Legitimacy in Reconciliation: A Path Forward

Government of Canada

Centre for Public Impact

First Nations University of Canada

Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy

The Public Policy Forum acknowledges and thanks the work of the team and volunteers who made this project possible: Naushin Ahmed, Danielle Belanger, Allan Clarke, Michael Collins, Ron Crowe, Moses Gordon, Rebecca Hunt, Denise Kaiswatum, Bob Kayseas, Jaimee Lavallee, Nickita Longman, Joanne Lufty, Linsay Martens, Patty MacCarthy, Kathy McNutt, Sharon Moberly, Rhonda Moore, Nadene Perry, Husvini Poolay, Carl Neustaedter, Jonathan Perron-Clow, Andre Petheram, Nadine Smith and Ledy Tredre.

Foreword

By Moses Gordon and Nickita Longman

In light of recent events in the Canadian public sphere, the Public Policy Forum’s project on government legitimacy in the context of truth and reconciliation could not have occurred at a more opportune moment. This statement is made in relation to the criminal justice system, which is now facing a serious crisis of legitimacy following the highly publicized trials of Gerald Stanley and Raymond Cormier. Fresh off the heels of the year-long celebration of Canada’s 150th, their subsequent acquittal in two separate homicides of Indigenous youth in the prairies – those of Colten Boushie and Tina Fontaine – have sparked a wave of uproar and protests by Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike across the country.

In the case of Colten Boushie, Canadians witnessed the public mishandling from the very start of the case of the killing of an Indigenous youth from Red Pheasant First Nation. The public was horrified to hear that members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police ambushed the residence of Boushie’s mother, Debbie Baptiste, and falsely accused her of inebriation before ultimately delivering the news of her deceased son without any regard to the sensitive nature of the situation. When the case came to trial, Canadians learned that an all-white jury had been selected in a northern district with a population that is 28 to 96 percent Indigenous. It was later revealed that all Indigenous-looking jury candidates were called to stand, challenged and subsequently excluded by Stanley’s defense team. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this jury selection shifted the expectations of many that the case would result in a conviction for second degree murder to a more lenient manslaughter conviction. But Stanley’s subsequent acquittal by this jury defied all public expectations, which were that a manslaughter conviction was thought to be the bare minimum outcome. The startling acquittal of Stanley initiated a call of support from local farmers and white supporters alike that raised over $200,000 in just two days to cover his legal fees. From the initial investigation to the court case and the resulting acquittal, many are still processing the disappointing inadequacies and institutional racism displayed by the justice system in respect to cases of Indigenous lives.

Tina Fontaine was a victim of the Canadian state’s public institutions in her own right. Originally from the Sagkeeng First Nation in Manitoba, Fontaine moved to Winnipeg to reconnect with her birth mother at the age of 15. After being reported missing in July 2014, Fontaine was a passenger in a vehicle driving erratically that was pulled over by police. The driver was taken into custody and, despite taking her name down, officers let Fontaine go. A few hours after her interaction with the police, Fontaine was found unconscious in the streets of Winnipeg and taken to a nearby hospital. Hospital staff identified Fontaine and released her into the care of Child and Family Services. That was the last documented run-in Fontaine had with the state before her body was found in August. Eyewitnesses and sources close to Fontaine testified her relationship with Raymond Cormier involved drug use and predatory behaviour. In a month, Fontaine had recorded encounters with health care workers, Child and Family Service workers and law enforcement officials all before her body, wrapped in a duvet blanket and weighted down with rocks, was pulled from the Red River. Cormier was found not guilty in the death of Tina Fontaine in February 2018. The circumstances leading to her death shed light on the dismissiveness experienced by Indigenous people, and youth in particular, at the hands of the country’s public institutions.

The outcomes of these highly publicized trials has depleted any faith Indigenous communities had in the judicial system. It is widely acknowledged that the Canadian justice system has been utilized in the past as a tool to impose colonial policies onto First Nation communities; policies that have been expressed most clearly in the federal piece of legislation known as the Indian Act. But these events extend beyond a mere historical footnote, as the Indian Act itself still exists today in a form that continually denies First Nations self-governance and self-determination. This lends credence to those who see the Canadian justice system as an institution blanketed with systemic racism despite the rhetoric put forward by Canada’s leaders. And when it is broadcast publicly that the killings of young Indigenous people – including youth such as Colten Boushie and Tina Fontaine – can take place without serious and just repercussions, we are then sending the message that Indigenous youth are solely responsible for their own violent deaths in this country, which, in turn, diminishes Indigenous livelihood and self-worth. In the case of the ruling regarding Tina Fontaine, such an outcome can only further amplify a pre-existing history of endemic gender-based violence as experienced by Indigenous women – Canada’s most marginalized social group – across the country. This situation will result in a seriously diminishing loss of faith in the justice system that will then begin seeping into other domains of our public institutions, which are themselves already viewed by Indigenous peoples as having questionable legitimate status given Canada’s foundation as a colonial state.

