life,” says the public servant, whose work has spanned provincial, federal and international borders and transcended traditional disciplinary lines. “My condo looks like an overstuffed locker room,” she offers, explaining that she is sorting through files and contemplating next steps. Despite the upheaval, one thing never wavers. “I knew that I would never retire,” she says, listing a few of the board appointments — University Health Network, Toronto Symphony Orchestra — she has accepted so far.

Much in her life can be traced to her upbringing, she says. Her familiarity with transitions is rooted there, too. Her father was a clergyman who immigrated to Canada with his wife and two children, trading the rolling greenery of Northern Ireland for the yellow plains of Saskatchewan. Dowdeswell is the eldest in a family that expanded to eight children. Every few years, they moved to another small town in Saskatchewan, shifting to new circumstances and friends. Home was the stable centre point, always filled with music, ideas, people and the encouragement of parents for whom higher education was “a given” for all their children.

Curiosity drives her forward, she explains. Curiosity about what? “Everything, everything,” she responds, peering into the Zoom camera with a smile. Eclectic choices have been the hallmark of her career. “When I left from field to field, it was because someone would come to me and say, ‘There’s a really interesting job opening up. Why don’t you think about it?’ It’s all been pure serendipity.”

Elizabeth Dowdeswell, who holds 11 honorary doctorates and is an officer of the Order of Canada, started off as a high school teacher and guidance counsellor in Saskatchewan after graduating with an applied science degree in home economics. But the teacher was soon schooling herself in the issues of her community, working across provincial government departments on education, youth and culture files. Along the way, she added a master’s degree in behavioural science.

By the 1980s, she was involved in the federal public service, at one point appointed assistant deputy minister at Environment Canada and negotiating on the Framework Convention on Climate Change, while in the same period leading inquiries into Canada’s unemployment benefits program and federal water policy.

The next decade saw Elizabeth Dowdeswell selected to lead the UN Environment Programme in Nairobi, Kenya. “Once you work internationally, it changes your whole perspective on the world. You learn about the commonalities of views and also the distinct differences.” The issues tackled were complex, such as how to promote sustainability while simultaneously supporting economic prosperity and social cohesion.

“I would never have dreamt [I would do] the things that I have done,” she says. “But when an opportunity arises, I usually say, ‘Is it something worth doing? Am I likely to be working with interesting people? And is it something I know nothing about?’”

It’s a matter of being a risk taker, she says, and having the confidence that with hard work, empathy and active listening, she could have an impact. “I’ve worked in and around government most of my working life. Much of my work was in a consultative field. [But] I don’t use the word consultation. … It has such baggage associated with it. The word I use is engagement because that implies that there’s a give and take; that there’s an opportunity for people to be part of the conversation.

“Much of (the work) relates to being the bridge builder or the interpreter between worlds of science and technology and the world of public policy because they don’t talk the same language,” she says of her approach, which gave her the confidence to tackle new sectors. “I’ve always understood public policy problems as requiring a systemic and holistic view.”

When working on high-level nuclear waste, for example, Elizabeth Dowdeswell created a series of dialogues across the country. “There were board members who said, ‘What is this woman doing? She’s talking to ordinary people about something so complex.’ I had to suggest to them that I wasn’t about to try and turn citizens into experts on nuclear waste. What I was trying to do was to help us understand what really mattered to people. What are their values? Because if we understood that, we could then find common cause, and then start to look at solutions to what the real problem was. … For the citizens’ views to be heard is really very important. It’s about integrity. It’s about doing what you say you’re going to do.”

“Well-functioning democracies require strong institutions, civil discourse, safe spaces for genuine conversation and respect for each other. We are vulnerable in a fast-paced world of technologies and social media and short-term thinking. The work is far from over.”

With so many chapters to a career, her 2014 appointment as lieutenant-governor of Ontario was a happy culmination of her interests and skills. “(The role) is absolutely non-prescriptive,” she says. Aside from constitutional duties and “honouring and serving the community, the wonderful platform allowed me to really convene people.”

Having served as president and CEO of the Council of Canadian Academies, which involved gathering expert panels, Elizabeth Dowdeswell had fingers in a lot of scientific pies. In the “intimacy” of Queen’s Park — a space “that creates a different conversation altogether” — she could be the host, bringing together leading scientific authors along with activists, policymakers and citizens to discuss a range of topics from a celebration of culture to climate change concerns. Some of the most important conversations in her provincial salon centred around lessons learned from a global pandemic; the recognition of society’s inequalities; our interdependence; and the need for evidence-based policies, she says.

During the pandemic, she cold-called more than 200 leaders across Ontario, simply to ask how they were. “People don’t think to ask leaders how they are. They assume they’re somewhat invincible.” (Ontario Premier Doug Ford has described Dowdeswell as “like my personal therapist.”) Among other initiatives during the pandemic, she organized under-employed musicians to perform on Zoom for residents of long-term care facilities.

She saw herself as the “storyteller-in-chief,” encouraging Ontarians, including new immigrants and Syrian refugees, to describe their lives and experiences. She would explain constitutional democracy and the role as the sovereign’s representative. “I wanted to tell you that you belong here,” she recalls telling them.

With over 5,000 official engagements and visits to 124 ridings in Ontario, her time as lieutenant-governor deepened her understanding and appreciation of democracy. “It’s so much more than a vote. It’s actually about how do you negotiate the ground rules for how we’re going to live together. … It’s not just the big decisions that are taken by federal and provincial governments.

“Well-functioning democracies require strong institutions, civil discourse, safe spaces for genuine conversation and respect for each other. We are vulnerable in a fast-paced world of technologies and social media and short-term thinking. The work is far from over.”

Expect to hear more from Dowdeswell about her non-retirement.