In protests, rallies and marches throughout the country, it has become apparent that Indigenous movements are questioning the government’s commitment to reconciliation in ways unlike anything that has been witnessed before. The common angst can be seen in various levels from grassroots organizing to academic spaces, all with a similar question at its core: How can this country attempt to even approach such a concept without justice for Indigenous lives? In an era where truth and reconciliation have been upheld as a guiding principle for re-igniting a nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous communities, such a situation cannot result in a positive or progressive conclusion. Indeed, the lack of public faith and trust in governmental institutions held by Indigenous peoples in Canada, due to both historic circumstances and recent events, raises a serious red flag. How can a government function when the very legitimacy of its public institutions, which serve as a foundation for the maintenance of this country’s democratic culture, are in such a severe state of ongoing crisis?

The aftermath of the Stanley and Cormier trials has pinned Canada into a corner, as if to suggest that we cannot achieve reconciliation if there is no justice. And as of recently, we have not seen such a thing. However, there is still an opportunity for the government to make change. This damaging situation has highlighted the deficiencies of the Canadian justice system by visibly unmasking the systemic racism embedded so deeply within its structure. In so doing, we as a country have been presented with a possibility for change: the aftermath of these cases presents the federal government with an opportunity to publicly take action and stand by its commitment to truth and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. Before change can be initiated, however, it is necessary that this country recognizes the truth – as well as the present-day realities – of its long and complicated history with colonialism.

Moses Gordon is from the George Gordon First Nation. He is employed in research at the First Nations University of Canada with the School of Business and Public Administration. He is also a master’s student with the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Regina. Moses currently serves on the board of directors for George Gordon Developments Ltd. – the community-owned economic development corporation of his First Nation – as well as various committees at the University of Regina.

Nickita Longman is from the George Gordon First Nation on Treaty 4 Territory and has grown up in Regina. Nickita graduated from the First Nations University of Canada with a BA in English in 2013. She is the Indigenous Program Coordinator for the Saskatchewan Writers’ Guild, a freelance writer and a Briarpatch board member.

Executive Summary

In November 2017, the Public Policy Forum brought together a group of almost 30 Indigenous students, faculty, guests and facilitators to consider questions about the legitimacy of government to meet the demands and expectations of its citizenry. The basis for this discussion on legitimacy was the commitment of the Government of Canada, under the leadership of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, to reconciliation and a renewed relationship with Indigenous Peoples, based on the recognition of rights, respect, co-operation, and partnership.

Participants were asked to consider:

- To what extent does the government have the legitimacy to act on its commitment to a renewed relationship with Indigenous Peoples?

- What is legitimacy, in the context of this commitment?

- How can the government acquire legitimacy in the eyes of those who are directly affected by this process?

- What does reconciliation and a renewed relationship look like?

These questions and others helped shape the discussion.

Two short presentations on the government’s process to date and the concept of legitimacy of government laid the groundwork for six hours of discussion about many of the issues where these two concepts intersect. Young people from across the Saskatchewan, different Indigenous heritage groups, different walks of life and different disciplines — from early childhood education to law to business — worked together to give constructive voice to each other’s ideas.

The tone of the day was positive, constructive and forward-thinking. The quality of discussion and ideas that participants offered was nothing short of inspiring. Participants gave each other hope for change; change that participants could visualize in their own lifetimes.

Since the Nov. 29 unconference (see Methodology), a number of events have transpired:

- Recent verdicts that found two white men — Gerald Stanley and Raymond Cormier — not guilty in the deaths of two young First Nations people — Colten Boushie and Tina Fontaine — have further, and dramatically, eroded confidence that Indigenous Peoples can be treated fairly in Canada’s criminal justice system.

- The Government of Canada released a new federal budget that highlighted efforts to promote reconciliation, including new investments for housing, child and family services, education, health care and access to clean drinking water, and to support capacity-building and advance self-determination and self-government.

- The prime minister made a statement in the House of Commons that the Government of Canada, in partnership with Indigenous Peoples, will develop a recognition and implementation of rights framework. The framework is intended to include new legislation and policy that will make the recognition and implementation of rights the basis for all relations between Indigenous Peoples and the federal government going forward.

It is uncertain what impact these events would have made on the discussion in November. But the impact of the verdicts in the Stanley and Cormier cases have seriously undermined people’s — both Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike — confidence in the criminal justice system, and in an entire system that seems to have tragically left people behind.

Even ministers of the Crown recognized the challenge. The minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs, Carolyn Bennett, stated: “Tina’s is a tragic story that demonstrates the failures of all the systems for Indigenous children and youth on every level.” The minister of Justice and Attorney General, Jody Wilson-Raybould, tweeted in the aftermath of the Gerald Stanley decision: “As a country we can and must do better – I am committed to working everyday [sic] to ensure justice for all Canadians.”

This report strives to remain true to the spirit of the Nov. 29 unconference. The recommendations are unchanged from their original format. But, in light of recent events, we are reminded that the struggle to achieve reconciliation in Canada will not be an easy one.

Here are six recommendations to demonstrate action, accountability and legitimacy in the process to achieve reconciliation:

- Adopt the 94 calls to action

The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission documents the history of colonization in Canada and the residential school system, and provides practical calls to action in the areas of education, law, health, language, culture, and other areas that would serve to advance efforts to promote reconciliation. The Government of Canada should work with the provinces, territories and other relevant stakeholders to:

- Take immediate steps to implement the 94 calls to action; and,

- Document progress of the implementation on all relevant Government of Canada websites, in plain language.

- Stop the adversarial approach

It’s time for the Crown to stop fighting Indigenous Peoples on the recognition of their Aboriginal rights. These rights are already protected by Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The Government of Canada should:

- Cease the litigious and adversarial approach to Aboriginal rights by placing a moratorium on legal challenges to the expression of Aboriginal rights; and,

- Engage in nation-to-nation, Inuit-to-Canada and government-to-government dialogue and negotiation to find mutually agreeable resolution where there are disputes.

In addition, the Department of Justice should move to make legal opinions publicly available in plain language.

- Redefine the balance of power

Canada must share decision-making power with Indigenous Peoples. Today, the Government of Canada wields a disproportionate amount of control over the pace and scale of change. Reconciliation is a two-way street. As the party who committed the injustice, it is time for the Government of Canada and all non-Indigenous citizens to recognize the role each one has played — directly or indirectly — in the systemic repression of Indigenous Peoples. Collectively, all Canadians have a responsibility to make amends and take concrete steps to redress the harm that systemic repression of Indigenous Peoples has caused.

- Canada needs to be complicit

Participants of the unconference, including those who worked for the Government of Canada, expressed disappointment that there is a strong prevailing sense that the government and its representatives lack empathy for making things right. Every federal department should develop a reconciliation action plan that clearly identifies how each department will support reconciliation in Canada. These action plans should be tied to each department’s strategic plan and include practical actions that will contribute to reconciliation. Departmental plans will include measures to demonstrate progress and accountability that will have direct implications on departmental budgets.

- Actions speak louder than words

Many participants expressed dismay at how little has been done and how little has changed, despite the priority the government has placed on the Indigenous agenda. Yet there are programs and procedures that can be amended to create real, timely change. Unconference participants recommend that the Government of Canada, working with provinces and territories, take immediate action to correct that which can be done in an expedient manner to reduce the economic and social barriers facing Indigenous Peoples. For example, while investments in housing and infrastructure have been described by the government as “historic,” they will not significantly address the shortfall if the government continues to fund housing and infrastructure in the same “pay-as-you-go” manner. It is time to design a plan to finance a housing solution, not just homes.

- Get our own house in order

A number of participants also reflected on governance structures within Indigenous communities, and the lack of confidence in them. In many cases, governance systems are not chosen by the community, but are forced upon them through the Indian Act. The Government of Canada and Indigenous Peoples should work together to re-establish culturally relevant governance structures — rooted in traditional Indigenous cultural values — to rebuild these communities

Collectively, these recommendations offer tangible means by which the Government of Canada, among others, can enable a legitimate reconciliation process.

Introduction

In August 2017, the Centre for Public Impact approached the Public Policy Forum (PPF) to be a part of a global project that explores What is legitimacy? How is it achieved and preserved? How does it manifest in different parts of the world? The study — with partners in Singapore, Brussels, Mexico, Malaysia, India and the U.K. — would seek to answer these questions by examining legitimacy through the lens of a current challenge facing each respective national or supranational government.

The outcome would offer a two-fold result. First, findings of each case study would provide insights for the respective governments as to how they can build and nurture legitimacy with their citizenry in an area of national importance. Second, the findings from each country would contribute to the creation of a framework for legitimacy; a theoretical tool to inform the work of any government, at any level. This framework would be a living document, reflecting the ongoing work of the Centre for Public Impact (CPI), which would continue to lead this global project and involve the perspectives of people around the world. (For more information about CPI’s global legitimacy project, visit: https://webportalapp.com/portal/ppf-review.)

In Canada, PPF chose to explore legitimacy in the context of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In keeping with the global approach to this study, PPF targeted Indigenous Peoples under the age of 30 for the engagement process, bringing them together to discuss the following questions:

- Does the Government of Canada have the legitimacy to deliver on its commitment to Indigenous Peoples?

- What actions could the Government of Canada take to enhance legitimacy of its work and promote transparency and trust with Indigenous communities?

- What means or processes could the Government of Canada establish to strengthen transparency and trust with Indigenous Peoples? And,

- How can the Government of Canada better engage all Indigenous Peoples — in particular, emerging leaders — in a meaningful dialogue on legitimacy and reconciliation?

Methodology

On Nov. 29, the First Nations University of Canada and the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy hosted the PPF and 21 young Indigenous Peoples for an unconference to explore the themes of legitimacy, government and reconciliation.

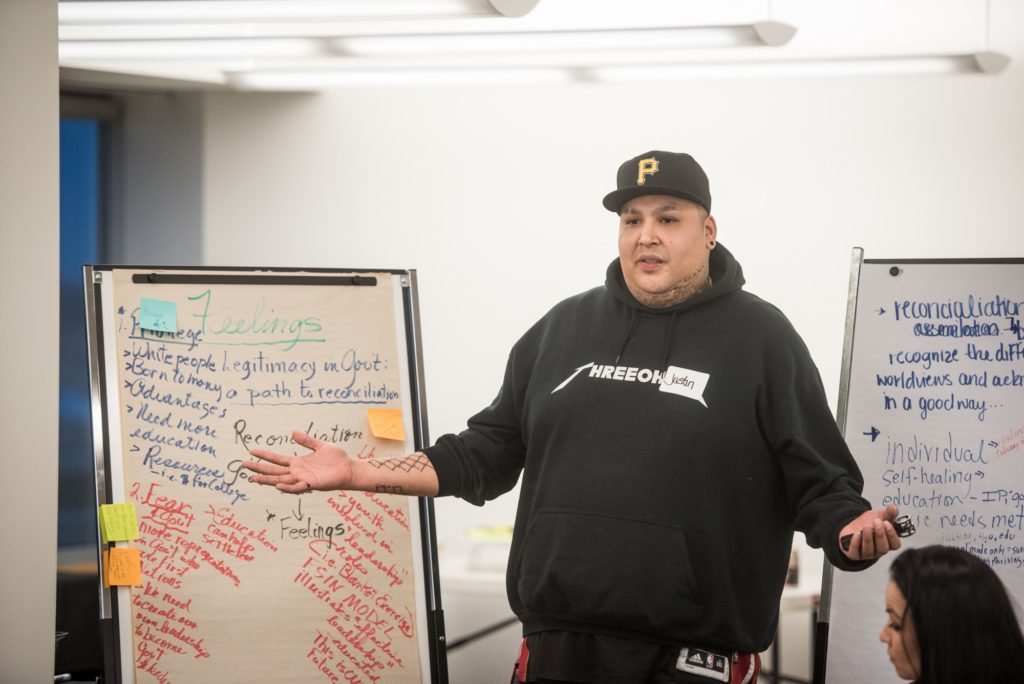

Organizers intentionally chose the unconference format for this event. In an unconference, participants are provided with some context-setting information; they then work as a group to identify the discussion topics for their time together. In doing so, participants have the authority to determine the topics that are most relevant and important for them. This model matched the goal for the day: to identify what parts of the legitimacy and reconciliation conversations are of utmost importance for young Indigenous Peoples.

To ensure that all participants had the same information with which to engage in conversation, the unconference began with two short presentations and a group discussion. After an elder opened the unconference with a blessing, Allan Clarke, senior associate, Public Policy Forum, presented an overview of the Truth and Reconciliation Process, and Nadine Smith, global director of marketing and communications, at CPI defined and explored this idea of legitimacy for unconference participants. Their presentations were followed by a response from Ron Crowe, executive-in-residence at the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy, and Dr. Jaime Lavallee, director of Indigenous governance, law & policy at the File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council. The themes of their response was why all of this matters anyway.

Following the presentations and responses, participants identified the topics that were of utmost importance to them. There were many:

- credibility and authenticity;

- the Indian Act;

- democracy and self-determination;

- state protection;

- Indigenous self-government;

- is the Assembly of First Nations legitimate;

- nation building;

- the Kelowna Accord and how it became about building relationships;

- building equal partnerships among leaders;

- practical sovereignty;

- breaking down the colonized view on policy;

- treaty relations with the Crown;

- educating the governments in Canada about Indigenous ways;

- racism;

- feelings; and

- cultural revitalization.

These topics were organized into four broad themes: each theme became the focus of a small group discussion. Participants met in these small groups for two hours, and then came back to the larger group and shared all that they had talked about. The following sections explore dominant themes of the small and large group discussions.

Setting the Stage

Reconciliation

‘No relationship is more important to me and to Canada than the one with Indigenous Peoples. It is time for a renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous Peoples, based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation and partnership.’ – Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada

Indigenous Peoples have a special constitutional relationship with the Crown. This relationship, including existing Aboriginal and treaty rights, is recognized and affirmed in Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, and holds the promise that Indigenous nations will become partners in Confederation on the basis of a fair and just reconciliation between Indigenous Peoples and the Crown.

The Government of Canada has stated its commitment to achieving reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples through a renewed, nation-to-nation, government-to-government, and Inuit-Crown relationship based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation, and partnership as the foundation for transformative change.

Despite this promise — and Canada is one of the few countries that have recognized Indigenous rights in its Constitution — Indigenous Peoples have been victims of the deliberate denial of these rights, systemic racism, paternalism, incompetent administration, a lack of adequate resources and — according to some — cultural genocide.

Canada has one of the highest standards of living in the world. According to recent figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canada has the highest rate of post-secondary education among its member states, Canadians have a higher than average life expectancy, our annual disposable income far exceeds the OECD average, and we have the 3rd highest level of citizens reporting to be in good health.

Yet Indigenous Peoples lag well behind the Canadian average in terms of educational achievement, workforce participation and income, and well ahead of the Canadian average in terms of incarceration and recidivism, diabetes and suicide, to name only a few indicators. And, in many cases, Indigenous Peoples lack the basic services that most other Canadians take for granted: adequate housing, access to potable water, good schools, decent health services, food security and public safety.

Many have heartedly applauded the prime minister’s commitment to a renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous Peoples, based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation, and partnerships. But after two years into its mandate, some have argued that the Liberal government has failed to live up to the ambition of the prime minister’s commitment.

Principles respecting the Government of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous Peoples

Having just marked 150 years of Confederation, it is time to ask what we want the next 150 years to look like and the role First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation will have in building a stronger Canada. Implementing this commitment is an important undertaking that requires a whole-of-government approach. To that end, a Working Group of Ministers, announced by the prime minister in February 2017, has been established to review laws, policies and operational practices that impact Indigenous Peoples and their rights and interests.

The working group is chaired by Jody Wilson-Raybould, minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, and includes the ministers of: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs; Indigenous Services; Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard; Natural Resources; Families, Children and Social Development; and, Health.

The working group is taking a principled approach to the review of laws and policies to ensure that the Crown is meeting its constitutional obligations with respect to Aboriginal and treaty rights; adhering to international human rights standards, including the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP); and supporting the implementation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action.

This review of laws and policies will be guided by Principles Respecting the Government of Canada’s Relationship with Indigenous Peoples. According to the Government of Canada, these principles are rooted in Section 35, guided by the UN Declaration, and informed by the 1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action. In addition, they are intended to reflect a commitment to good faith, the rule of law, democracy, equality, non-discrimination, and respect for human rights. The principles will guide the work required to fulfill the government’s commitment to renewed nation-to-nation, government-to-government, and Inuit-Crown relationships.

Since its election in 2015, the government has pointed to a number of actions to achieve its commitment.

First, by taking steps to address important social, economic and social needs:

- It has eliminated the two-per-cent funding gap, which had been in place for over 20 years;

- It has committed $11.8 billion over five years to support Indigenous communities, including for housing and infrastructure — resulting, according to the government, in 29 fewer boil water advisories, the building or renovation of 6,400 homes, and 135 projects to build or refurbish schools;

- It has launched the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

Second, by taking steps to establish foundations necessary for a renewed relationship and a transformation of Canada’s laws, policies and operational practices, the Government of Canada:

- Endorsed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples;

- Is completing a review of environmental regulatory processes;

- Created a Working Group of Ministers and released the Principles Respecting the Government of Canada’s Relationship with Indigenous Peoples;

- Placed a moratorium on the claw-back of own-source revenue of self-governing Indigenous governments;

- Divided Indigenous and Northern Affairs to create two new ministries of Indigenous Services and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs; and,

- Concluded sectoral agreements, including the Anishinabek Nation Education Agreement and the Manitoba First Nations School System.

There are many who feel the story of Canadian inclusion, which features largely in our country’s narrative, has not only deliberately and malevolently excluded Indigenous Peoples from sharing in Canada’s prosperity, but also sought to extinguish the very existence of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Arguably, Canada’s biggest public policy challenge is achieving reconciliation in our country, while incorporating the recognition of Aboriginal rights and title and addressing the shameful socio-economic conditions facing Canada’s Indigenous Peoples.

Reconciliation between Canada and Indigenous Peoples does not seem possible without putting the past, the present and the future into a context in which concrete actions are taken that help repair, improve and rebuild the relationship. Building the trust and legitimacy required to take these actions may be this government’s greatest challenge.

The Concept of Legitimacy

(The following is an excerpt from a speech delivered by Nadine Smith at the Nov. 29 unconference.)

What is legitimacy, and why is it important? This is a tough question. Talking about this at all is not easy for anyone. But governments owe it to their citizens to have [legitimacy] right now and without delay.

Many philosophers have tried to explain legitimacy, yet in the 21stcentury we still do not have the words we need to adequately describe the times we live in and the expectations citizens have on government and government on citizens. Globally, are we entering a crisis of legitimacy? The lack of language that enables us to express our true feelings may be part of the problem today. Problems and deep feelings can get misunderstood, misrepresented in government and miscommunicated.

In history, the most common solution is war or chaos as a way out of a feeling of disconnectedness. We enter unchartered territory finding a way to correct imbalances of wealth and power as the gap between rich and poor widens and people feel the strain. Legitimacy, and finding it, therefore matters.

As part of this global project to define legitimacy, the Centre for Public Impact (CPI) looked at traditional concepts such as values, fairness, transparency and democracy and asked people: Are these still relevant? The result demonstrated there is less usefulness in these age-old ways of talking about it. Who decides what is and is not fair? The majority may say, ‘Go with the majority’, but if you are a minority, you will never be a majority. How is that fair? Young people today certainly feel this and say to us they care less and less about democracy. They care more for adequate provision of services to all, equity, housing, health and jobs than they do about their vote in an election. Should we be worried about that?

Legitimacy is essentially about how people feel about government. To date, governments have been focused on what they do and having a record of delivery in order to gain trust and votes. Conversations happen ad hoc and around election time. It is no longer enough.

CPI is moving the conversation to the practical and not looking too deeply at normative definition of legitimacy — i.e., is this a legitimate government? CPI focuses on the empirical definition of legitimacy to understand how people are reacting to government. Through real-life stories, CPI analyses the feelings of citizens and their ability to make sense of world events and movements that have not yet been explained through traditional concepts. CPI defined legitimacy, therefore, as the broad reservoir of support that a government needs to be able to achieve outcomes for people.

Feelings are not the business of government on a day-to-day basis, unlike policy or delivery. Governments need to be helped in making sure they not only listen but act on what they hear. To be trusted to do this will require some bold moves, like hearing from those they otherwise might not [hear from] and really listening.

Feelings are a tricky issue. Government institutions don’t do feelings. Therefore, the question becomes not what is a legitimate government, but whether individuals feel and believe the government is legitimate.

Embracing this concept transforms legitimacy into a mushy and tough topic to tackle. It’s not scientific because humans do not have programmed responses, though governments may wish we did. In addition, there are cultural lenses through which we view legitimacy that differ from nation to nation, city to city, group to group. There is no single universal definition of legitimacy.

Legitimacy is also an evolving, fragile state. Governments cannot ignore their legitimacy when times are busy, outcomes look good and opinion polls look favourable. Indeed, governments around the world are finally seeing and fearing they may become irrelevant altogether if they don’t address legitimacy every day — at last! Long gone are days when we accept government and all it does until election time.

So, what’s changed?

Firstly, we are now a more informed citizenry, especially about our rights. Secondly — through the advent of social media — we have more tools at our disposal than ever before to discuss how we feel. Thirdly, citizens no longer want to be treated as customers of public services. We are citizens. Citizens are a part of society who have a stake in their communities and the country. When those in government get laws, policies or regulations wrong, citizens might be understanding if the error is made with consent, but not when the error results from arrogance. When this happens, governments will have to work harder to gain traction on subsequent issues — a place where governments often get into trouble. At a global level, governments keep repeating this mistake over and over again.

As a result, citizens are asking tougher and tougher questions about who government is, and who are the people that make up a government? Citizens have begun to realize what their power over government is, and how it may be applied formally to exert power. Indeed, young people are realising they have this power, too. They have demonstrated a more nuanced understanding of the power of digital platforms. Younger generations also don’t fear the instability of change; in fact, they were born into it. Are young people a whole new threat? No. Young people want to change their world and governments should help them do this, but governments will require new skills and patience that they have not always [needed to] have. Could this new generation of digitally-savvy individuals who revel in instability lead to a whole new way of doing government? This is something CPI will continue to investigate.

Government of the future with you(th) in mind

Legitimacy isn’t an add-on or nice thing to do or a problem for government press officers or marketing teams.

Can governments — as they look and feel now — make legitimacy a key function of government? Do they know how to have difficult conversations on issues they don’t even know the answers to? It takes a brave government to admit it doesn’t know, and the government machine isn’t geared up for that. How you feel about government — whether you think it is fair, or compassionate, or empathetic, these are questions of legitimacy.

What we Heard

Our participants organized themselves into four groups around the themes of feelings, reconciliation, governance vs. government, and legitimacy. The following sections are written in the first person, plural, to capture the voices of the young people who delivered these ideas.

Reconciliation

True reconciliation will mean addressing many, many things that are wrong with how Indigenous Peoples live in Canada:

- Giving more access to education;

- Not taking all our children away and putting them in foster care;

- Enabling food sovereignty;

- Recognizing Indigenous veterans;

- Addressing intergenerational trauma as a result of the residential school system; and,

- Revitalizing lost culture and preserving traditions.

What is a Nation?

We do not aspire to a nation-to-nation relationship. Indigenous Peoples are not one big nation. We do not regard a nation as a population living in a space defined by lines on a map. We are many nations. We are 683 nations, living all over the place, and each with a distinct way of living.

How did we go from treaties with different areas to one nation? If we could reimagine those treaties today, how would we do it? This is an important place to start.

It is the western way of thinking — imposed upon us — that created the idea we are all one nation. Presenting ourselves as one nation is not a legitimate representation of who we are or our true governance system. The chief of the Assembly of First Nations does not speak for all First Nations. We should be building nations within the nation. Only in this way can we have legitimacy to speak through one person. For us, reconciliation means understanding how we came to be who we are today. Reconciliation is not about reinventing ourselves. Reconciliation will be about enabling us to return to the way we used to be. The “way we used to be” is a highly localized concept. To the unconference participants, for example, this means a matriarchal society with oral storytelling traditions, practising restorative justice, respecting our traditional ceremonies and traditional lands, with gender equality and a self-determining economy, and less reliant on non-renewable resources.

Preserve and Adapt

We want to preserve and adapt. It is important to respect the ways of the previous generations and the decisions they made. It is important to think about the generations that will come after us, and to work with their best interest in mind, because we are stewards of the earth and its resources. We are part of a continuum that began long before us and will continue long after we are gone.

Talking about change can be uncomfortable for us. The philosophy of our whole being as Indigenous Peoples is to keep being who we are and have been. Yet, there are decisions our ancestors made with which we do not agree. To question the actions of our ancestors is not the way we were taught. This is a sensitive subject for us.

There is a divide among our own communities about the treaty system. Some people believe treaties made things better, others believe they made things worse. Some believe treaties were designed to get “rid of Indians”.

Communication within Indigenous communities can be challenging. These feelings can be lost in translation, if we are able to vocalize them. How do we confront our families and ancestors with these feelings without undoing our teachings?

The Future

A question for us: As Indigenous communities, what do we have that defines us if we don’t have a society of our own? We undermine ourselves — and what we could be — by not asking this question.

We are people of the land. But we know that a successful future will require money. Our incomes from the federal government haven’t increased since the 1980s. Our families now live with pressing social and health issues. We need real revenue to address these problems. We need real relationships with the Canadian government to overcome the problems we face, to enable us to assert ourselves, to take care of ourselves, and to realize our full potential.

There was a time — under Queen Victoria — when our nations had real relationships with other governments. We need to rebuild those relationships, but without any assumptions. A legitimate future is not one where Indigenous Peoples continue to live in a society based on Western values and governed by a Westminster model. Indigenous Peoples come from matriarchal, nomadic societies. Their governance system is not based in the Westminster model. For legitimate reconciliation, these two governance systems will have to co-exist, or a new model will need to be created where the values of both co-exist.

But first the Government of Canada needs to build trust with us. We are not yet ready to talk about negotiating with the Government of Canada because we do not trust that government to uphold promises, let alone trust it with our future. The Government of Canada must start changing things, not just saying things. It’s time to change the government system. The current system is set up to prevent relationships happening. We need more partnerships with government. We need more of our own people in government to make change happen.

Acknowledge Feelings and Promote Education

Some Indigenous Peoples grow up ashamed to be such. We wish we were different. It is only through learning about ourselves and our culture that we develop pride in who we are. Does anyone feel like us? Do they know we exist? We see white people and the privilege they are born with. For some, it seems easier to be white.

Everyone in Canada should know the history of Indigenous Peoples. Everyone should learn about how Indigenous Peoples have been treated since colonization. Through education we can enable change for our own communities and for the rest of Canada.

We need more Indigenous teachings — in public school systems and post-secondary school systems — so that all Canadians learn about Indigenous Peoples and how they have been treated since colonization.

Recommendations

‘Reconciliation requires political will, joint leadership, trust building, accountability, and transparency, as well as a substantial investment of resources.’ – Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Across the individual dialogues and breakout sessions, a number of themes emerged, some consistently across many small group discussions. These appeared to be the product or the expression of those characteristics associated with what is, for Indigenous Peoples, an inequitable, anachronistic and paternalistic relationship between them and the Crown and/or the people who work for, or represent, the Crown. In fact, overcoming these perfectly justifiable sentiments may be the greatest impediment to building trust in the government’s commitment to reconciliation and a renewed relationship with Indigenous Peoples.

However, there was also a sense of optimism that, if the government would take careful and meaningful actions now on many of the issues facing Indigenous Peoples, trust could begin to be built.

It was a very consistently expressed view among participants that the government’s actions have not kept up to its words.

The following describes some recommendations that emerged from the dialogue. Some were explicit recommendations, such as removing anachronistic and paternalistic provisions in the Indian Act that deny First Nations ready access to their own revenues, and others, such as reviewing how Canada exercises its fiduciary obligation, while not being expressly articulated by delegates, were inspired, and align with, the concerns and ideas expressed during the dialogue.

1. Adopt the 94 calls to action

By establishing a new and respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians, we will restore what must be restored, repair what must be repaired, and return what must be returned. – Commissioners of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission eloquently and powerfully documents the history of colonization in Canada and the residential school system, and provides practical calls to action in the areas of education, law, health, language, culture, and other areas that would serve to advance efforts to promote reconciliation.

The Government of Canada should take immediate steps to implement the calls to action. The government should explain and document the steps it has taken, or intends to take, to implement a readily accessible action plan that can be used as a report card to measure the government’s success of and commitment to the calls to action. This action plan should be available on the Government of Canada’s website.

2. Stop the adversarial approach

Trudeau government withdraws court case on health care for First Nations children – Toronto Star headline, Nov. 30, 2017

Participants expressed frustration that Canada continues to fight Indigenous Peoples on the recognition of their Aboriginal rights, which are already protected by Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

The Government of Canada should take immediate steps to stop the litigious and adversarial approach to Aboriginal rights, including — in the spirit of transparency and openness — by making Department of Justice legal opinions publicly available, by placing a moratorium on legal challenges to the expression of Aboriginal rights, and by engaging in nation-to-nation, Inuit-to-Canada and government-to-government dialogue and negotiation to find mutually agreeable resolutions where there are disputes.

In fact, this recommendation aligns with the remarks of Jody-Wilson Raybould, Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada:

‘The pathway to reconciliation is to establish proper relations between Indigenous Peoples and the Crown that is no longer focused on fighting about “who is an Aboriginal people” or “whether Aboriginal title and rights exist” — but rather is focused on collaboratively recognizing and implementing those rights.’ – B.C. Cabinet and First Nations Leaders’ Gathering, Vancouver, B.C., Sept. 7, 2016

3. Re-define the balance of power

Participants argued that Canada must share decision-making power with Indigenous Peoples. Today, the Government of Canada wields a disproportionate amount of control over the pace and scale of change. Further, some participants observed that Canada’s statements and actions suggest reconciliation is a two-way street — with give and take on both sides. Rather, taking a lead from restorative justice and in the spirit of rebuilding the relationship, Canada — and, importantly, as the party who committed the injustice — must acknowledge its actions, express the will to make amends and take concrete steps to redress the harm that it has caused.

4. Canada needs to be complicit

‘Let’s get this behind us. Let’s raise a generation of First Nations kids — for the first time in the history of this country — that actually get the same level of services that every other kid enjoys.’ -Cindy Blackstock, executive director, First Nations Child and Family Caring Society

Participants, including those who worked for the Government of Canada, expressed disappointment that there is a strong prevailing sense that the government or its representatives lack true empathy for making things right. Rather, participants observe a great resistance to change from the bureaucracy — which is either overwhelmed by, or even hostile to, the government’s stated agenda.

It was recommended that every federal department develop a reconciliation action plan that would articulate a framework by which each organization would support reconciliation in Canada. Such action plans would be tied to each department’s strategic plan and would state its commitment to reconciliation, describe practical actions to contribute to reconciliation, and include a reporting mechanism to measure progress toward the organization’s goals and its actions.

5. Actions speak louder than words

‘We have to deliver. The days of denial are behind us.’ – Jane Philpott, minister of Indigenous Services

Many participants expressed dismay at how little has been done and how little has changed, despite the priority the government has placed on the Indigenous agenda. While investments in housing and infrastructure have been described by the government as historic, they will not significantly address the shortfall if the government continues to fund housing and infrastructure in the same “pay-as-you-go” manner.

The government must also take immediate steps to correct the things that can be corrected. For example, one participant outlined the anachronistic and paternalistic management of Indian Moneys in the Indian Act. In 2015, over $800 million of Indian Moneys was being held in the Consolidated Revenue Fund and, based on data from 2006 to 2011, approximately $250 million of Indian Moneys is being deposited into the fund annually. To gain access to this — their own — money, First Nations must meet very strict and time-consuming procedures. A reading of the provisions of the Indian Act that permit First Nations access to these revenues are evocative of the most odious characteristics of a colonial relationship, including, perhaps most offensively, “any other purpose that in the opinion of the minister is for the benefit of the band.” This should, and can, be changed easily and quickly.

6. Get our own house in order

‘The Government of Canada recognizes that all relations with Indigenous Peoples need to be based on the recognition and implementation of their right to self-determination, including the inherent right of self-government.’ – Principles respecting the Government of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous Peoples

A number of participants also reflected on governance structures within Indigenous communities, and the lack of confidence in their own governance systems. In many cases, governance systems are not chosen by the community, but are forced upon them through the Indian Act.

Immediate steps must be taken to introduce mechanisms through which Indigenous Peoples can re-establish their own governance structures — rooted in traditional Indigenous cultural values — and rebuild their nations.